Alright, pull up a comfy chair, maybe pour yourself something thoughtful. We’re drifting just past the official turn of the millennium for this one, but Come Undone (original French title: Presque Rien, meaning "Almost Nothing") from 2000 feels spiritually connected to the raw, searching independent cinema that blossomed in the late 90s. Directed by Sébastien Lifshitz, this French drama landed just as VHS was ceding ground to DVD, but its intimate, often painful honesty feels right at home in our reflective corner of VHS Heaven. It’s the kind of film you might have stumbled upon in the ‘World Cinema’ section, drawn in by a cover hinting at intense emotion, and found yourself wrestling with long after the tape clicked off.

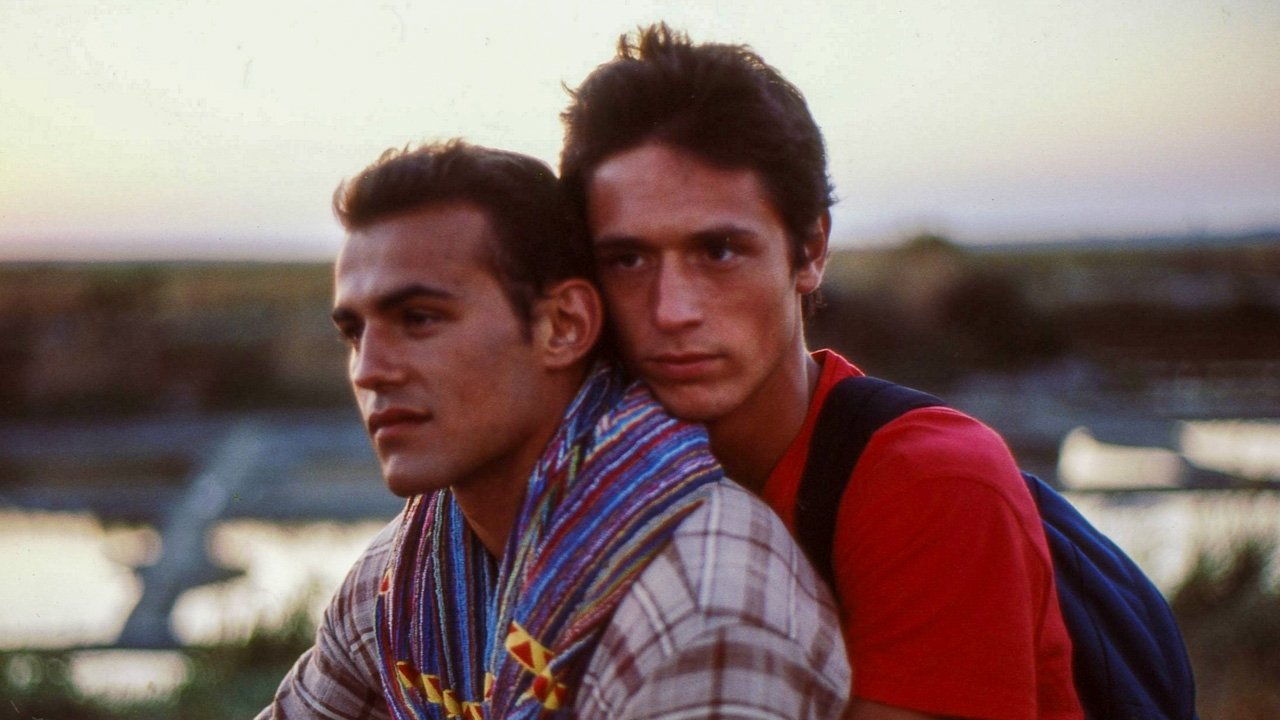

The film doesn't coddle you. It throws you immediately into a fractured timeline, mirroring the protagonist Mathieu’s shattered emotional state. We jump between a sun-drenched summer romance on the Brittany coast and the grey, oppressive aftermath back home months later. This non-linear structure isn't a gimmick; it's the very heart of the film’s power. How else to portray the way memory works when dealing with trauma and heartbreak? The vibrant, almost blinding intensity of first love – Mathieu (Jérémie Elkaïm) meeting the confident, slightly older Cédric (Stéphane Rideau) – is constantly juxtaposed with the crushing weight of its dissolution and Mathieu’s subsequent breakdown. It forces us to ask: which is the 'real' time? The intoxicating present of the past, or the desolate present of the now?

A Love Story, Unvarnished

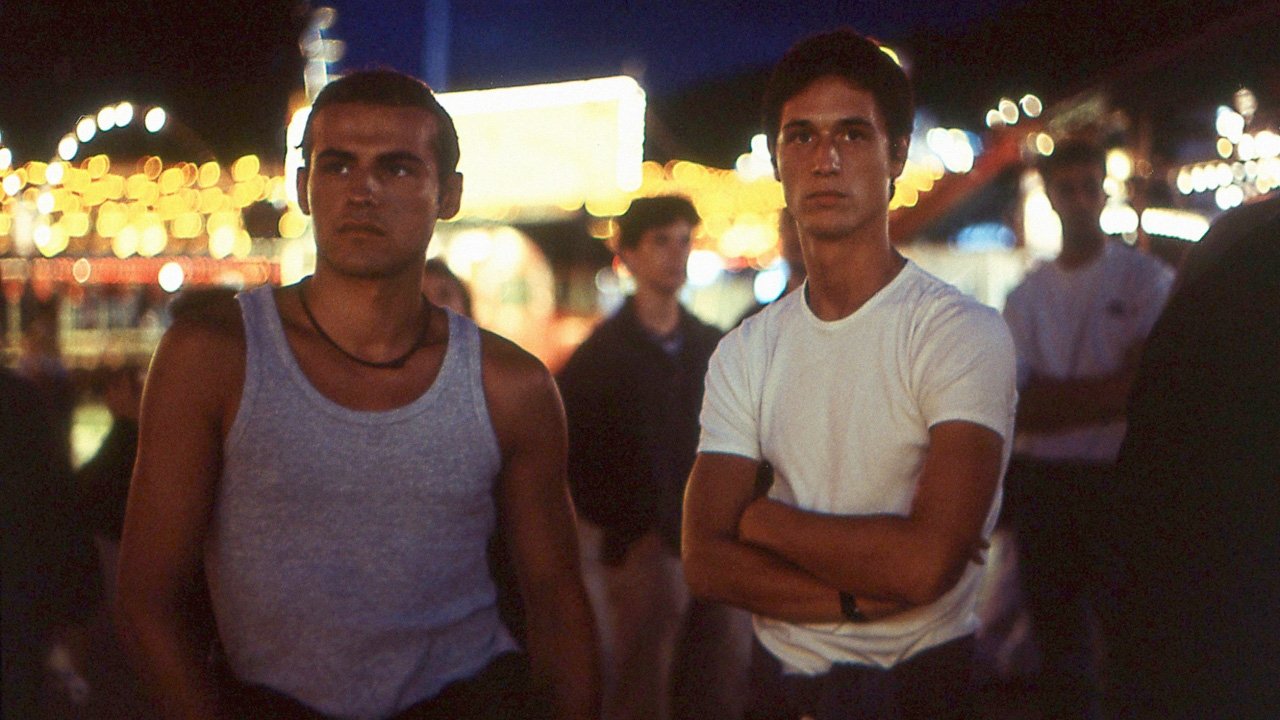

What strikes you immediately about Come Undone is its unflinching realism. Lifshitz, who co-wrote the script with Stéphane Bouquet, avoids romantic clichés. The initial courtship between Mathieu and Cédric unfolds with a nervous energy, a blend of tentative glances and burgeoning desire that feels utterly authentic. Jérémie Elkaïm, in a star-making turn, embodies Mathieu’s vulnerability with aching precision. He’s 18, discovering his sexuality, and falling headfirst into something overwhelming. Stéphane Rideau, already known to French audiences from films like André Téchiné's Wild Reeds (1994), brings a necessary charisma and subtle complexity to Cédric. He's the catalyst, the object of desire, but never just a symbol. Their physical intimacy is portrayed frankly, not exploitatively, capturing the awkwardness and intensity of young bodies exploring each other. It feels less like watching actors and more like observing real moments stolen from time.

This authenticity extends to the film's less idyllic moments. The passion inevitably gives way to tensions, misunderstandings, and the suffocating reality that summer flings often face geographical and emotional distance. There's a poignant scene involving Mathieu's mother (Dominique Reymond, delivering a beautifully understated performance), who is grappling with her own mental health struggles. Her presence adds another layer, suggesting perhaps a familial predisposition to emotional fragility, or simply the complex ways family dynamics intertwine with personal crises.

The Weight of What Remains

The fractured narrative excels in showing, not telling, the devastation of the breakup. We don't need lengthy exposition to understand Mathieu's spiral. Seeing him isolated, withdrawn, and eventually institutionalized, contrasted with the vibrant boy on the beach, speaks volumes. The stark difference in cinematography between the sun-bleached summer scenes and the muted, almost claustrophobic palette of the later timeline underscores this emotional chasm. It’s a demanding watch, certainly. There's little levity here, and the film doesn't offer easy answers or neat resolutions.

Finding solid "Retro Fun Facts" for a relatively low-budget French indie from 2000 can be tricky, but it’s worth noting the film premiered at the Berlin International Film Festival, gaining significant attention on the festival circuit which was crucial for independent films finding distribution back then. Lifshitz himself has gone on to become a celebrated documentarian, often focusing on LGBTQ+ lives (like Wild Side (2004) or Little Girl (2020)), and you can see the seeds of that empathetic, observational style here in his fiction debut. It's also interesting that Jérémie Elkaïm later co-wrote and starred in Declaration of War (2011), directed by his then-partner Valérie Donzelli, another emotionally raw French film dealing with personal crisis, suggesting a career drawn to these challenging, truthful stories. Come Undone was filmed primarily in Le Croisic, Loire-Atlantique, and the specificity of that coastal setting becomes almost another character – the sand, the sea, the summer light holding both the promise of escape and the memory of pain.

Why It Lingers

So, why revisit a film like Come Undone? Because it captures something essential about the intensity of first love and the profound disorientation of heartbreak. It’s a reminder of how formative those early relationships can be, how they can shape us, and sometimes, temporarily break us. The film’s bravery lies in its willingness to sit with discomfort, to portray mental struggle without melodrama, and to trust the audience to connect the emotional dots across its fractured timeline.

Does the non-linear structure occasionally feel disorienting? Perhaps intentionally so. Does the film wallow in misery at times? Some might argue it does, but I’d counter that it earns its somber tone through the sheer honesty of its performances and direction. It’s not aiming to be uplifting; it’s aiming to be true.

Rating: 8/10

This score reflects the film's powerful, authentic performances, particularly from Elkaïm, its brave and effective use of non-linear storytelling to convey emotional trauma, and its unflinching portrayal of young love and mental fragility. It avoids easy sentimentality and achieves a raw intimacy that’s hard to shake. While its unrelenting somberness might make it a difficult watch for some, its artistic integrity and emotional honesty make it a significant work from the cusp of the new millennium, one that carries the spirit of the best 90s independent cinema.

It’s a film that doesn't just show you a story; it makes you feel the weight of its "almost nothing," which, as anyone who's loved and lost knows, can feel like everything.