Some films wrap you in a comforting embrace, others thrill you with spectacle. And then there are films like David Mamet’s 1994 adaptation of his own incendiary play, Oleanna. Watching it feels less like settling in for a movie night and more like being locked in a small, airless room where the tension steadily escalates until you can barely breathe. It doesn't offer catharsis; it offers confrontation, leaving you grappling with its unpleasant truths long after the credits roll. This wasn’t a tape you’d grab for a casual Friday night rental back in the day; this was the one you picked when you were ready for an argument – possibly with yourself.

A Collision Course in Academia

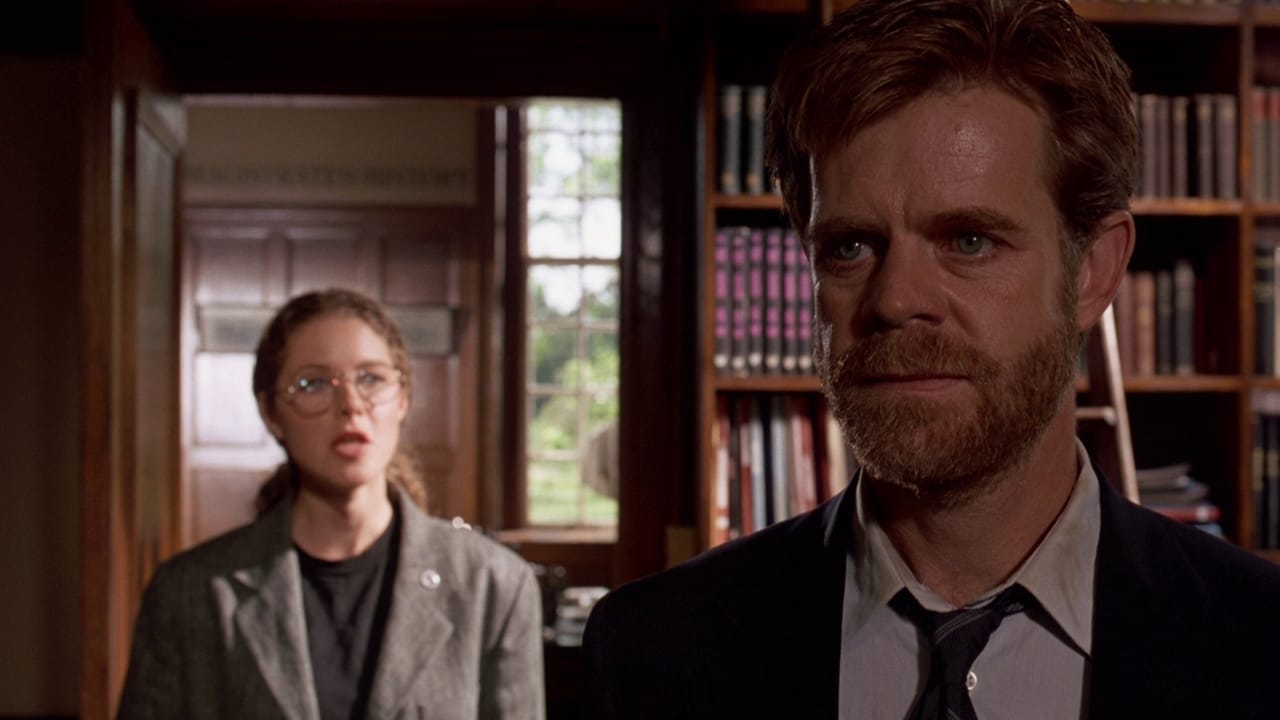

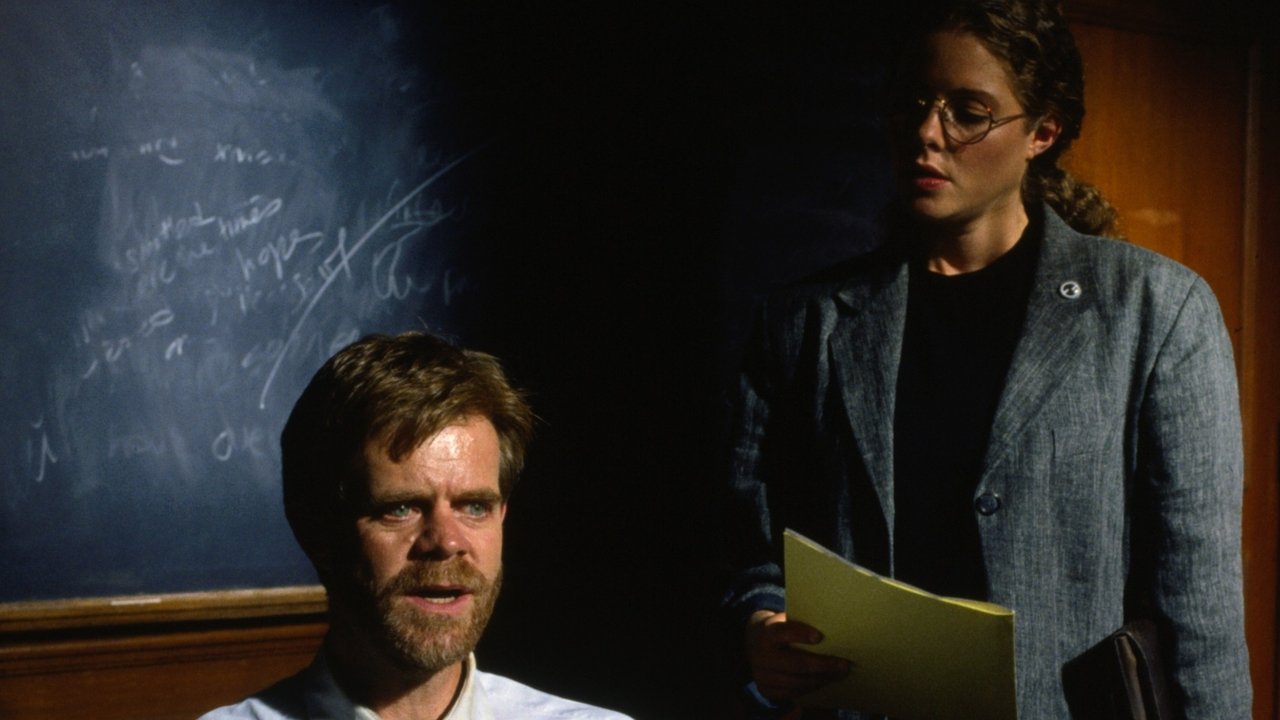

The setup is deceptively simple: Carol (Debra Eisenstadt), a struggling university student, visits her professor, John (William H. Macy), during office hours. She’s failing his course, doesn’t understand his dense theoretical framework, and fears the impact on her future. He, initially distracted by phone calls about closing on a new house – a symbol of his impending tenure and established security – gradually shifts from paternalistic condescension to attempts at connection, offering unorthodox help and sharing personal anxieties. What unfolds across three distinct acts, primarily confined to John’s office, is a harrowing power struggle fueled by miscommunication, perceived slights, shifting ideologies, and the dangerous ambiguity of language itself.

The Mamet Cauldron

Anyone familiar with David Mamet’s work, perhaps from powerhouse dramas like Glengarry Glen Ross, knows his unique linguistic signature. "Mamet-speak" is weaponized here – clipped, repetitive, interrupted phrases where pauses and stumbles carry as much weight as the words spoken. Oleanna the play had already ignited fierce debate upon its 1992 premiere, with audiences reportedly arguing loudly during intermissions and even walking out. Mamet, fiercely protective of his vision, chose to direct the film adaptation himself, ensuring its claustrophobic intensity remained intact. He employed long takes and minimal camera movement, forcing the audience to lean into the performances, trapping us within the escalating conflict just as the characters are trapped by their differing interpretations of events.

It’s a fascinating choice, translating stage intensity directly to screen. There’s little cinematic flourish; the power resides almost entirely in the dialogue and the actors navigating its treacherous currents. For some, this might feel static, but it undeniably amplifies the raw, uncomfortable intimacy of the confrontation. Adding another layer of subtle commentary, the title "Oleanna" itself derives from a 19th-century folk song about a failed, ironically idealized utopian settlement in America. It's a hint, perhaps, at the destructive potential hidden within seemingly progressive ideals or the impossibility of perfect communication and understanding.

Two Sides of a Chasm

The film lives or dies on its two central performances, and both actors are riveting. William H. Macy, who had originated the role of John in the play's Off-Broadway run, is masterful. He charts John’s devolution from a man comfortable in his intellectual authority – albeit prone to self-important pronouncements and casual boundary-crossing – to someone utterly bewildered and enraged as his world collapses. Macy makes John’s intellectual vanity palpable, but also his moments of genuine, if clumsy, attempts to reach Carol, making his downfall all the more complex. You see the privilege, the assumptions, but also the dawning horror as his words and actions are reframed against him.

Debra Eisenstadt, specifically cast for the film (replacing Mamet’s wife, Rebecca Pidgeon, who originated the stage role), brings a different, perhaps more inscrutable energy to Carol. Initially appearing uncertain and almost pleading, she transforms into an instrument of a formal complaint, embodying a rigid ideological stance. Eisenstadt skillfully portrays Carol’s growing confidence, or perhaps her hardening certainty, as she gains institutional power through the tenure committee complaint. Is she an opportunist weaponizing academic grievance? A genuinely aggrieved student finding her voice? Or something more complex, perhaps a victim of John's unintentional condescension and confusing signals, now swept up in a system eager to find fault? The film refuses to say, and Eisenstadt’s performance maintains that crucial, unsettling ambiguity. It's a stark contrast to Macy's more legible emotional unraveling.

The Weight of Silence and Interpretation

There’s a notable lack of a traditional score driving the emotion. Much of the film relies on the rhythm of the dialogue and the charged silences between words. This choice further underscores the focus on language – its power to build connection, but also its potential to wound, obfuscate, and destroy. What does John mean when he puts his arm around Carol? What does Carol hear when he dismisses the educational system? The film relentlessly forces us to question intent versus impact, objective reality versus subjective experience. It dares the viewer to pick a side, knowing full well that any definitive stance ignores crucial nuances presented by the other perspective.

This deliberate ambiguity was, of course, Mamet’s intent. He wasn't interested in crafting a simple story of victim and perpetrator, but in exploring the messy, dangerous territory where power, gender, communication, and ideology collide. It’s a film designed to provoke, to make you uncomfortable with easy answers. How much responsibility does John bear for his casual exercise of power and his often pompous language? How much does Carol bear for her interpretation and subsequent actions, seemingly driven by an unseen group?

Still Resonating, Still Uncomfortable

Decades later, Oleanna feels startlingly relevant. The debates surrounding campus culture, political correctness, the nuances of consent, and the very nature of communication breakdown haven't vanished; if anything, they've intensified and fragmented further in the digital age. Watching it now, one might ask: has our ability to navigate these complex disagreements improved, or have the lines become even more rigidly drawn? Does the film’s power struggle feel like a historical artifact, or a chillingly familiar dynamic? It remains a potent, if deeply uncomfortable, cinematic Rorschach test.

Rating: 7/10

Oleanna is undeniably powerful filmmaking, anchored by two exceptional performances and Mamet’s confrontational script. Its deliberate ambiguity and stage-bound feel are both its greatest strength and its potential limitation for viewers seeking clearer resolutions or more cinematic dynamism. The score reflects its effectiveness as a provocative piece of drama and a showcase for its actors, while acknowledging that its refusal to offer comfort or easy answers makes it a challenging, sometimes alienating, experience. It succeeds utterly in what it sets out to do: force reflection on uncomfortable questions.

It’s a film that doesn't just play out on screen; it continues the argument in your head long after the tape has been ejected, a stark reminder of how easily words can become weapons in the wrong hands or ears.