There are certain films that don't just tell a story; they feel like they hold a piece of your own past, reflecting memories you didn't even know you had. Giuseppe Tornatore's Cinema Paradiso (1988) is one such film. It arrives not with a bang, but with the gentle flicker of a projector lamp, casting images of youth, love, and loss onto the screen of memory. Watching it again, perhaps decades after that first encounter on a worn VHS tape rented from a local store, feels less like revisiting a movie and more like unearthing a beautifully preserved time capsule, fragrant with the bittersweet scent of nostalgia.

Where Movies Were Magic

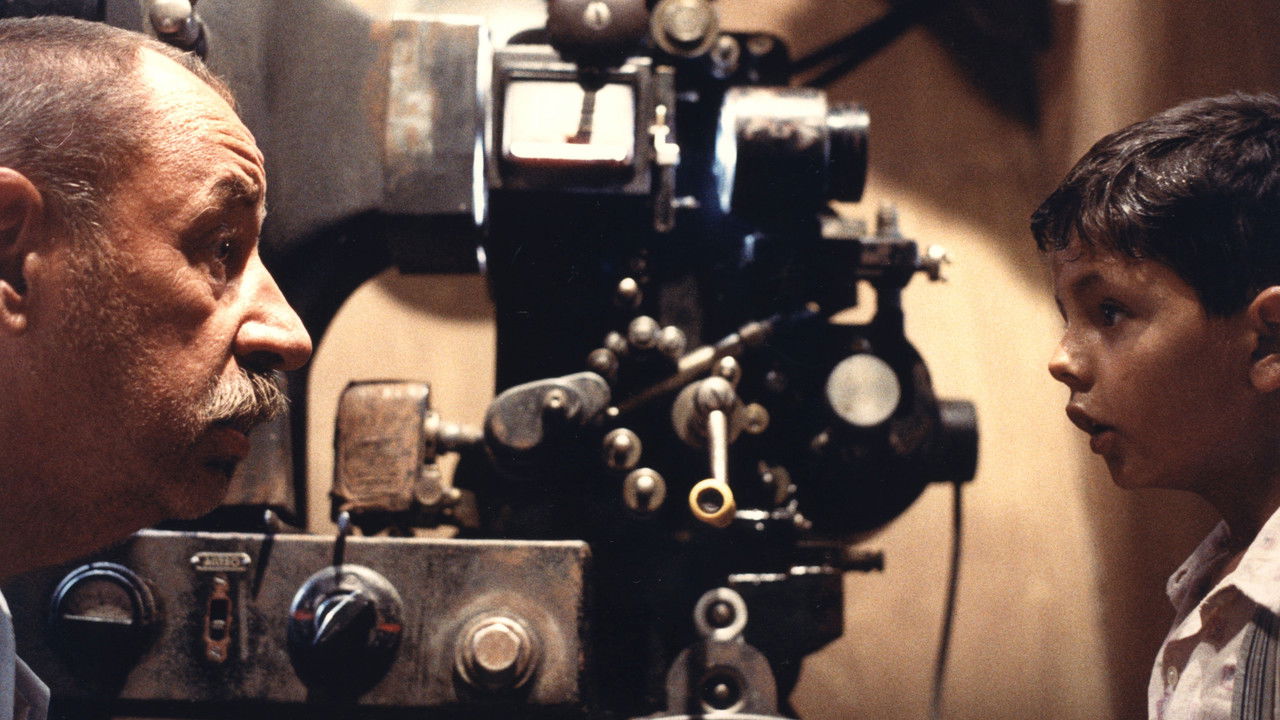

The film transports us to the small Sicilian village of Giancaldo shortly after World War II. Life revolves around the town square and, more importantly, the local movie house: the Cinema Paradiso. It's here that young Salvatore Di Vita, affectionately known as Toto (Salvatore Cascio, in a performance of astonishing naturalism for a child actor discovered locally), finds refuge and wonder. He’s utterly captivated by the moving pictures, forging an unlikely, deeply touching friendship with the cinema's projectionist, the gruff but warm-hearted Alfredo (Philippe Noiret). Their bond, built amidst the whirring projectors and stacks of flammable nitrate film, forms the undeniable soul of the story.

Tornatore, who also penned the screenplay, doesn't just depict a love for cinema; he infuses the film with it. The Paradiso isn't merely a setting; it's a character in itself – a sanctuary, a community hub, a place where dreams flicker to life in the dark. We see the shared gasps, the laughter, the tears of the audience, reminding us of a time when movie-going was perhaps a more communal, less solitary experience. Remember gathering with friends, the buzz before the lights went down in a packed theater, or even just the shared ritual of choosing that tape at the video store? Cinema Paradiso taps directly into that collective memory of cinematic magic.

Alfredo and Toto: A Legacy in Light and Shadow

The dynamic between Alfredo and Toto is rendered with such heartfelt authenticity. Philippe Noiret, a titan of French and Italian cinema (known for roles in films like Il Postino (1994)), embodies Alfredo with a perfect blend of world-weariness, paternal warmth, and quiet wisdom. He sees Toto's passion and potential, becoming mentor, friend, and surrogate father. Their interactions, from Toto’s initial mischievousness to their shared quiet moments in the projection booth, feel utterly real. Salvatore Cascio’s wide-eyed wonder as young Toto is simply captivating; it's the look of someone discovering not just movies, but life itself. As Toto grows into adolescence (Marco Leonardi) and eventually adulthood (Jacques Perrin, who starred decades earlier in another ode to youth, The Chorus (1945)), the echoes of Alfredo’s influence remain profound.

Interestingly, the film's journey to iconic status wasn't straightforward. Its initial, longer cut received a lukewarm reception in Italy. It was only after being significantly shortened for international release – trimming nearly an hour, focusing more tightly on the Toto-Alfredo relationship and Toto's later life – that it charmed the Cannes Film Festival jury (winning the Grand Prix) and eventually scooped the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film in 1989. Some argue the longer "Director's Cut," later released, offers more context, particularly regarding Toto's lost love, Elena. But there’s a purity and potency to the internationally recognized version, the one most of us likely discovered on VHS, that arguably strikes a more universal chord. It focuses the emotional impact, letting the core themes resonate without distraction.

Music, Memory, and Montage

No discussion of Cinema Paradiso is complete without mentioning the score by the legendary Ennio Morricone. It's not just background music; it's the film's heartbeat. The melodies are instantly recognizable, capable of evoking joy, melancholy, and that specific ache of remembrance with just a few notes. The score perfectly complements Tornatore's visual poetry, particularly in the sequences depicting the passage of time and the changing landscape of both the village and cinema itself.

And then there's the ending. (Minor Spoiler Alert, though it's one of cinema's most famous conclusions). The adult Salvatore, now a successful filmmaker, returns to his hometown for Alfredo's funeral and receives a final gift: a reel compiled by Alfredo containing all the kissing scenes the village priest had forced him to censor decades earlier. This montage isn't just about restored kisses; it's a flood of suppressed memories, lost innocence, and the enduring power of the cinematic moments that shape us. It’s a profoundly moving sequence, a testament to love in its many forms – romantic love, familial love, and the deep, abiding love for film itself. Does any other cinematic ending so perfectly encapsulate the bittersweet beauty of looking back?

Final Thoughts: A Timeless Treasure

Cinema Paradiso is more than just a film about movies; it’s about how art intertwines with life, how relationships shape us, and how memory sculpts our present. It captures the magic of discovery, the pain of separation, and the way certain places and people lodge themselves permanently in our hearts. Watching it feels like coming home, even if it’s to a home conjured purely from light and shadow. It’s a film that understands the unique power cinema holds – the power to transport, to connect, and to preserve moments of pure emotion.

Rating: 9.5/10

This near-perfect score reflects the film's masterful blend of heartfelt storytelling, unforgettable performances (especially from Noiret and Cascio), stunning direction, and Morricone's iconic score. The slight deduction acknowledges that some might find its sentimentality borders on saccharine at moments, or prefer the narrative breadth of the longer cut. However, the version that won hearts worldwide, the one likely gracing VHS Heaven shelves, remains an incredibly powerful and resonant piece of filmmaking. It's a film that reminds us why we fell in love with movies in the first place, leaving you with a lingering warmth and perhaps a tear in your eye, long after the credits roll. What better gift could a film give?