There's a certain kind of grey that settles over some films from the 80s, particularly those from Britain. Not the neon glow of a blockbuster arcade, but the damp, pervasive grey of council estates under perpetually overcast skies. Rita, Sue and Bob Too (1987) lives in that grey, yet it bursts with a defiant, often uncomfortable, technicolor energy that still jolts you decades later. Watching it again now, it feels less like a simple movie and more like a raw slice of social history captured on celluloid, smuggled onto the shelves of the local video shop between the action heroes and teen comedies.

More Than Just Mischief on the Moors

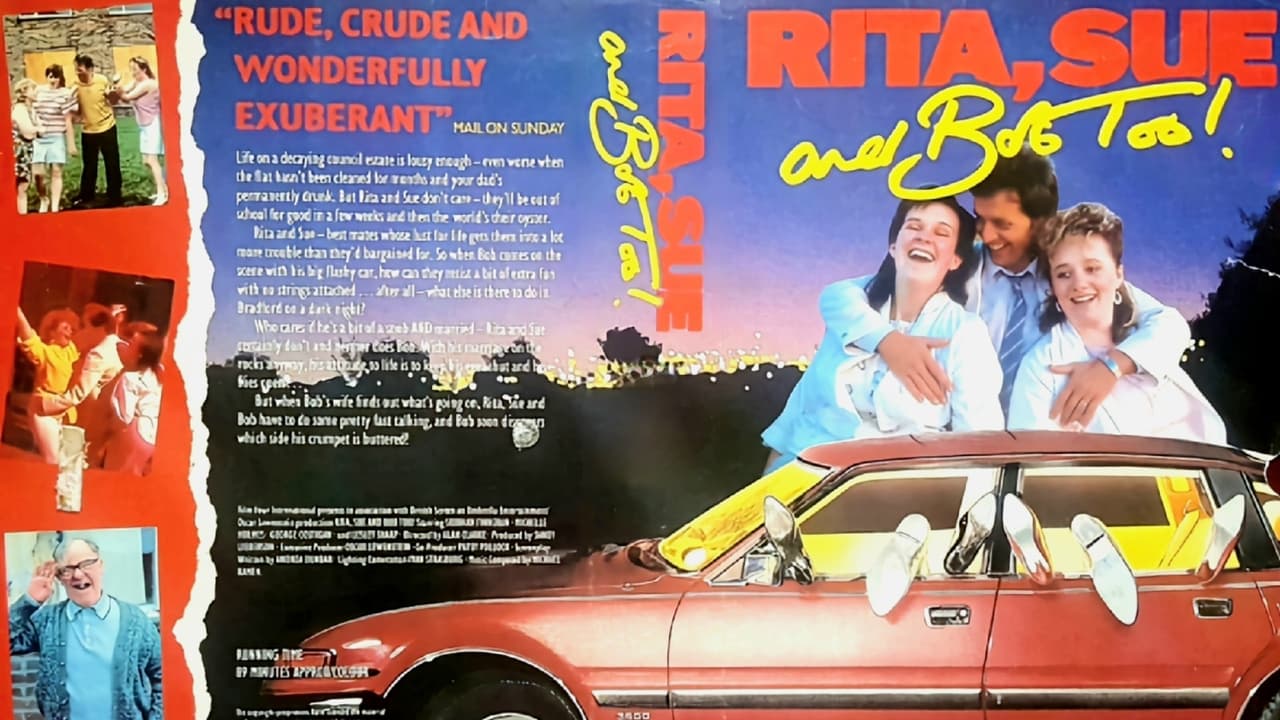

The premise, famously, is provocative: two teenage schoolgirls, Rita (Siobhan Finneran) and Sue (Michelle Holmes), living on the rundown Buttershaw estate in Bradford, begin a casual sexual relationship with Bob (George Costigan), the older, married man they babysit for. What unfolds isn't a cautionary tale in the conventional sense, nor is it a simple exploitation flick. Instead, directed by the unflinching Alan Clarke – a filmmaker never afraid to stare into the harsher corners of British life, as seen in works like Scum (1979) or Made in Britain (1982) – the film offers a portrait of lives lived with limited options, where moments of pleasure, however illicit or morally questionable, are snatched with a pragmatic, almost cheerful desperation.

The power originates from the source: the screenplay by Andrea Dunbar, adapted from her own plays. Dunbar grew up on the very Buttershaw estate depicted, and her voice rings with an almost brutal authenticity. There's no filter, no softened edges. The dialogue is coarse, funny, shocking, and utterly believable. It's reported Dunbar was initially unhappy with the film, feeling it played up the comedy over the grim reality she experienced, a tension that certainly exists within the viewing experience itself. Does the film sometimes risk making light of a deeply problematic situation? Perhaps. But that frankness, that refusal to judge or sentimentalize, is also its enduring strength.

Lightning in a Bottle Performances

What truly elevates Rita, Sue and Bob Too beyond its potentially grim subject matter are the astonishingly naturalistic performances from its young leads. Siobhan Finneran and Michelle Holmes, both teenagers making their feature film debuts, are simply electric. They capture the specific energy of adolescent girls on the cusp – the boredom, the bravado, the burgeoning sexuality mixed with a naive vulnerability. Their friendship feels lived-in, their banter sharp and real. You believe entirely in their shared world, their coded language, their defiant laughter against the bleak backdrop. Their rendition of "Gang Bang" by Black Lace during the opening credits, driving across the moors with Bob, remains an iconic, jarringly upbeat introduction to the complex dynamics ahead.

George Costigan as Bob is equally compelling, though deeply unsettling. He’s not a straightforward villain. There’s a pathetic quality beneath his swagger, a man seeking escape from his own dissatisfying life through the thrill of the illicit and the power imbalance. Costigan plays him with a certain undeniable charm initially, which makes his casual exploitation all the more insidious. His interactions with his sharp-tongued wife, Michelle (played brilliantly by Lesley Sharp, also making a strong early impression), provide some of the film's most darkly comic and revealing moments about fractured domesticity.

A Window onto Thatcher's Britain

Filmed on location, the Buttershaw estate isn't just a backdrop; it's woven into the fabric of the story. The rows of identical houses, the windswept open spaces, the palpable sense of economic stagnation – it all speaks volumes about the social conditions of Northern England in the mid-1980s under Thatcherism. This wasn't the glossy image of the decade often sold; this was the reality for communities grappling with unemployment and limited horizons. The film doesn't lecture; it simply presents this environment as the characters' unescapable reality, shaping their choices and attitudes. The fact that Andrea Dunbar drew so heavily on her own life experiences here lends the film an undeniable weight, a sense of witnessing something real, however uncomfortable. Tragically, Dunbar passed away only three years after the film's release, aged just 29, making her sharp, witty, and challenging voice feel even more precious.

The production itself wasn't without controversy. Funded by Channel 4 as part of its influential 'Film on Four' strand, its frank depiction of underage sex and working-class life caused considerable debate upon release. Some critics lauded its realism, while others condemned it as irresponsible or exploitative. Watching it today, the shock might be less acute, but the questions it raises about consent, class, opportunity, and morality remain potent. It’s a film that refuses easy answers, forcing the viewer to confront the uncomfortable ambiguities of its characters' lives.

The Verdict

Rita, Sue and Bob Too isn't always an easy watch. It's rough around the edges, morally complex, and steeped in a specific time and place that feels both distant and disturbingly relevant. Yet, it possesses a raw vitality, fueled by Andrea Dunbar's fiercely authentic writing and the unforgettable performances of its cast, particularly the young leads. It captures a facet of 80s Britain often ignored by mainstream cinema, doing so with a darkly comic energy and an unflinching gaze that stays with you. It’s a vital piece of British social realism, a controversial snapshot that sparked debate then and continues to provoke thought now. It certainly earned its place as a talked-about tape on the rental shelves.

Rating: 8/10

This score reflects the film's significant cultural impact, its powerful and authentic performances, and its brave, unflinching portrayal of a challenging subject and social environment. While its tone can sometimes feel jarring and its subject matter inherently uncomfortable, its importance as a piece of British social realist cinema, driven by Andrea Dunbar's unique voice and Alan Clarke's uncompromising direction, is undeniable. It remains a potent, provocative watch, far removed from cosy nostalgia but essential for understanding the complexities beneath the surface of the era. What lingers most isn't judgment, but the haunting echo of laughter in bleak circumstances.