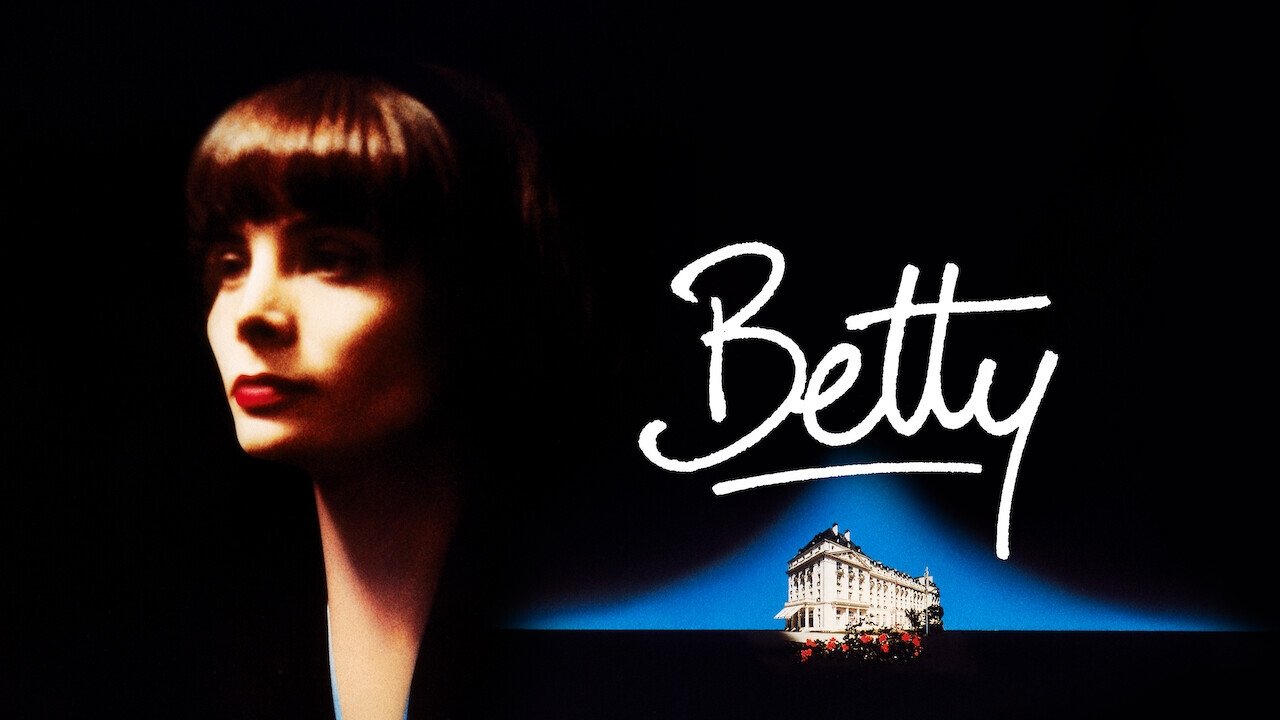

Here we go, another dive into the flickering glow of the cathode ray tube, pulling a tape from the archives that feels less like a blockbuster memory and more like a haunting echo. Tonight, it’s Claude Chabrol’s quietly devastating 1992 film, Betty. This isn't the kind of movie you'd grab for a Friday night pizza party; it's something else entirely, the sort of challenging, character-driven piece you might have stumbled upon in the ‘Foreign Films’ section of a particularly well-stocked video store, its stark cover art hinting at the psychological depths within.

A Woman Adrift

What strikes you immediately about Betty is the profound sense of dislocation. We meet the titular character, played with astonishing, fragile intensity by the late Marie Trintignant, in a haze of alcohol and despair. Found adrift in a Versailles bar, she’s picked up by an older woman, Laure (Stéphane Audran, Chabrol’s frequent collaborator and muse, exuding enigmatic warmth). Laure takes Betty back to her hotel room, offering temporary sanctuary. From this simple setup, Chabrol, adapting a novel by the master of psychological observation, Georges Simenon (Maigret series), unspools Betty’s fragmented past through a series of non-linear flashbacks. We piece together the events – a stifling upper-class marriage, perceived betrayals, a devastating act of self-sabotage – that led her to this precipice.

Chabrol's Unflinching Gaze

Claude Chabrol, often called the "French Hitchcock," was a key figure of the French New Wave, though by the 90s his style had settled into a more classical, yet no less piercing, mode. Here, he eschews flashy technique for a deliberate, observational calm that makes Betty’s inner turmoil even more potent. He doesn't judge Betty, nor does he offer easy answers. Instead, he presents her situation with a clinical, almost anthropological detachment, forcing us to confront the uncomfortable realities of her choices and the societal constraints that shaped her. The atmosphere isn't one of suspense in the traditional thriller sense, but of impending emotional implosion. There’s a quiet dread that permeates the elegantly composed shots, a sense that Betty’s trajectory, however self-inflicted, carries a grim inevitability.

It’s fascinating how Chabrol uses the setting – the anonymous luxury of hotels, the sterile comfort of bourgeois homes – to underscore Betty’s alienation. These aren't places of refuge, but gilded cages or transient spaces reflecting her internal emptiness. The production design subtly reinforces the themes; nothing feels truly lived-in or welcoming, mirroring Betty's own inability to connect or find peace.

A Towering Performance

The absolute anchor of Betty is Marie Trintignant. Watching her now, knowing her life was tragically cut short just over a decade later, lends the performance an almost unbearable poignancy. But even without that hindsight, it’s a masterpiece of contained chaos. Trintignant embodies Betty’s numbness, her desperate grabs for sensation (often through alcohol or fleeting encounters), and the flickering embers of vulnerability beneath the surface. She doesn't ask for pity; she barely seems capable of processing her own situation. It’s in the subtle shifts in her gaze, the slump of her shoulders, the moments where the carefully constructed dam of indifference threatens to break, that we see the depth of her pain. It's a performance that feels devastatingly real, avoiding histrionics in favour of a chilling authenticity. How does an actor convey such profound emptiness without losing the audience? Trintignant achieves it through sheer presence and minute, telling details.

Opposite her, Stéphane Audran is magnetic as Laure. Is she a guardian angel, a fellow lost soul, or something more ambiguous? Audran plays her with a worldly weariness and a carefully guarded warmth. The dynamic between the two women – a complex mix of maternal concern, shared disillusionment, and perhaps even a subtle rivalry – forms the film's emotional core. Their conversations, often elliptical and heavy with unspoken understanding, are mesmerizing. It's a reminder of Audran's incredible screen presence, honed over decades, often under Chabrol's direction in films like Le Boucher (1970) and Babette's Feast (1987).

Beyond the Bourgeoisie

While Chabrol frequently dissected the hypocrisies of the French middle class, Betty feels less like a social critique and more like an existential character study. It asks difficult questions about identity, self-destruction, and the possibility of redemption – or the lack thereof. Can someone truly escape their past? Can kindness heal wounds this deep? The film offers no easy platitudes. Betty’s journey, particularly its unsettling conclusion, lingers long after the credits roll. It’s a challenging watch, certainly, demanding patience and empathy from the viewer. This wasn't a film designed for mass appeal; its French release garnered critical acclaim, particularly for Trintignant, but it remained arthouse fare internationally. Finding it on VHS felt like unearthing a hidden, albeit dark, gem.

This kind of filmmaking – intimate, psychologically dense, reliant on performance and atmosphere over plot pyrotechnics – feels increasingly rare. Pulling this tape off the shelf wasn't just an act of nostalgia for the format, but for a certain kind of thoughtful, adult drama that seemed more prevalent back then.

Rating: 8.5/10

Betty is a challenging but profoundly rewarding film, anchored by an unforgettable, career-defining performance from Marie Trintignant. Chabrol’s direction is masterful in its restraint, creating an atmosphere thick with unspoken pain and existential dread. While its deliberate pace and bleak subject matter won't be for everyone, its unflinching portrayal of a woman coming apart resonates with a difficult truthfulness. The 8.5 reflects the sheer power of the central performance and Chabrol's assured handling of complex material, acknowledging that its demanding nature might not offer conventional 'enjoyment'.

It leaves you pondering the invisible scars people carry, and the often-unseen fragility lurking beneath even the most composed surfaces. A haunting piece of 90s French cinema that deserves to be remembered.