Okay, let's dim the lights, maybe pour a glass of something thoughtful, and slide this tape into the VCR. Some films from the era hit you with neon and synth-pop, but others, like 1989's Fat Man and Little Boy, demand a different kind of engagement. This isn't a feel-good blockbuster; it's a film wrestling with the immense weight of history, attempting to capture the moment humanity unlocked the terrifying power to annihilate itself. What does it truly mean to pursue knowledge when the potential cost is so catastrophic? That question hangs heavy over every frame.

The Desert Bloom of Destruction

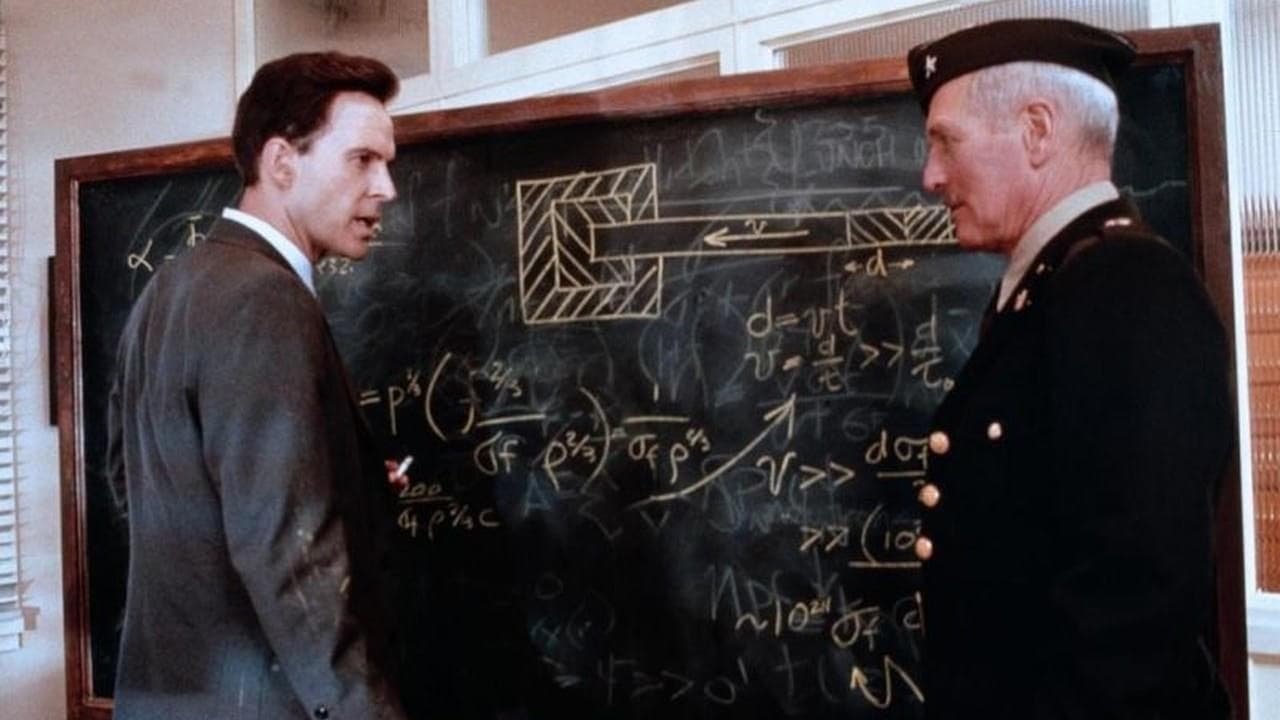

Director Roland Joffé, fresh off acclaimed, morally complex dramas like The Killing Fields and The Mission, brings a certain gravitas to the proceedings. The film drops us into the stark, secretive world of the Manhattan Project in Los Alamos, New Mexico – though interestingly, the bulk of the filming took place on meticulously recreated sets built near Durango, Mexico. You can almost feel the dusty isolation, the strange juxtaposition of cutting-edge theoretical physics unfolding against a backdrop of military urgency and rugged terrain. Joffé attempts to capture the pressure-cooker atmosphere, the ticking clock of World War II driving brilliant minds towards a goal many only partially comprehended the implications of. The plot, co-written by Joffé and Bruce Robinson (an intriguing pairing, given Robinson's sharp, cynical work on Withnail & I), focuses primarily on the relationship between the project's military overseer, General Leslie Groves, and its scientific director, J. Robert Oppenheimer.

Giants Under Pressure: Newman and Schultz

The casting is perhaps the film's most discussed aspect, particularly concerning the central duo. The legendary Paul Newman, exuding seasoned authority and weary determination, steps into the boots of General Groves. Newman delivers a typically solid performance, conveying the immense burden of command and the pragmatic, often ruthless, drive required to marshal such an unprecedented, high-stakes operation. He embodies the military mindset – get the job done, win the war, deal with the fallout later. You see the weight on his shoulders, the understanding that failure isn't an option, yet perhaps a flicker of unease about the genie they're letting out of the bottle. It’s a grounded, believable portrayal of leadership under unimaginable stress.

More debated is Dwight Schultz as J. Robert Oppenheimer. Known widely then (and perhaps still now) as the lovably eccentric 'Howling Mad' Murdock from TV's The A-Team, casting him as the complex, theoretically brilliant, and morally tormented father of the atomic bomb was certainly a choice. Does he fully capture the man's almost ethereal genius and profound inner conflict? That's where opinions diverge. Schultz certainly conveys Oppenheimer's intensity and dedication, but some viewers found the portrayal lacked the nuanced depth or perhaps the inherent intellectual charisma associated with the historical figure. It's a demanding role, asking for both towering intellect and deep vulnerability, and while Schultz gives it his all, the shadow of his more famous comedic persona might have been difficult for some audiences in 1989 to shake. Supporting players like Bonnie Bedelia (familiar from Die Hard), John Cusack, and Laura Dern add texture, often representing the human cost or ethical counterpoints simmering beneath the main thrust of the narrative.

Recreating Trinity (Retro Fun Facts)

Bringing the Manhattan Project to life was no small feat. The production reportedly spent a significant portion of its hefty $30 million budget (around $74 million in today's money) constructing the Los Alamos replica in Mexico. This commitment to scale gives the film a tangible sense of place. Joffé aimed for historical accuracy in depicting the environment and the immense scientific and engineering challenges, though dramatic license inevitably shapes the personal interactions. One fascinating detail often overlooked is the film's title itself – "Fat Man" and "Little Boy" were, of course, the grim codenames for the atomic bombs dropped on Nagasaki and Hiroshima, respectively. Using these names as the title lends an immediate, chilling weight, foreshadowing the devastating endpoint of the project from the outset. Despite the star power and serious subject matter, the film struggled at the box office, recouping only about $16 million worldwide. Perhaps audiences in '89 weren't quite ready for such a stark examination of this pivotal, morally complex moment, or maybe the mixed critical reception dampened enthusiasm.

The Ethical Crucible

Where Fat Man and Little Boy truly resonates, particularly watching it today through the lens of history and countless subsequent debates about nuclear proliferation, is in its exploration of the ethical dilemmas. The film doesn't shy away from the internal conflicts faced by the scientists, the push-and-pull between patriotic duty, scientific curiosity, and dawning horror. It raises questions about the responsibility of creators for their creations, the point at which the pursuit of knowledge must be tempered by moral consideration, and the uneasy alliance between scientific advancement and military power. Does the film offer easy answers? Thankfully, no. It presents the situation, the personalities, the pressures, and leaves the viewer to grapple with the profound implications. Isn't that what thoughtful filmmaking should do – provoke, rather than preach?

Lasting Echoes

Fat Man and Little Boy may not be the definitive cinematic account of the Manhattan Project (especially with more recent depictions gaining attention), but it remains a significant, serious-minded attempt from the late VHS era to tackle one of the 20th century's most crucial and terrifying turning points. Newman provides a compelling anchor, and Joffé crafts moments of palpable tension and visual power. While the portrayal of Oppenheimer might divide viewers, the film succeeds in immersing us in the unique atmosphere of Los Alamos and forcing us to confront the monumental weight of the scientists' work. It’s a film that lingers, not necessarily for its narrative triumphs, but for the sheer gravity of the history it depicts.

Rating: 6.5/10

Justification: The film gets points for its ambitious scope, Newman's strong performance, and its willingness to engage with complex ethical themes. Joffé's direction creates a palpable sense of time and place. However, it's held back somewhat by a script that occasionally feels unfocused and the contentious casting/portrayal of Oppenheimer, which doesn't quite reach the heights the role demands. The historical weight carries it, but dramatic execution feels slightly uneven.

Final Thought: A somber, sometimes flawed, but undeniably thought-provoking trip back to a moment when humanity stared into the abyss of its own creation, leaving us to wonder if we truly learned the lessons forged in that desert crucible.