### Beneath the Cruel Surface

Some films lodge themselves in your memory not with explosions or grand pronouncements, but with a quiet, persistent ache. Nancy Savoca’s Dogfight (1991) is one such film. I remember finding the VHS box on a lower shelf at the local rental store, the cover art not quite capturing the delicate, difficult heart of the story within. It seemed unassuming, perhaps another coming-of-age tale. What unfolded on the screen, however, was something far more complex and emotionally resonant – a story that starts with an act of profound ugliness and somehow, improbably, finds grace.

### The Ugly Truth of Youth

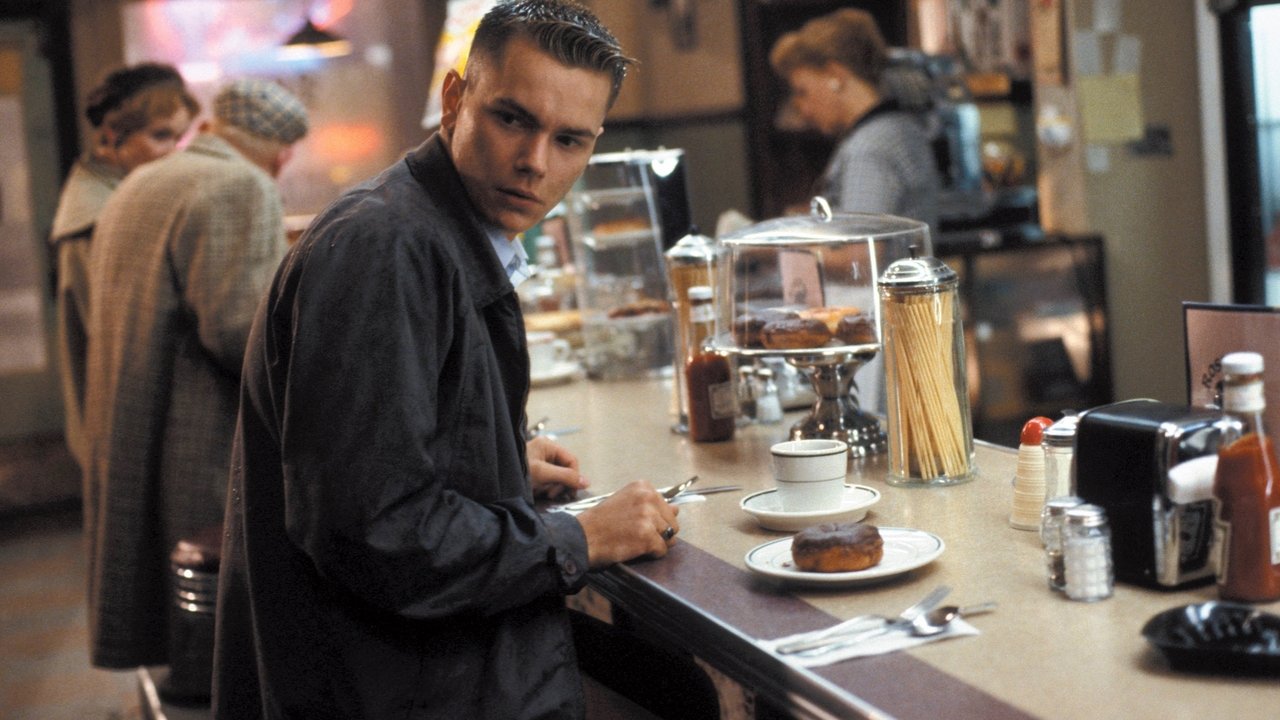

The premise itself is hard to stomach. It’s November 1963, the eve of Kennedy’s assassination and, more immediately for our protagonists, the night before a platoon of young Marines ships out to the burgeoning conflict in Vietnam. To blow off steam, they engage in a ritual known as a "dogfight": each man pools money, finds the "ugliest" date he can, and brings her to a party where a secret judge determines the "winner." It’s a concept built on casual cruelty, a display of pack mentality and toxic masculinity that feels chillingly authentic to a certain brand of youthful callousness. Our entry point is Eddie Birdlace, played with restless, simmering energy by the late, great River Phoenix. He’s cocky, trying too hard to fit in with his rowdier comrades like Berzin (Richard Panebianco), but beneath the swagger, Phoenix lets us see flickers of uncertainty.

### An Unexpected Encounter

Eddie finds his "date" in Rose Fenny, portrayed by the absolutely luminous Lili Taylor. Working in her mother’s diner, Rose is quiet, idealistic, and loves folk music. She's not conventionally glamorous by the harsh standards of the time (or the Marines), but Taylor imbues her with such earnestness, intelligence, and vulnerability that the very idea of her being subjected to the Marines' game feels unbearable. Taylor avoids every potential pitfall; Rose is never a caricature or an object of pity. She is shy but not weak, possessing a quiet dignity and a burgeoning awareness of the world's disappointments. The scenes where Eddie awkwardly convinces her to attend the party, and her hesitant excitement, are almost painful to watch, knowing the setup.

The brilliance of Dogfight, penned thoughtfully by Bob Comfort (reportedly drawing from some real-life anecdotes), is how it pivots. When Rose discovers the horrifying truth of the party, the film doesn’t shy away from her hurt or Eddie’s shame. What follows isn't a typical Hollywood redemption arc, but something more tentative and real. Stripped of his bravado, Eddie seeks Rose out, and they spend the rest of the evening together, forging a connection born from the wreckage of his cruelty. Their extended date through the streets of San Francisco (actually filmed primarily in Seattle, Washington, capturing a wonderful sense of time and place) becomes the film's soul. They talk, argue, listen to music, and slowly reveal themselves to each other. It’s in these moments that Phoenix and Taylor truly shine. Their chemistry is fragile, awkward, and utterly believable. He sees her kindness and artistic soul; she sees the scared kid beneath the Marine haircut. Savoca directs these sequences with incredible sensitivity, letting moments breathe and allowing the actors' subtle shifts in expression to carry the emotional weight. You can almost feel the chill in the night air and the warmth of their hesitant connection.

### Echoes of Innocence Lost

The backdrop of 1963 is crucial. There's an innocence hanging over the era, soon to be shattered by assassination and the escalating war in Vietnam – a conflict the film pointedly revisits in its poignant final act. The folk music Rose loves speaks to an idealism that feels increasingly fragile. The Marines' cruelty, while specific to their situation, also feels like a darker undercurrent of the era, a prelude to the disillusionment to come. Reportedly, River Phoenix deeply researched the role, interviewing Marines and striving for authenticity, capturing that blend of naive bravado and underlying fear. Lili Taylor, meanwhile, brings such genuine heart to Rose that she becomes the film's moral compass without ever feeling preachy.

Dogfight wasn't a box office smash upon release. It grossed less than $400,000 against its modest budget. Like many gems from the era, it found its devoted audience later, particularly on home video. Perhaps its quiet nature and challenging premise made it a tougher sell theatrically amidst the louder films of the early 90s. Yet, its reputation has only grown, solidifying its status as an underrated classic, sadly amplified by Phoenix's tragic death just two years later, which adds another layer of melancholy to his portrayal of youthful potential on the cusp of change. It remains one of his most nuanced and affecting performances, standing alongside work like My Own Private Idaho (1991). It’s also a testament to Nancy Savoca’s talent for capturing intimate human stories, as she did previously with True Love (1989).

### Lasting Resonance

What stays with you after watching Dogfight? It’s the performances, undoubtedly – the way Taylor’s Rose quietly refuses to be defined by others’ cruelty, the way Phoenix’s Eddie slowly sheds his hardened exterior. It’s the film's refusal to offer easy answers or a neat resolution. Can a single night of unexpected connection truly change someone? Can empathy bloom in the unlikeliest, ugliest of circumstances? The film suggests it can, but acknowledges the scars left behind. It’s a bittersweet exploration of how we hurt each other, often out of insecurity and conformity, and the small, brave moments of kindness that can push back against the tide.

Rating: 9/10

This near-perfect score is earned entirely by the film's emotional honesty, Nancy Savoca's sensitive direction, and, above all, the unforgettable, authentic performances from River Phoenix and Lili Taylor. They transform a potentially exploitative premise into a profoundly moving study of human connection, cruelty, and the fragile hope for something better. Dogfight remains a quiet powerhouse, a film whose gentle heartbreak and surprising warmth linger long after the tape stops rolling. It asks us to look beyond surfaces, both in others and in ourselves.