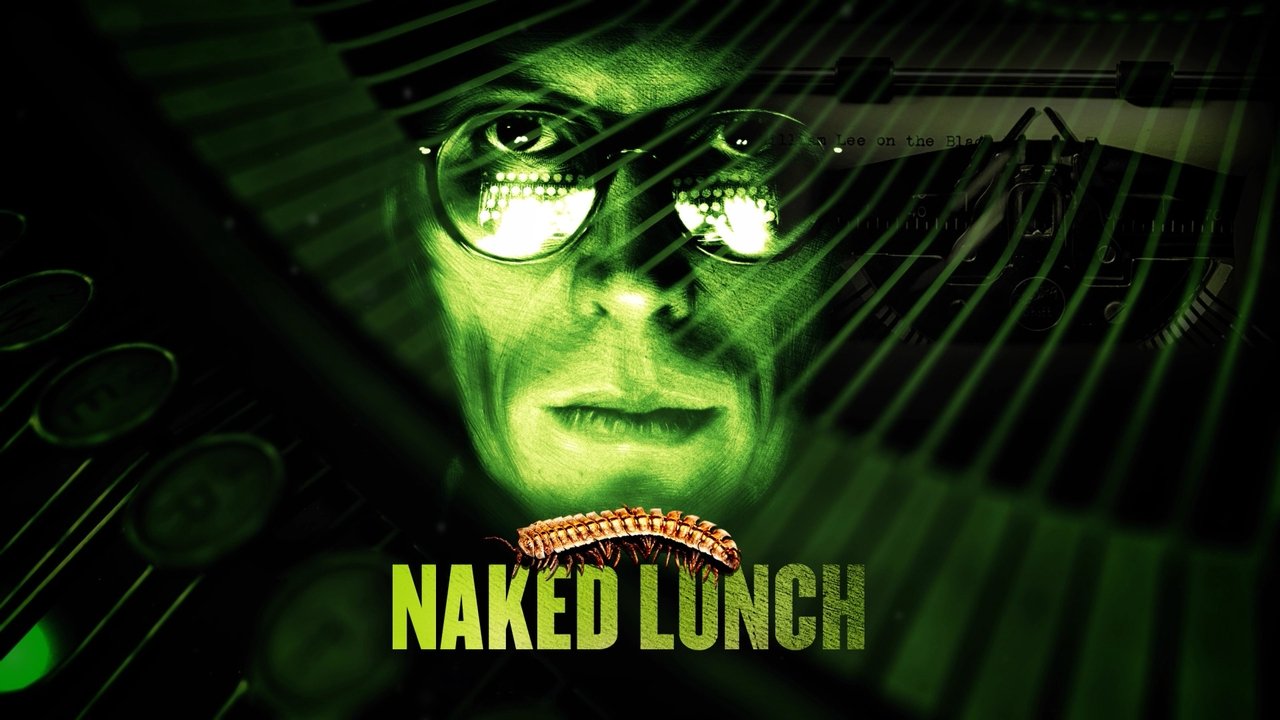

Okay, settle in. Forget the neon glow of the arcade or the easy comfort of a John Hughes flick tonight. We're cracking open a different kind of case, one stained with ink and something far more viscous. Remember that strange, alluring cover on the video store shelf? The one that promised something... else? We're venturing into the Interzone with David Cronenberg's 1991 adaptation of William S. Burroughs' infamous Naked Lunch.

This isn't a film you simply watch; it's a fever dream you endure, a hallucinatory transmission from the darkest corners of addiction, paranoia, and creative desperation. Forget straightforward narrative. Cronenberg, perhaps the only filmmaker brave or mad enough to tackle Burroughs' supposedly "unfilmable" text, doesn't adapt the book page-by-page. Instead, he concocts a potent brew, mixing elements from the novel with Burroughs' other writings and, chillingly, biographical details from the author's own troubled life – specifically the horrifying accidental shooting of his wife, Joan Vollmer. The result is less a story, more an immersive descent.

### Bugs, Drugs, and Typewriters

We follow William Lee (Peter Weller, perfectly cast with his gaunt face and haunted eyes), an exterminator who gets high on his own supply – bug powder. This toxic indulgence becomes the gateway, warping his reality. His typewriter, a sturdy Smith Corona, morphs into a giant, talking beetle, issuing cryptic assignments and demanding reports. His wife, Joan (a mesmerizing Judy Davis, pulling double duty later as the wife of another writer), injects the powder straight into her veins, craving its bizarre psychoactive effects. This domestic scene, already steeped in grime and quiet desperation, curdles into outright nightmare after Lee, attempting a "William Tell routine," tragically shoots Joan – an echo of Burroughs' own devastating past.

Fleeing reality, or perhaps burrowing deeper into his own fractured psyche, Lee finds himself dispatched to Interzone, a surreal, North Africa-inspired purgatory populated by spies, addicts, sentient creatures, and fellow expatriate writers like the stoic Hank (Ian Holm) and the cheerfully cynical Martin (Roy Scheider). Here, the lines blur completely. Is Lee a secret agent? Is he losing his mind? Is the bug powder merely a catalyst, or is it the very substance of this warped reality? Cronenberg offers no easy answers, immersing us instead in the subjective horror of Lee's experience. Reportedly, Burroughs himself was surprisingly pleased with the film, remarking that Cronenberg had managed to film not just Naked Lunch, but elements woven from his entire literary output and life – a testament to the director's deep understanding of the source material's spirit, if not its literal text.

### The Visceral Art of Unease

What truly makes Naked Lunch burrow under your skin, even decades later, are the practical creature effects and the pervasive atmosphere of decay. The Mugwump, that strange, vaguely humanoid creature with the phallic appendage emerging from its head, secreting its addictive fluid... doesn't that design still feel unnerving? These aren't jump-scare monsters; they are grotesque embodiments of addiction, repressed sexuality, and the parasitic nature of Lee's "assignments." The talking beetle typewriters, the Centipede creature, the Mugwump "doctors" – they possess a tangible, unsettling physicality that CGI rarely achieves. These creations, brought to life by the wizards at Chris Walas, Inc. (Walas being famous for Gremlins and The Fly remake), feel disturbingly organic, extensions of the film's biological and psychological horror. There’s a story that Peter Weller became quite attached to the Mugwump puppet, treating it almost like a co-star on set, which somehow makes its appearances even creepier.

Complementing the visuals is the legendary score by Howard Shore, collaborating frequently with Cronenberg. Here, Shore enlisted the free jazz brilliance of Ornette Coleman, whose dissonant, improvisational saxophone riffs perfectly capture the unpredictable, dangerous energy of Interzone. The music isn't just background noise; it's the nervous system of the film, twitching and spasming along with Lee's deteriorating sanity. The production design, contrasting the grimy, nicotine-stained New York apartment with the sun-bleached, yet equally oppressive, architecture of Interzone (filmed primarily on elaborate Toronto soundstages), further cements the feeling of inescapable dread.

### Not an Easy Trip

Let's be honest, Naked Lunch isn't a casual Friday night rental. It demands attention, patience, and a strong stomach. Its exploration of addiction, homosexuality (handled with a matter-of-factness revolutionary for its time, mirroring Burroughs' own life), control, and the often-terrifying process of artistic creation is dense and challenging. The film doesn't offer catharsis or easy resolution. It plunges you into ambiguity and leaves you there, marinated in its unique blend of noir, body horror, and existential dread. When it hit screens in 1991, after Cronenberg had nursed the project for nearly a decade, its reception was predictably mixed. Critics lauded its artistry and ambition, while audiences were often baffled or repulsed. Made for around $17-18 million, it wasn't a box office smash, but its legacy as a daring, uncompromising piece of cult cinema was quickly cemented.

Did it resonate with you back then, watching it on a fuzzy CRT screen? Did the sheer, unapologetic weirdness pull you in or push you away? For me, discovering Naked Lunch on VHS felt like finding forbidden knowledge, a transmission from a frequency rarely broadcast. It was confusing, disturbing, yet utterly hypnotic.

---

Rating: 8/10

Justification: Naked Lunch earns an 8 not for being conventionally entertaining, but for its singular artistic vision, its masterful creation of atmosphere, and its audacious attempt to translate the seemingly untranslatable. Cronenberg crafts a disturbing, complex, and visually unforgettable journey into the heart of addiction and paranoia. Peter Weller is perfect, the practical effects are iconic, and the score is legendary. It loses points only because its challenging, often repulsive nature makes it inaccessible and deliberately difficult for a mainstream audience, but as a piece of uncompromising filmmaking, it's a towering achievement.

Final Thought: Decades later, Naked Lunch remains a potent and disturbing cocktail. It’s a film that doesn’t just depict a nightmare, it invites you to live inside one for two hours, leaving a residue that’s hard to wash off. A true artifact of challenging cinema from the VHS era.