Okay, fellow travelers through the tangled wires and magnetic dust of VHS Heaven, dim the lights and settle in. Some tapes you slide into the VCR carry an almost palpable static charge, a warning whispered on the magnetic tape itself. Crawlspace, the 1986 offering from David Schmoeller (who would later unleash the Puppet Master series), is precisely that kind of tape. It doesn't just present a story; it exudes a clammy, uncomfortable dread that clings long after the credits roll and the machine clicks off.

### The Landlord You Pray You Never Meet

The premise is deceptively simple, tapping into a primal fear: the violation of one's sanctuary. Dr. Karl Gunther rents out apartments in his building, but he's no ordinary landlord. He's the son of a Nazi surgeon, a disturbed individual who listens to his tenants through the vents, watches them through hidden peepholes, and ensnares them in elaborate, deadly traps within the building's hidden passages – the titular crawlspace. It’s a setup ripe for claustrophobic terror, turning the seemingly safe space of home into a predator's labyrinth. Remember that vague unease some apartment buildings just have? Crawlspace weaponizes it.

### A Portrait Etched in Ice and Fury

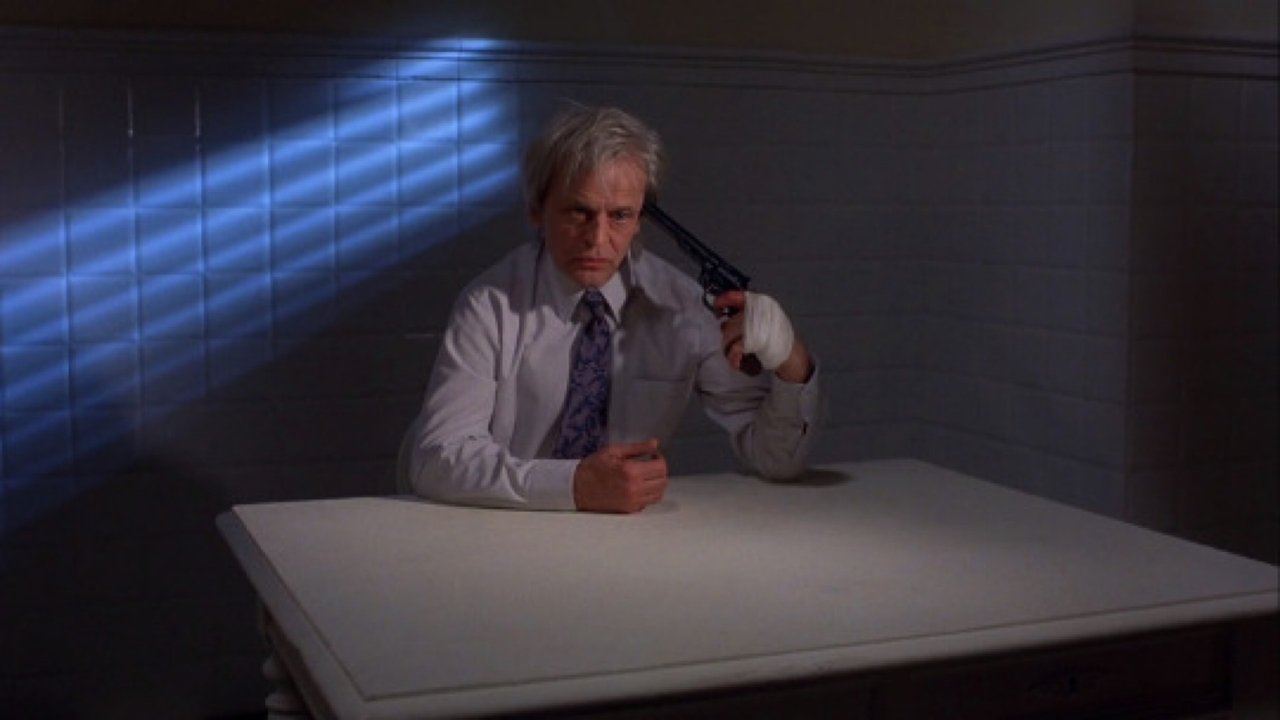

Central to the film's chilling effectiveness, and indeed its entire troubled existence, is the magnetic yet monstrous performance of Klaus Kinski as Gunther. Kinski doesn't just play mad; he radiates a dangerous, unpredictable energy that feels terrifyingly real. His Gunther is quiet, precise, almost clinical in his cruelty, punctuated by those sudden, volcanic bursts of rage Kinski was infamous for. His piercing blue eyes seem to bore directly through the screen, implicating the viewer in his voyeurism. There's a moment where he simply stares, silently, and it’s more unnerving than any jump scare could ever be. Doesn't that intense, unwavering gaze still feel deeply unsettling?

The performance is inseparable from the film's "dark legend." David Schmoeller has been famously candid about the nightmare of working with Kinski. The actor's legendary tantrums, abusive behavior towards cast and crew (Talia Balsam, playing the resourceful tenant Lori, reportedly bore the brunt of much of it), and general volatility created an atmosphere of genuine fear on set. Schmoeller even documented his desire to genuinely harm Kinski in his short film Please Kill Mr. Kinski. Knowing this backstory adds a grim layer to watching Crawlspace; the on-screen menace feels disturbingly amplified by the off-screen reality. It wasn't just acting; it was Kinski being Kinski, captured on celluloid. This film was reportedly shot in just over 20 days, a testament perhaps less to efficiency and more to simply getting Kinski's part finished as quickly as humanly possible.

### Echoes in the Walls

Beyond Kinski, Schmoeller crafts a genuinely oppressive atmosphere. The production design, though likely constrained by its estimated $1 million budget (a modest sum even then), uses the cramped apartment building to great effect. The vents aren't just plot devices; they feel like Gunther's arteries, connecting him to every corner of his domain. The crawlspace itself is a shadowy, threatening void. The score, a typical 80s synth affair by Pino Donaggio (a frequent Brian De Palma collaborator who scored Carrie (1976) and Dressed to Kill (1980)), manages to be effectively eerie, underscoring the psychological tension rather than just telegraphing shocks.

The film revels in Gunther's twisted ingenuity. His methods of dispatch are often cruel and mechanical – automated drills, cages, a chair designed for execution. These practical effects, relics of the pre-CG era, have that tangible quality that could feel disturbingly plausible back when you were watching on a flickering CRT. Remember how those whirring drills and snapping traps felt so much more visceral?

### An Artifact of Unease

Crawlspace isn't a perfect film. Its pacing can sometimes drag between moments of tension, and the supporting characters often feel more like props for Gunther's machinations than fully fleshed-out individuals. Some elements, like Gunther's tape-recorded confessions and his bizarre self-preservation ritual involving removing his own larynx (a strange, somewhat underdeveloped plot point), lean towards the lurid exploitation territory common in Empire Pictures releases.

Yet, it transcends its limitations primarily through Kinski's sheer force-of-nature presence and the pervasive sense of claustrophobia. It’s a film that makes you profoundly uncomfortable, tapping into fears of surveillance, loss of control, and the monster hiding in plain sight. It's the kind of nasty little gem you'd discover nestled between bigger titles at the video store, rent on a whim, and then find yourself thinking about days later, maybe nervously checking the vents in your own place. I distinctly remember renting this one late on a Friday night, drawn in by Kinski’s face on the cover, and feeling genuinely creeped out by its quiet intensity.

---

Rating: 7/10

Justification: Crawlspace earns its score through its masterful cultivation of dread, a truly unforgettable (and genuinely frightening) central performance from Klaus Kinski, and its effective use of a claustrophobic setting. While hampered slightly by pacing issues and thin supporting characters typical of its budget and era, its power to disturb remains potent. The grim behind-the-scenes reality only adds to its unsettling legacy.

Final Thought: More psychological horror than outright slasher, Crawlspace remains a potent reminder from the VHS shelves that sometimes the most terrifying monsters are the ones who hold the keys to your front door. It’s a dirty, uncomfortable, and strangely compelling watch, forever marked by the chilling presence at its dark heart.