It begins not with a whisper, but with a primal scream echoing across a sun-drenched Italian landscape, juxtaposed against the soaring grandeur of Verdi. This immediate, almost jarring clash sets the stage for Bernardo Bertolucci’s Luna (1979), a film that arrived on home video shelves like a beautifully packaged, yet deeply unsettling, artifact. It wasn't the usual Friday night rental fare, sitting perhaps uneasily between the action flicks and comedies. Discovering it felt like unearthing something forbidden, a complex, operatic drama grappling with themes most mainstream cinema wouldn’t dare touch.

An Unraveling Tapestry

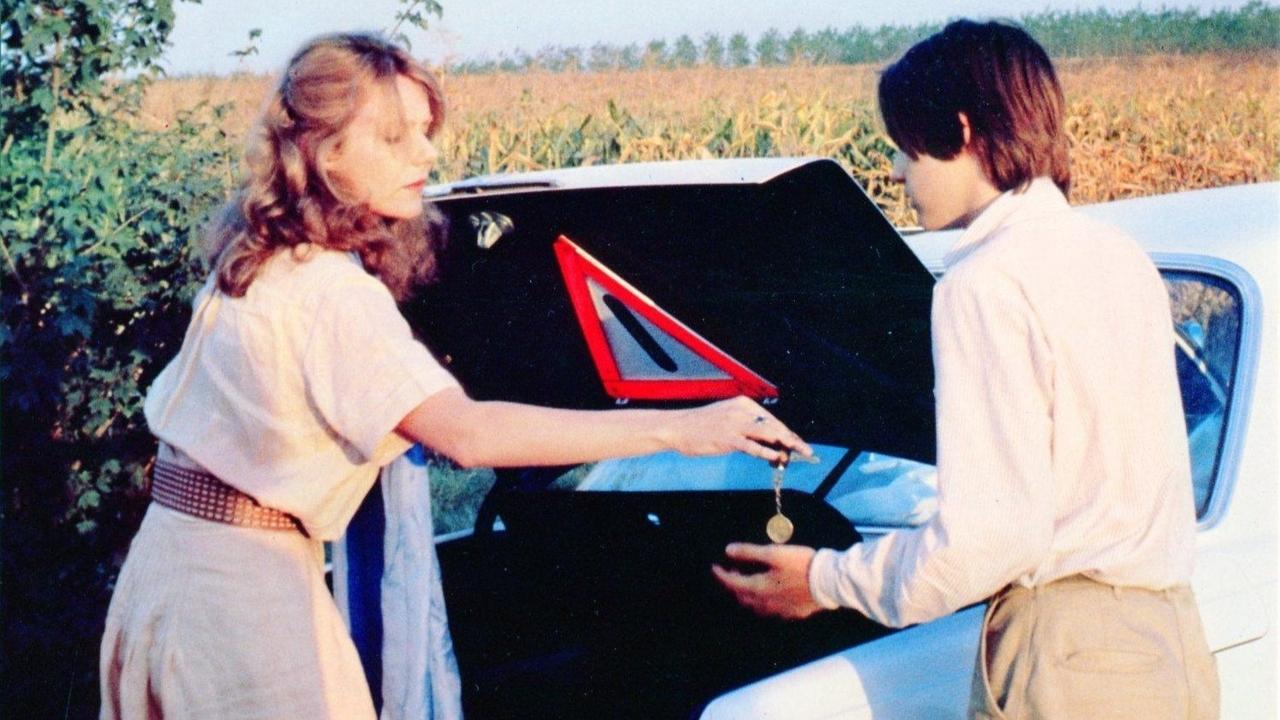

At its heart, Luna follows Caterina (Jill Clayburgh), a globally renowned American opera singer whose life fractures when her husband Douglas (Fred Gwynne, miles away from Herman Munster) dies suddenly in New York. Seeking solace and perhaps escape, she relocates to Italy with her sullen, increasingly distant fifteen-year-old son, Joe (Matthew Barry). But Italy offers no simple refuge. Instead, it becomes the backdrop for Joe’s descent into heroin addiction and the unraveling of Caterina’s carefully constructed world, forcing their already fraught relationship into dangerously intimate territory. Bertolucci, never one to shy away from psychological intensity (as seen in Last Tango in Paris just a few years prior), plunges us headfirst into their shared grief, alienation, and desperate, misguided attempts at connection.

Clayburgh’s Courageous Descent

One cannot discuss Luna without focusing on Jill Clayburgh. Fresh off her powerhouse, Oscar-nominated performance as a woman finding independence in An Unmarried Woman (1978), taking on Caterina was an act of immense creative bravery. It’s a performance stripped bare, oscillating wildly between the commanding presence of a diva on stage and the raw, messy anguish of a mother watching her son self-destruct. Clayburgh throws herself into the role with a vulnerability that is often difficult to watch, yet utterly compelling. She embodies Caterina’s contradictions – her narcissism, her smothering love, her profound loneliness. The moments where her facade cracks, revealing the terror beneath, are unforgettable. It’s said Bertolucci initially considered others, like Liv Ullmann, but Clayburgh, perhaps a less expected choice, brings a distinctly American, almost brittle energy that feels vital to the character’s dislocation in the Old World.

Opera, Addiction, and Taboo

Bertolucci uses opera not merely as a backdrop, but as a thematic resonator. The heightened emotions, the grand tragedies, the soaring arias – they mirror the intense, almost unbearable drama unfolding between mother and son. The film is visually stunning, thanks to the masterful eye of cinematographer Vittorio Storaro (who, incredibly, also shot Apocalypse Now the very same year). Storaro paints Italy with light and shadow, creating compositions that are both breathtakingly beautiful and deeply melancholic, perfectly capturing the film's internal state.

Yet, beneath the visual splendor lies the film’s notorious core: the exploration of an incestuous undercurrent, culminating in a deeply controversial act born of desperation. This is where Luna demands serious reflection. Is it exploitative? Or is Bertolucci attempting something more complex – using this transgression to illustrate the absolute breakdown of boundaries, the terrifying lengths a mother might go to in a misguided attempt to save, or perhaps reclaim, her child? The film doesn't offer easy answers, forcing the viewer to confront uncomfortable questions about dependency, intimacy, and the destructive nature of unresolved grief. The depiction of Joe's addiction, too, feels harrowing and bleak, a stark contrast to the operatic grandeur surrounding them.

A Challenging Discovery

Finding Luna on VHS, perhaps nestled in the "Drama" section of a dusty rental store, was often an accidental encounter with serious, challenging European arthouse cinema. It certainly wasn't an easy watch then, and it remains provocative today. Its narrative can feel meandering, even self-indulgent at times, and the central taboo remains deeply unsettling. The film was met with largely negative reviews upon release and struggled significantly at the box office (reportedly grossing far less than its $1.7 million budget), dismissed by many as overwrought or distasteful.

Yet, dismissing it entirely feels wrong. There's an undeniable power in its audacity, in Clayburgh's fearless performance, and in Bertolucci and Storaro's potent visual language. It’s a film that lingers, not necessarily comfortably, but persistently. It raises questions about the limits of love, the scars of loss, and the ways trauma can warp human connection. Was this the kind of film you watched repeatedly? Probably not. But encountering it, perhaps when you were expecting something simpler, felt significant – a reminder of cinema’s power to provoke and disturb, not just entertain.

Rating: 6/10

Luna is undeniably flawed, often opaque, and treads into territory that remains profoundly uncomfortable. Its pacing drags in places, and its emotional pitch can sometimes tip into melodrama. However, Jill Clayburgh's towering performance, Vittorio Storaro's sublime cinematography, and Bernardo Bertolucci's sheer, unflinching audacity make it a film that’s hard to forget. It earns a 6 not for easy enjoyment, but for its challenging artistry and the lasting resonance of its central, painful questions.

It remains a difficult, sometimes brilliant, often frustrating piece of work – a testament to a time when mainstream-adjacent cinema dared to be truly dangerous. What stays with you isn't comfort, but the unsettling echo of its operatic despair.