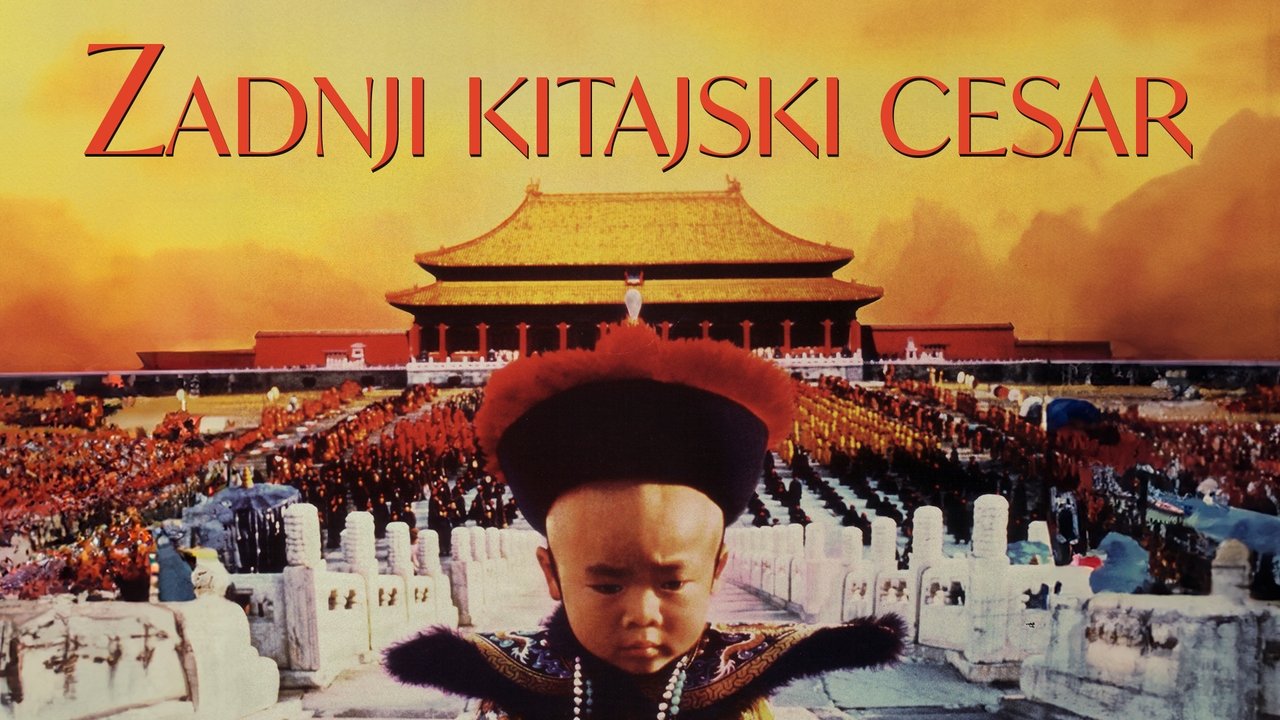

It's a strange sensation, isn't it? Thinking back to the sheer, unexpected scale that sometimes emerged from those chunky plastic VHS tapes. You’d slot one into the VCR, the machine would whir and clunk, and suddenly your flickering CRT screen would be filled not just with a story, but with history itself, vast and overwhelming. Few films captured that feeling quite like Bernardo Bertolucci's 1987 masterpiece, The Last Emperor. This wasn't just a movie; watching it felt like witnessing an event, something monumental achieved against improbable odds. And the most incredible fact, the one that still echoes? Bertolucci was granted unprecedented permission – the first Western filmmaker ever – to shoot within the imposing, mysterious walls of Beijing's Forbidden City.

A Life Between Worlds

The film chronicles the tumultuous life of Pu Yi, the titular last emperor of China, played with captivating nuance across different ages, culminating in a mesmerizing performance by John Lone. We see him ascend the Dragon Throne as a bewildered toddler in 1908, cocooned within the ancient rites and suffocating opulence of the Forbidden City, utterly detached from the seismic shifts happening outside its gates. From imperial deity to pampered prisoner of tradition, then a puppet ruler for the Japanese, a Soviet captive, and finally, a humble gardener in Communist China – Pu Yi's journey is less a narrative arc and more a collision course with the relentless forces of 20th-century history. What does it mean to be stripped of not just power, but identity itself, over and over again? The film doesn't offer easy answers, instead immersing us in the sensory details of his confinement and eventual, jarring reentry into the world.

Captive Audience, Captive Emperor

Bertolucci uses the Forbidden City not just as a backdrop, but as a character. Its vast courtyards and intricate chambers represent both infinite power and inescapable imprisonment. Cinematographer Vittorio Storaro, already legendary for his work on Coppola's Apocalypse Now (1979), paints with light and shadow, contrasting the warm, golden hues of the imperial past with the colder, starker tones of Pu Yi's later life. The visual storytelling is breathtaking. Remember the scene where the young emperor chases a runaway rat, only to find his path blocked by the giant, unyielding gates? It’s a simple image, yet it speaks volumes about his gilded cage. He is master of everything within sight, yet powerless to leave.

Faces in the Imperial Court

The performances are key to grounding this epic sweep in human emotion. John Lone is simply magnificent as the adult Pu Yi. Drawing perhaps on his own background in Peking Opera, he conveys a lifetime of suppressed longing, confusion, and fragile dignity, often through stillness and subtle glances. His Pu Yi is tragic, sometimes pathetic, but always compellingly human. Alongside him, Joan Chen delivers a heartbreaking performance as Empress Wanrong, whose initial vivacity curdles into despair and addiction under the weight of imperial decay and personal neglect. And then there’s Peter O'Toole, bringing his signature blend of wry intelligence and weary grandeur to the role of Reginald Johnston, Pu Yi’s Scottish tutor. Johnston represents a window to the outside world, offering knowledge but ultimately unable to alter the trajectory of his pupil's fate. O'Toole, no stranger to epics after Lawrence of Arabia (1962), lends the film an essential gravitas.

Behind the Imperial Gates: Crafting the Spectacle

The making of The Last Emperor is almost as epic as the story itself. Convincing the Chinese government to allow filming within the sacred Forbidden City was a diplomatic coup for Bertolucci. The logistics were staggering: reports mention coordinating up to 19,000 extras, many drawn from the People's Liberation Army, for the crowd scenes. Imagine the sheer manpower involved! Thousands of costumes were meticulously researched and created. Bertolucci and his team navigated complex cultural and political sensitivities, a testament to their dedication. This dedication paid off critically and commercially; made for roughly $23.8 million (around $65 million today), it grossed a respectable $44 million domestically, a significant sum for a nearly three-hour historical drama in the late 80s.

Furthermore, the film swept the 60th Academy Awards, winning all nine Oscars it was nominated for, including Best Picture, Best Director for Bertolucci, and Best Cinematography for Storaro. The haunting, evocative score – a unique collaboration between Ryuichi Sakamoto (who also has a small acting role as the manipulative Japanese officer Masahiko Amakasu), David Byrne (of Talking Heads fame), and Cong Su – also deservedly took home an Oscar. For the dedicated VHS hunters out there, it's worth noting that longer, extended cuts were sometimes broadcast on television, offering even more detail than the already substantial theatrical release.

Legacy on Tape and Time

Watching The Last Emperor today, perhaps even digging out an old VHS copy if you're lucky enough to still have a player, remains a powerful experience. It’s a film that demands patience but rewards it immensely. It’s a history lesson wrapped in astonishing visuals and intimate human drama. It makes you ponder the dizzying turns of fate, the weight of tradition, and the struggle to find oneself when the world insists on defining you. It stands as a high watermark for the historical epic, a testament to bold filmmaking ambition realized on a truly grand scale. It wasn't just a rental; it felt like bringing a piece of cinematic history home.

Rating: 9/10

The score reflects the film's monumental achievement in scope, craft, and performance. Its visual grandeur is undeniable, the storytelling is deeply affecting, and the performances, particularly Lone's, are superb. It’s a near-perfect execution of an incredibly ambitious vision, only perhaps slightly hampered for some by its deliberate pacing in places.

The Last Emperor reminds us that even within the most imposing structures and sweeping historical tides, the quiet struggles of the human heart remain the most compelling story of all. A true emperor of 80s cinema.