The flickering static clears, and a child’s bedroom fills the screen. But this isn’t the sun-drenched suburbia of Spielberg; there’s a chill in the air, a palpable weight of grief clinging to the shadows. Something is wrong here, even before the toys start moving on their own. This is the unsettling world of Making Contact, a 1985 curiosity box that tried to tap into the E.T. zeitgeist but ended up somewhere far stranger, tinged with a distinctly European melancholy that feels miles away from Amblin.

### Echoes in the Static

Directed by a young Roland Emmerich, years before he became Hollywood's go-to guy for global destruction in films like Independence Day (1996) and The Day After Tomorrow (2004), Making Contact (originally released in Germany as Joey) feels like a different beast entirely. It follows young Joey (Joshua Morrell), reeling from the recent death of his father. He discovers he possesses telekinetic abilities, seemingly triggered by his grief, allowing him to communicate via his toy telephone with… something. Is it his father? Or something else, something sinister lurking just beyond the veil?

The film wears its influences on its sleeve – Poltergeist (1982), E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial (1982), even shades of Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977) are visible. Yet, Emmerich injects a surprising amount of emotional heft, particularly concerning Joey’s struggle with loss. Joshua Morrell carries much of the film, portraying Joey's isolation and vulnerability with a quiet intensity that resonates. His relationship with his mother, played with weary tenderness by Eva Kryll, grounds the fantastical elements in genuine human pain. This wasn't just another kids' adventure; it dared to explore darker emotional territory.

### Fletcher Knows

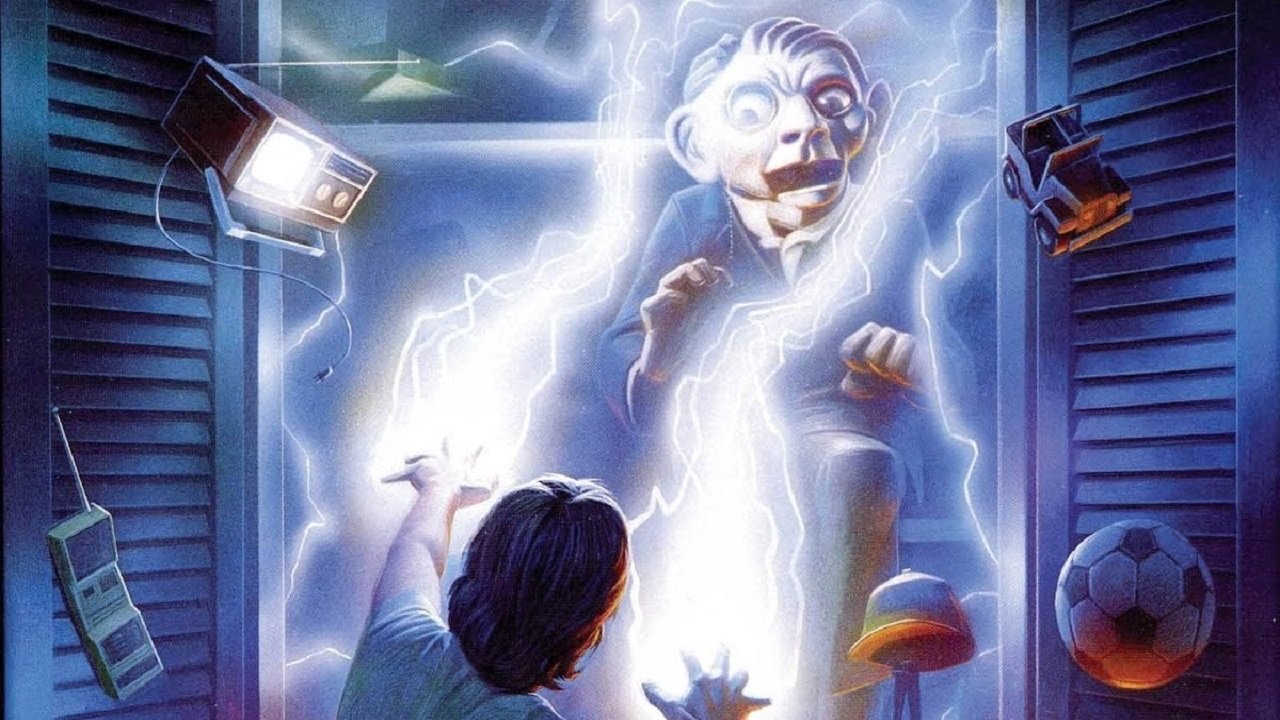

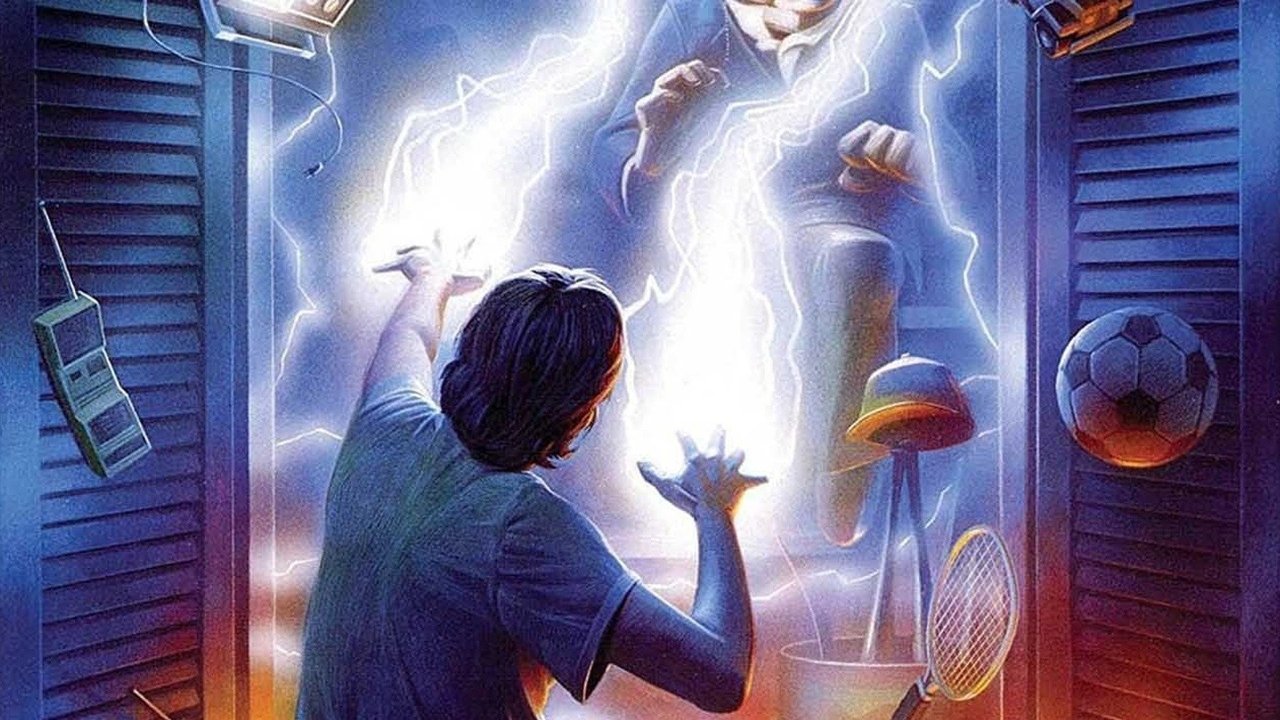

Let’s talk about Fletcher. Oh, that ventriloquist dummy. Perched menacingly in Joey's room, Fletcher becomes the focal point for much of the film's unease. Is he a conduit for the supernatural, or something more malevolent in his own right? The design itself is unnerving – less polished Hollywood prop, more uncanny valley nightmare fuel dredged up from a dusty attic. Doesn't that glassy stare still send a shiver down your spine? Emmerich uses Fletcher brilliantly, tapping into that primal fear of inanimate objects coming to life, a trope handled here with surprising creepiness for a film ostensibly aimed at a younger audience. Rumor has it that the decision to make the dummy central was partly inspired by the success of Magic (1978) and the enduring creepiness of dolls in horror.

The practical effects, while certainly products of their time, possess that tangible quality that defined the VHS era. Flying toys whiz around the room with visible wires, glowing apparitions flicker with optical printing magic, and miniature sets lend a charming, hand-crafted feel to the climactic sequences. There's an undeniable charm to seeing these effects work their magic, even if the seams show. Remember the sheer imaginative force behind seeing a kid command his toys telekinetically back then? It felt like pure wish fulfillment, albeit tinged with something eerie. The film was reportedly Emmerich’s film school graduation project, albeit one ballooned to a significant budget (around 1 million Deutsche Marks, quite substantial for a German student film at the time), allowing for this level of ambitious, if occasionally rough, effects work.

### A Transatlantic Disconnect?

One fascinating aspect is the film's journey across the pond. The version most of us likely rented from Blockbuster or Mom & Pop stores was the American cut, Making Contact, distributed by New World Pictures. This version was significantly shorter than the original German Joey cut, losing nearly 15 minutes of footage. Reports suggest these cuts aimed to streamline the plot and possibly tone down some of the darker themes or perhaps simply speed up the pacing for perceived American tastes. This might explain why the film sometimes feels disjointed or tonally uneven – we might have been watching a slightly compromised vision. It certainly contributes to the film’s cult status; tracking down the original German cut became a quest for dedicated fans seeking the full picture.

The film attempts an American setting, but the European sensibilities bleed through in the pacing, the mood, and the underlying sadness. It lacks the slick optimism often found in its American counterparts, opting instead for a more somber exploration of childhood trauma wrapped in supernatural dressing. The score, sometimes playful, often veers into genuinely haunting territory, further enhancing the unsettling atmosphere.

### The Verdict on the Line

Making Contact is a strange brew. It's undeniably a product of the mid-80s, capturing that specific blend of suburban fantasy and burgeoning technological anxiety. Yet, its willingness to engage with grief and its sometimes genuinely creepy imagery set it apart. It's flawed, certainly – the plot can meander, some effects haven't aged gracefully, and the tone sometimes wobbles between kid-friendly adventure and unsettling psychological drama. But there's an ambition here, an earnestness in its exploration of loss and the unknown, filtered through the lens of a young director finding his voice. The atmosphere is thick, Joshua Morrell's performance is affecting, and that darn dummy remains effectively chilling. It tries to be Spielberg but ends up feeling more like a melancholic European fairy tale that stumbled into an American subdivision.

Rating: 6/10

This score reflects the film's undeniable atmospheric strengths, its surprisingly potent emotional core concerning grief, and its status as a fascinating early work from a future blockbuster director. However, it's also docked points for its uneven pacing (potentially exacerbated by the US cut), dated effects (charming as they are), and a narrative that sometimes feels like it's pulling in too many directions. It’s a quintessential VHS find – imperfect, a little weird, but capable of leaving a distinct chill and a lingering sense of nostalgic unease long after the tape clicked off. It’s a call you might hesitate to answer, but one you’ll likely remember.