There's a peculiar kind of intimacy in witnessing profound loss, a strange closeness forged in the sterile aftermath of disaster. It’s this unsettling space that Atom Egoyan’s 1991 film, The Adjuster, invites us into, primarily through the eyes of Noah Render (Elias Koteas), an insurance adjuster whose job places him at the epicentre of other people's fractured lives. Watching it again, years after pulling that distinctive VHS tape off the shelf – probably nestled somewhere between the mainstream dramas and the slightly more adventurous 'Independent' section – the film's quiet chill and observational detachment feel even more pronounced, a haunting reflection on empathy, voyeurism, and the ways we cope (or fail to cope) with the void.

After the Fire

Noah doesn't just assess damages; he steps into the vacuum left by catastrophe, offering solace, practical help, and temporary lodging in a bland, anonymous motel owned by his company. He's a comforting presence, almost saintly in his calm efficiency, guiding shell-shocked clients through the wreckage of their former existences. Yet, there's an unnerving blankness behind his solicitous eyes. Is he a compassionate helper, or someone who derives a unique, perhaps unconscious, satisfaction from proximity to trauma? Elias Koteas delivers a masterclass in contained ambiguity here. His Noah is soft-spoken, gentle, yet carries an undeniable aura of disconnection, a man defined entirely by the needs and losses of others, seemingly devoid of a solid core himself. It’s a performance built on unsettling stillness, making Noah both sympathetic and deeply suspect.

Parallel to Noah's journey is that of his wife, Hera (Arsinée Khanjian, Egoyan’s spouse and frequent, invaluable collaborator). Hera works for the Ontario Board of Censors, spending her days in darkened rooms meticulously reviewing pornographic films, cataloguing specific acts with detached precision. Her professional voyeurism mirrors Noah’s, albeit through a different lens. She seeks transgressive moments, not for titillation, but perhaps as a way to map the boundaries of human experience, or maybe just to feel something through the mediated intensity onscreen. Khanjian portrays Hera with a quiet intensity, her isolation palpable even when surrounded by colleagues or attempting connection with Noah. Their shared home, stark and modern, feels less like a sanctuary and more like another liminal space, much like the motel rooms Noah populates.

The Egoyan Gaze

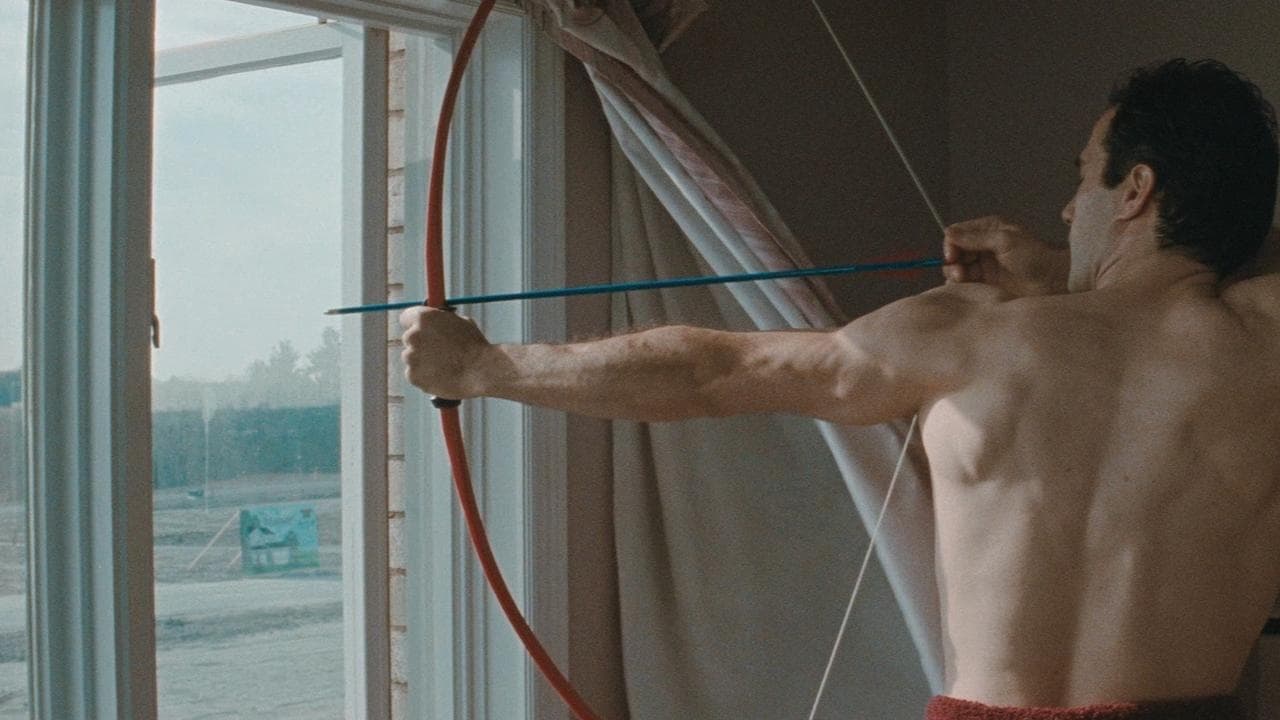

This film is pure, uncut Atom Egoyan, showcasing the thematic preoccupations and stylistic signatures that would define his work through the 90s, leading to acclaimed films like Exotica (1994) and the heart-wrenching The Sweet Hereafter (1997). His direction here is meticulous, almost clinical. The camera often observes from a distance, framing characters within architectural spaces – doorways, windows, the antiseptic corridors of the motel – emphasizing their isolation. Video technology itself plays a key role, not just in Hera’s job but also hinted at in Noah’s interactions, reinforcing the themes of surveillance and mediated reality that run through Egoyan’s oeuvre. The pacing is deliberate, allowing atmosphere and unspoken tension to build, demanding the viewer’s patience and attention. It’s a style that might have felt challenging sandwiched between more conventional rentals back in the day, but its power lies in its immersive, almost hypnotic quality.

Adding another layer of calculated strangeness is the subplot involving Bubba (Maury Chaykin) and Mimi (Gabrielle Rose), a wealthy, eccentric couple who wish to use Noah and Hera's sparsely furnished house as a film set for their own peculiar fantasies. Chaykin, always a magnetic screen presence, imbues Bubba with a mix of infantile entitlement and underlying menace. Their intrusion into Noah and Hera's already fragile domesticity serves to further blur the lines between reality, performance, and exploitation, pushing the central themes into even more uncomfortable territory. It's a bizarre, almost theatrical element that underscores the performative nature of identity and desire running through the film.

Retro Fun Facts: Adjusting the Details

- The Adjuster was a significant film for Atom Egoyan, further establishing him as a major voice in Canadian cinema and internationally. It premiered in the Un Certain Regard section at the 1991 Cannes Film Festival, cementing his art-house credentials.

- Shot primarily in and around Toronto (including locations like Scarborough), the film makes potent use of its mundane settings – the nondescript motel, the sprawling, empty-feeling house – turning everyday architecture into spaces freighted with existential unease.

- Reportedly made on a modest budget of around $1.6 million Canadian dollars, the film showcases Egoyan's ability to create a distinct, high-concept world through careful aesthetic choices rather than expensive spectacle. It’s a testament to focused, intelligent low-budget filmmaking.

- The film continues Egoyan's exploration of themes like alienation, technology's role in human connection (or lack thereof), and the complexities of grief – ideas he consistently revisited, often with Arsinée Khanjian delivering nuanced performances at the core.

Lingering Questions in the Static

Watching The Adjuster on VHS back then, the slightly degraded image quality, the hum of the VCR – it almost felt like an extension of the film's themes. You were peering into these fractured lives through yet another mediating screen. What lingers most powerfully now is the film's refusal of easy answers. What truly motivates Noah? Is Hera's censorship work a shield or a symptom? Can genuine connection arise from curated proximity to suffering? Egoyan doesn't offer clear resolutions, instead leaving us adrift in the same ambiguous emotional landscape as his characters. It’s a film that poses uncomfortable questions about empathy itself – where does compassion end and morbid curiosity, or even exploitation, begin?

It challenges the viewer, asking us to sit with discomfort and observe the quiet desperation beneath seemingly placid surfaces. It's not a film that shouts; it whispers unsettling truths about the ways we navigate loss and loneliness in a world increasingly mediated and disconnected.

Rating: 8/10

The Adjuster earns its high marks for its distinctive artistic vision, unsettling atmosphere, and deeply intelligent exploration of complex themes. The performances, particularly from Koteas and Khanjian, are perfectly modulated and profoundly affecting in their restraint. It’s a quintessential Atom Egoyan piece – challenging, hypnotic, and meticulously crafted. While its deliberate pace and ambiguous nature might not resonate with everyone seeking straightforward entertainment, for those willing to engage with its quiet intensity, it offers a rich and thought-provoking experience that stays with you long after the tape stops rolling.

It’s a stark reminder that sometimes the most profound damage isn't visible in the charred remains of a house, but hidden deep within the quiet spaces between people.