Some films arrive carrying ghosts. Not spectral apparitions, but the lingering presence of what might have been, echoes of cinematic history whispering just beneath the surface. Claude Chabrol's 1994 psychological thriller Torment (originally L'Enfer) is precisely such a film, a chilling exploration of jealousy's corrosive power that also resurrects a legendary, unfinished project from another master of French suspense. Watching it now, decades after pulling that distinctive VHS box off the "Foreign Films" shelf at the local rental store, feels less like simple nostalgia and more like confronting a beautifully crafted, deeply unsettling portrait of paradise lost.

From Sunshine to Shadow

The setup is deceptively idyllic. Paul (François Cluzet) and Nelly (Emmanuelle Béart) appear to have it all: a loving marriage, a beautiful child, and a picturesque lakeside hotel they've poured their hearts and savings into. The early scenes bask in a warm, almost dreamlike glow, capturing the simple pleasures of family life and burgeoning success. Chabrol, often called the "French Hitchcock" (though his focus was arguably more on the rot within the bourgeoisie than just suspense mechanics), masterfully establishes this sun-drenched normality, making the subsequent descent all the more jarring. It’s this stark contrast that hooks you – the insidious way doubt begins to creep into Paul's mind like a vine, slowly strangling the life out of their happiness.

A Masterclass in Devouring Obsession

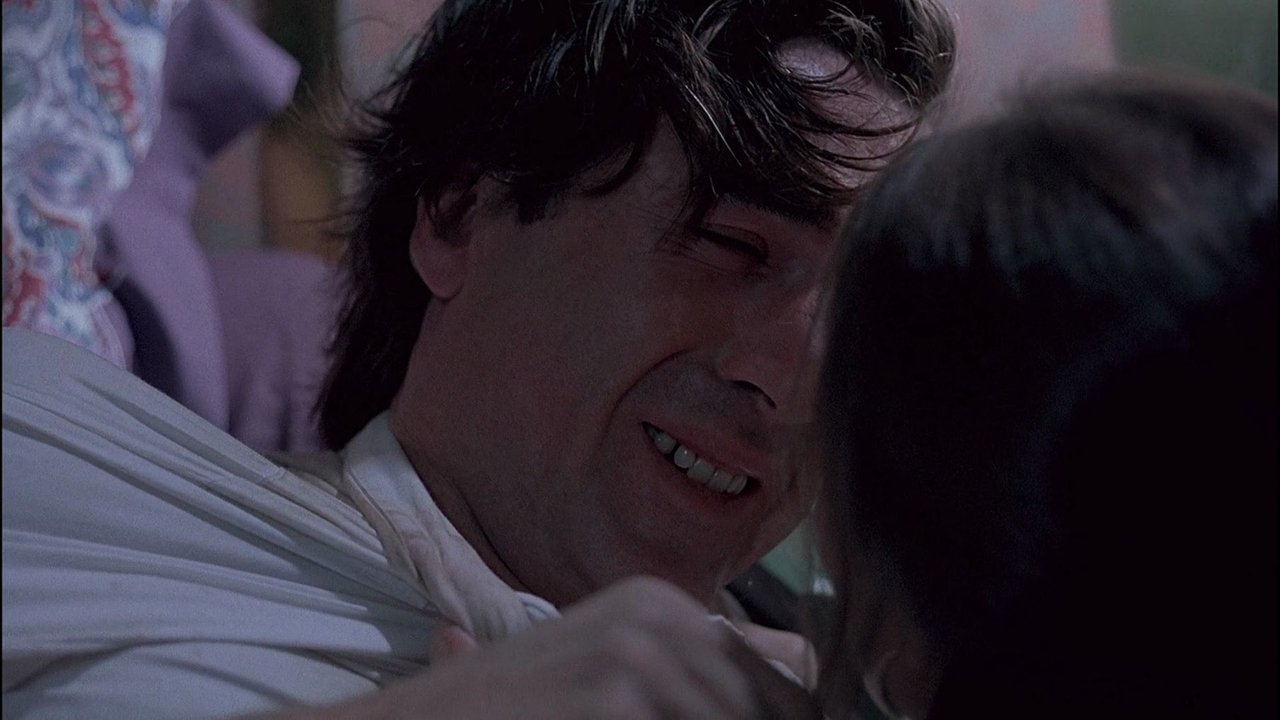

At the heart of Torment's terrifying power are the central performances. François Cluzet, perhaps best known to modern audiences for The Intouchables (2011), is simply devastating as Paul. His transformation from a happy, slightly stressed hotelier into a man consumed by paranoid jealousy is utterly convincing and deeply disturbing. It’s not a sudden snap, but a gradual poisoning. We see the suspicion flicker in his eyes during innocuous interactions, the way his interpretations twist innocent gestures into proof of infidelity. Cluzet doesn’t play Paul as a moustache-twirling villain; he portrays a man unraveling, increasingly trapped in the hell (l'enfer) of his own making. His logic becomes terrifyingly skewed, his actions escalating from invasive questions to outright psychological (and eventually physical) abuse. It’s a performance that stays with you, a raw depiction of mental disintegration.

Equally compelling is Emmanuelle Béart as Nelly. Fresh off successes like Manon des Sources (1986) and La Belle Noiseuse (1991), Béart embodies the initial radiance and subsequent bewildered suffering of a woman whose life is systematically dismantled by her husband's obsession. Her journey from playful affection to confusion, fear, and finally, a desperate attempt to understand or escape, is heartbreakingly rendered. She isn't merely a passive victim; Béart infuses Nelly with resilience and flashes of defiance, but ultimately portrays the crushing weight of being trapped in someone else's nightmare. The chemistry between Cluzet and Béart shifts from tender to toxic, forming the agonizing core of the film.

Resurrecting a Lost Vision

Now, for that fascinating piece of cinematic history – the "Retro Fun Fact" that elevates Torment beyond just another thriller. The script was originally written and partially shot in 1964 by the legendary Henri-Georges Clouzot, director of masterpieces like Les Diaboliques (1955) and The Wages of Fear (1953). Clouzot’s L'Enfer was envisioned as a wildly ambitious, experimental film exploring jealousy through subjective, almost psychedelic visuals, starring Romy Schneider and Serge Reggiani. However, the production was plagued by disasters: Reggiani fell ill, the budget spiraled, and Clouzot himself suffered a heart attack, forcing the project's abandonment. It became one of cinema's most famous unfinished films.

Decades later, Claude Chabrol took Clouzot's dense, detailed script (reportedly leaving much of the dialogue intact) and adapted it through his own lens. While Chabrol discarded Clouzot’s planned visual pyrotechnics (some tantalizing glimpses of which can be seen in the 2009 documentary Henri-Georges Clouzot's Inferno), he retained the script's relentless focus on Paul's deteriorating psyche. Chabrol's direction is more classically controlled, using precise framing and a creeping sense of claustrophobia within the hotel walls to build tension. He turns the idyllic setting sour, the shimmering lake reflecting not beauty, but Paul's distorted perceptions. Knowing this backstory adds a layer of poignant "what if" but also highlights Chabrol's skill in realizing this potent story in his own distinctive style. He honoured Clouzot's narrative core while making the film unmistakably his own.

The Unshakeable Grip of Jealousy

What makes Torment so effective, and perhaps why it lingered after that first VHS viewing, is its unwavering focus. It doesn’t offer easy answers or relief. It plunges the viewer directly into the suffocating reality of obsessive jealousy, forcing us to witness its destructive capacity. Is Nelly actually unfaithful? The film cleverly keeps us guessing alongside Paul initially, but it swiftly becomes clear that the objective truth barely matters. Paul’s perception is his reality, a prison built from suspicion and insecurity. Doesn't this unflinching look at how internal demons can warp reality feel disturbingly relevant, even today? The film asks profound questions about trust, perception, and the fragility of happiness.

Final Thoughts

Torment isn't a comfortable watch. It's a meticulously crafted, superbly acted descent into madness, powered by François Cluzet's terrifyingly committed performance and Emmanuelle Béart's palpable vulnerability. Claude Chabrol directs with chilling precision, honoring the ghost of Henri-Georges Clouzot's lost project while delivering a potent psychological thriller in its own right. It might lack the overt stylistic flourishes Clouzot envisioned, but its psychological intensity is undeniable. It’s the kind of film that might have felt particularly stark viewed on a flickering CRT, the darkness in Paul’s mind seeming to bleed into the shadows of your living room.

Rating: 8/10 - This score reflects the film's powerful performances, masterful direction, and unflinching exploration of its central theme. It’s a near-perfect execution of a psychological nightmare, perhaps only held back from a higher score by its sheer, unrelenting bleakness, which might prove too much for some viewers.

Torment remains a potent reminder of how easily the foundations of love and trust can crumble under the weight of internal demons, leaving you to ponder the terrifyingly thin line between love and possession long after the tape stops rolling.