Okay, settle back into that worn armchair, maybe imagine the whir of a tape rewinding in the background. Let's talk about a film that might have slipped through the cracks for some, but holds a quiet charm, a sort of wistful end-of-summer feeling captured on celluloid: That Night (1992). It arrived just as the grunge era was taking hold, yet its heart beats firmly in the suburban landscape of the early 1960s, seen through the wide eyes of a child on the cusp of understanding the messy world of adults.

### Summer Nights and Suburban Secrets

What strikes you first about That Night isn't explosive drama, but atmosphere. Director Craig Bolotin, making his feature directorial debut here (he'd previously penned scripts like Black Rain (1989)), adapts Alice McDermott's well-regarded novel with a gentle hand. The film paints a picture of Levittown-esque Long Island in 1961 – manicured lawns, simmering secrets behind screened doors, and the distinct social strata of neighborhood life. We experience this world primarily through Alice Bloom (played by a remarkably young Eliza Dushku in her very first film role!), a ten-year-old girl fascinated by the rebellious, alluring older teenager across the street, Sheryl O'Connor (Juliette Lewis). Sheryl represents everything Alice isn't yet – glamorous, desired, and dangerously close to adulthood. It's a film less about plot twists and more about capturing that specific feeling of childhood observation, piecing together adult motivations from overheard whispers and stolen glances.

### Young Love and Archetypes

The central story revolves around Sheryl's forbidden romance with Rick (C. Thomas Howell), a leather-jacketed boy from the 'wrong side of the tracks'. It’s a classic setup, almost archetypal – the sensitive good girl drawn to the brooding outsider. But what elevates it beyond cliché is the raw vulnerability Juliette Lewis brings to Sheryl. Fresh off her electrifying, Oscar-nominated turn in Martin Scorsese's Cape Fear (1991), Lewis radiates a captivating mix of defiance and deep-seated insecurity. You believe her longing, her frustration with the suffocating expectations of her working-class Catholic family, particularly her weary mother (the ever-reliable Helen Shaver). C. Thomas Howell, forever etched in many of our minds from The Outsiders (1983), leans into the sensitive tough-guy persona effectively. He and Lewis share a palpable, if slightly doomed, chemistry that feels authentic to the intensity of first love. Their relationship becomes the dramatic engine, observed with a mix of fascination and burgeoning understanding by young Alice.

### Capturing a Bygone Era (Through a 90s Lens)

Filmed largely on location in Baltimore County, Maryland, the production design does a commendable job of evoking the early 60s without feeling overly staged. It's in the details – the cars, the clothes, the simmering background presence of Cold War anxieties and changing social norms. Bolotin doesn't shy away from the era's constraints, particularly the harsh judgments faced by young women like Sheryl who dared to step outside prescribed roles. There's a quiet critique here of societal hypocrisy, viewed through the innocent, yet increasingly perceptive, eyes of Alice. It's interesting to watch this 1992 film depict 1961; there's a layer of gentle nostalgia filtered through the sensibilities of the early 90s indie film scene. It lacks the cynicism that might define a similar story today, opting instead for earnestness and empathy.

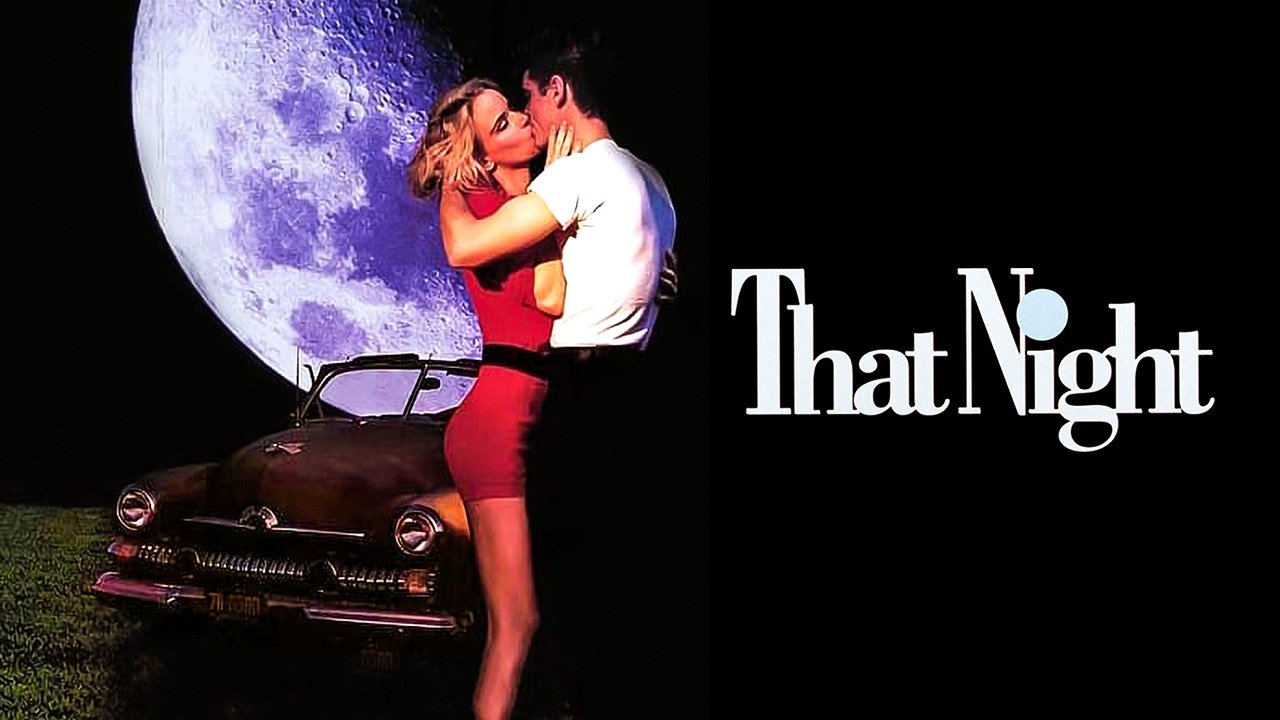

Interestingly, adapting a novel often involves streamlining. McDermott's book delves deeper into the neighborhood dynamics and Alice's internal world. While the film captures the core relationship effectively, some of that broader community texture feels a bit muted. Yet, the choice to keep Alice as the primary viewpoint character works beautifully, largely thanks to Eliza Dushku's natural performance. She provides the anchor, the relatable entry point into this very specific time and place. I remember renting this on VHS, probably drawn in by Lewis or Howell, and being surprised by its quiet intimacy and the focus on the young narrator – it wasn't quite the teen melodrama the cover art might have suggested.

### Lasting Impressions

That Night wasn't a box office smash, earning a modest $4.7 million against its budget, and critical reception at the time was generally warm but perhaps not effusive. Yet, revisiting it now, it feels like a small gem, a poignant coming-of-age story that prioritizes emotional truth over narrative fireworks. The performances, particularly from Juliette Lewis and the debuting Eliza Dushku, are the undeniable highlights. Lewis, especially, captures that potent mix of youthful rebellion and heartbreaking vulnerability that defined so many of her early roles. The film doesn't offer easy answers or tidy resolutions, mirroring the often confusing nature of growing up and witnessing the complexities of adult lives for the first time. It asks us, perhaps, to remember those moments when the world suddenly seemed bigger, more complicated, and tinged with a bittersweet understanding.

Rating: 7/10

This score reflects the film's genuine heart, strong central performances (especially Lewis), and effective period atmosphere. It successfully captures the feeling of looking back at a formative moment through a nostalgic lens. While the narrative might tread familiar ground in terms of young love archetypes, and perhaps simplifies some of the novel's depth, its emotional core remains resonant. It’s a quiet film that earns its warmth and sincerity.

Final Thought: That Night lingers like a half-remembered summer evening – maybe not the loudest or most dramatic memory, but one filled with a specific, irreplaceable feeling of youth observing the mysteries just beyond childhood's edge. A worthy discovery, or rediscovery, for the VHS shelf.