What if you were riding alongside history, but just slightly out of frame? That's the peculiar, captivating sensation at the heart of Ettore Scola's The Night of Varennes (1982, La Nuit de Varennes). It doesn't thrust us into the panicked flight of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette in June 1791; instead, it places us in a parallel stagecoach, a microcosm of French society trundling along the same road, filled with characters who are observers, commentators, and perhaps, relics of a world unknowingly about to vanish. It's a film that unfolds less like a traditional historical epic and more like a series of intense, whispered conversations in the dark, pregnant with the weight of impending change.

Shadows on the Road to Revolution

The premise itself is wonderfully theatrical: a diverse group – including the aging, legendary libertine Giacomo Casanova (Marcello Mastroianni), the prolific and sometimes scandalous writer Restif de la Bretonne (Jean-Louis Barrault), a politically engaged American, Thomas Paine (Harvey Keitel, though his role is smaller), and the enigmatic Countess Sophie de la Borde (Hanna Schygulla) – find themselves sharing a carriage journey from Paris. Their paths inadvertently mirror the doomed royal family's escape attempt towards the border fortress of Montmédy, which famously ended with their capture in the small town of Varennes-en-Argonne. Scola, working with frequent collaborator Sergio Amidei on the screenplay, isn't interested in the chase itself, but in the ripples it creates, the anxieties it surfaces, and the reflections it provokes among those caught in its periphery. The air hangs thick with rumour, dust, and the dawning realization that the old order is fracturing.

Portraits in a Fading Light

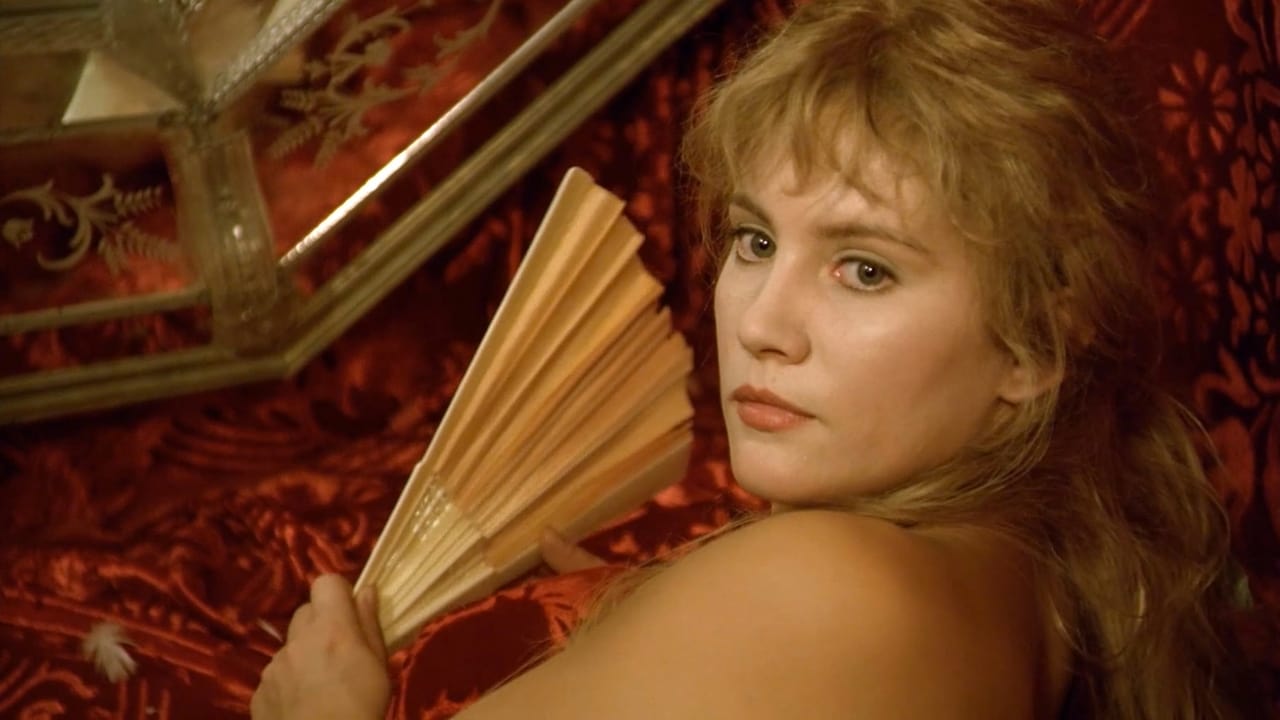

The true brilliance lies in the ensemble cast, particularly the European titans anchoring the journey. Jean-Louis Barrault, a legend of French theatre and cinema (Children of Paradise), embodies Restif with a restless, almost voyeuristic energy. He is the chronicler, notebook perpetually in hand, trying to capture the essence of a moment he perhaps doesn't fully grasp. But it's Marcello Mastroianni who delivers a performance of profound melancholy and weary elegance as Casanova. This isn't the virile adventurer of legend; this is Casanova in twilight, his reputation preceding him, yet seemingly more interested in philosophical musings and quiet comforts than further conquests. Mastroianni imbues him with a touching vulnerability, a man aware that his era, much like his youth, is irrevocably slipping away. There's a scene where he simply tries to enjoy an egg, a small moment of personal ritual amidst the surrounding chaos, that speaks volumes. Hanna Schygulla, a muse of Rainer Werner Fassbinder, brings her characteristic enigmatic presence to the Countess, a confidante of the Queen, carrying secrets and anxieties beneath a composed exterior. Their interactions, full of coded language, regret, and intellectual sparring, form the film's mesmerizing core.

Scola's Thoughtful Stage

Ettore Scola, known for intimate dramas often set in confined spaces like A Special Day (1977), uses the stagecoach and roadside inns not just as settings, but as stages for philosophical debate and personal revelation. The direction is deliberate, patient. He allows conversations to breathe, favoring character moments over historical spectacle. The cinematography by Armando Nannuzzi beautifully captures the candlelit interiors and the dusty, sun-drenched French countryside, creating a tangible sense of time and place. It feels less like watching a movie and more like eavesdropping on history's waiting room. Does this deliberate pace sometimes test the patience of viewers accustomed to more conventional historical narratives? Perhaps. But the reward is a far richer, more contemplative experience.

Echoes from the Archives (Retro Fun Facts)

Digging into this film reveals some fascinating layers:

- Historical Cameos: The genius of the script lies in placing real historical figures – Casanova, Restif, Paine – into this fictionalized encounter. While Casanova was alive in 1791, his presence on this specific journey is Scola's invention, a poignant "what if?" imagining the ultimate symbol of the Ancien Régime's pleasures confronting its demise. Restif de la Bretonne, however, was a known chronicler of Parisian life during the revolution, making his observer role historically resonant.

- Mastroianni's Casanova: Casting Mastroianni, often associated with suave, romantic leads (La Dolce Vita, 8½), as an aged, almost Cennui-ridden Casanova was inspired. It allowed him to explore themes of mortality and relevance that resonated deeply, offering a counterpoint to the usual depictions of the great lover. Scola and Mastroianni had a fruitful collaboration, and this role feels like a particularly insightful culmination.

- An Arthouse Affair: Unlike bombastic Hollywood historical epics, The Night of Varennes was very much a European arthouse production. Its budget was modest for a period piece (estimated around $5-6 million), relying on authentic locations and strong performances rather than grand battles. Its success was critical rather than commercial in the blockbuster sense, finding its audience among cinephiles – precisely the kind of film you might have discovered tucked away in the 'Foreign Films' section of a more adventurous video store, a welcome discovery after scanning rows of action flicks.

- The Missing Paine?: While Harvey Keitel's name adds star power, Thomas Paine's role is surprisingly brief. Some accounts suggest his part might have been intended to be larger, but the final cut focuses more squarely on the European characters wrestling with the continent's upheaval.

The Weight of Observation

What lingers long after the credits roll is the film's profound meditation on witnessing history versus participating in it. Restif frantically scribbles notes, Casanova reflects on past glories, the Countess worries about her Queen – they are all reacting, processing, but ultimately powerless to alter the course of events unfolding just ahead of them on the road. Doesn't this resonate with how we often experience major world events today – through screens, reports, discussions, slightly removed from the epicenter? The film seems to ask: what is the responsibility of the observer? Is simply recording events enough, or does understanding require something more?

Rating Justification & Final Thought

8/10

The Night of Varennes earns a strong 8 out of 10. It's a beautifully crafted, intelligent, and deeply affecting film, anchored by superb performances, particularly from Mastroianni and Barrault. Its unique approach to historical drama – focusing on the periphery rather than the center – is its greatest strength, offering a rich tapestry of ideas about change, aging, and the end of an era. The deliberate pacing and dialogue-heavy nature might not appeal to all tastes, preventing a higher score for universal accessibility, but for those seeking thoughtful, character-driven cinema, it's exceptional. The atmosphere is palpable, and Scola's direction is masterful in its restraint and focus.

This is the kind of film that might have felt like a rare treasure unearthed on VHS – a sophisticated, European counterpoint to the louder fare of the era. It doesn’t offer easy answers or thrilling action, but invites you into a quiet, profound reflection on a world turning upside down, leaving you pondering not just the fate of kings and queens, but the echoes of their passage in the lives of ordinary, and extraordinary, witnesses.