Here's a review for "Picnic" (1996) in the style of "VHS Heaven":

***

Imagine standing atop a high wall, the only world you know stretching out below, convinced that this narrow, precarious path is the only route to salvation before the end arrives. This stark, unforgettable image is central to Shunji Iwai's haunting 1996 film, Picnic – a piece that feels less like a narrative and more like a captured dream, or perhaps a shared delusion, found on a dusty shelf in the furthest corner of the video store. Released in Japan shortly after his breakthrough hit Love Letter (1995), Picnic (though actually filmed earlier) presents a starkly different side of Iwai, showcasing a raw, experimental energy that feels worlds away from gentle romance. It's a film that doesn't offer easy answers, choosing instead to immerse us in the fragile reality of its protagonists.

Walking the Line

The premise is deceptively simple, yet deeply unsettling. We meet Coco (Chara), Tsumuji (Tadanobu Asano), and Satoru (Koichi Hashizume), three patients confined within the stark walls of a mental asylum. Believing the world is set to end tomorrow, they embark on a final "picnic," their destination the highest point they can conceive of: the top of the very wall that encloses them. Their journey isn't one of escape in the conventional sense, but rather a strange pilgrimage along this boundary, a desperate grasp for meaning and perhaps transcendence in a world that has deemed them broken.

The atmosphere Iwai crafts is immediate and palpable. Forget glossy cinematography; much of Picnic possesses a raw, almost documentary-like texture. This wasn't just an aesthetic choice; Iwai reportedly utilized consumer-grade Hi8 video cameras for portions of the filming, lending sequences an unnerving intimacy and immediacy. Coupled with bleached-out colours, wide-angle lenses distorting the periphery, and often handheld camerawork, the visual style perfectly mirrors the characters' fractured perspectives and their profound sense of isolation, both from society and sometimes, it seems, from a shared reality.

Whispers from the Edge

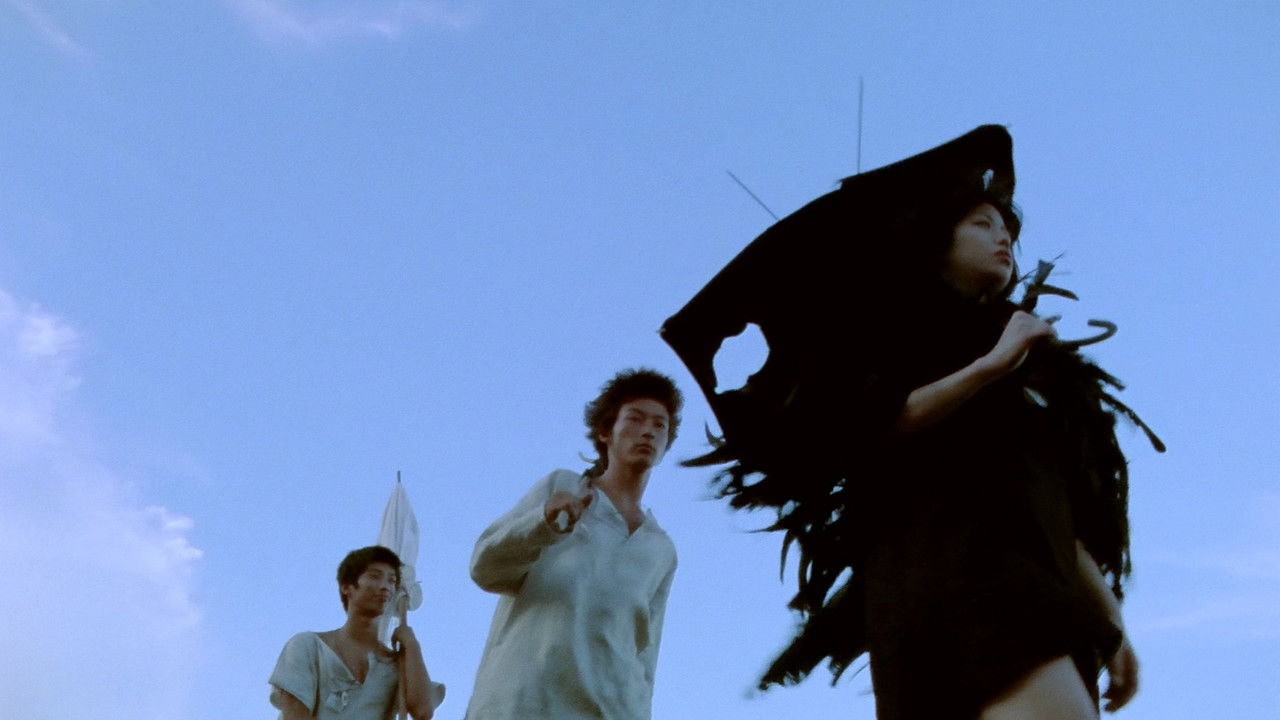

What truly anchors Picnic are the performances, particularly from Chara and Tadanobu Asano. Chara, known primarily as a unique and popular singer in Japan, brings a heartbreaking vulnerability and ethereal strangeness to Coco. Her character, adorned with black raven feathers she believes will help her fly, embodies a childlike innocence twisted by trauma. Asano, already carving out his niche as a compelling force in Japanese independent cinema (later gaining international fame in films like Ichi the Killer (2001) and Marvel's Thor series), delivers a quietly intense performance as Tsumuji, the character who tragically introduces Coco to her fate. There’s a magnetic, damaged quality to his portrayal, conveying layers of unspoken pain. Koichi Hashizume as Satoru, the most grounded yet still deeply troubled member of the trio, provides a necessary counterpoint.

These aren't characters defined by detailed backstories or clear diagnoses. Iwai, who also wrote the screenplay, trusts us to glean their inner lives from fleeting moments, gestures, and fragments of dialogue. It's a challenging approach, demanding patience and empathy, but it ultimately makes their plight feel more authentic, less like clinical case studies and more like encounters with wounded human beings adrift in a world that doesn’t understand them. Doesn't this deliberate ambiguity force us to confront our own assumptions about mental illness and societal acceptance?

A Different Kind of 90s Find

Watching Picnic today evokes a specific kind of nostalgia – not necessarily for the film itself, which likely wasn't a common rental, but for the era of discovering challenging, boundary-pushing cinema. In the mid-90s, amidst the blockbusters, finding an import VHS tape or catching a late-night broadcast of something like Picnic felt like uncovering a secret. It represents a certain strand of 90s Japanese filmmaking – fiercely independent, stylistically bold, and unafraid to tackle difficult themes with a poetic, sometimes abrasive, honesty. There’s no slick Hollywood resolution here, no easy catharsis. It’s a film that sits with you, uncomfortable but resonant. It asks profound questions about freedom – can it be found even within the strictest confines? Is their perceived reality any less valid than our own?

The film’s journey itself mirrors its content: filmed before the gentler Love Letter, its delayed release perhaps speaks to its more challenging nature. It didn’t achieve widespread recognition outside of festival circuits and dedicated cinephile circles, cementing its status as a cult piece within Iwai's diverse filmography. It’s a testament to a director exploring the edges of his craft and the human condition.

Final Verdict

Picnic is undeniably bleak, a demanding watch that offers little in the way of conventional comfort. Yet, its stark beauty, the raw authenticity of its central performances, and Shunji Iwai's distinctive, immersive direction make it a significant work. It captures a specific feeling of alienation and desperate hope with haunting precision. It's the kind of film that reminds you of the power of visual storytelling to convey complex emotional states beyond simple dialogue.

Rating: 7.5/10 - This score reflects the film's artistic merit, powerful performances, and unique vision, acknowledging that its challenging tone and deliberate ambiguity won't resonate with everyone. It's a difficult journey, but one that offers profound, if unsettling, rewards for those willing to take the walk along the wall.

What lingers most is the quiet tragedy of their picnic – a desperate reach for connection and meaning on the very structure symbolizing their confinement, under a sky indifferent to their perceived apocalypse.