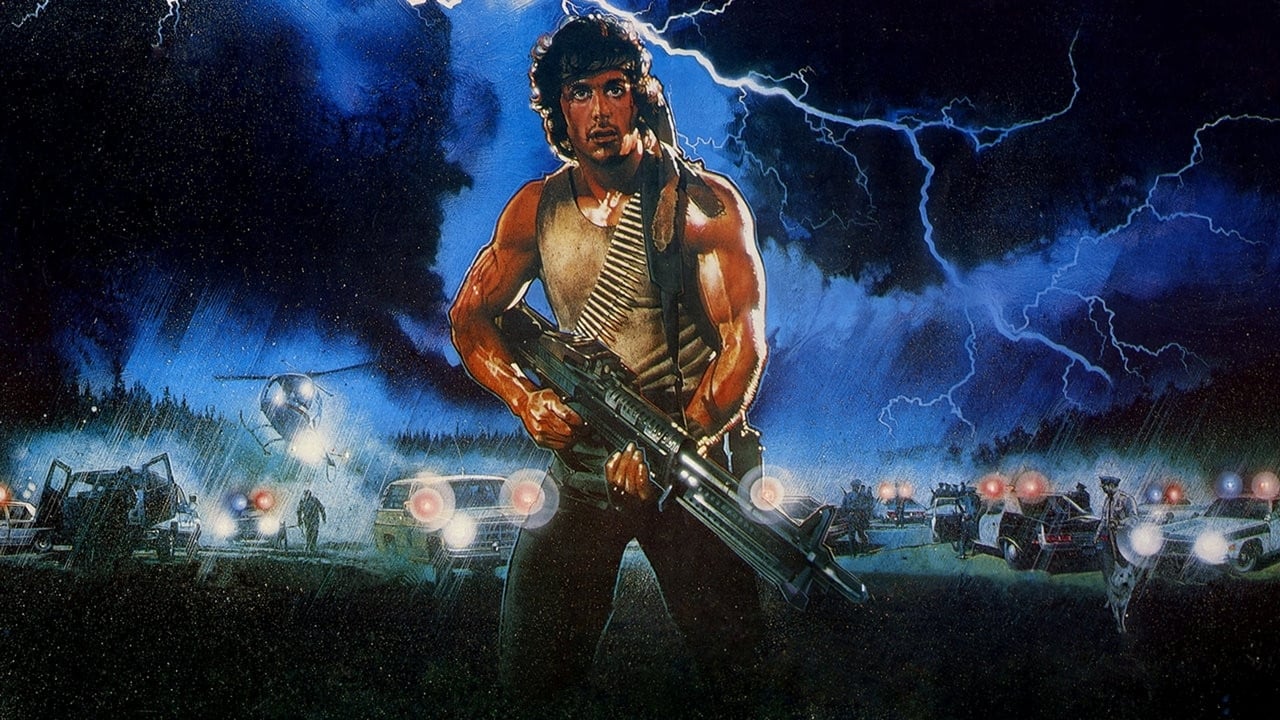

There's a chill that settles deep in your bones when the fog rolls through the pines of the Pacific Northwest, a damp quiet that feels both peaceful and menacing. That's the precise feeling Ted Kotcheff bottles in First Blood (1982). Forget the explosive cartoonery that followed; this first outing for John Rambo is a raw, surprisingly bleak survival thriller, a film that felt less like an action flick and more like a tightly wound nerve snapping when you first slid that well-worn VHS tape into the machine late one Friday night.

Not the War You Expected

The setup is deceptively simple, almost mundane. A man, Sylvester Stallone looking leaner and far more haunted than his later, more iconic physique, drifts into the small town of Hope. He's John Rambo, looking for an old Green Beret buddy, only to find his friend has already succumbed to cancer caused by Agent Orange exposure. This immediate brush with the lingering death of war sets a somber stage. When the local sheriff, Teasle – played with simmering, petty malice by the great Brian Dennehy – takes an instant dislike to the vagrant veteran, things escalate with terrifying speed. It’s not explosions and quips; it’s the slow, grinding gears of authority misused, pushing a man trained for hell back into it. Dennehy embodies that small-town power trip perfectly, a man whose pride becomes the flint striking Rambo's steel.

Into the Woods

The escape into the wilderness is where First Blood truly finds its footing, transforming into a desperate game of cat and mouse. Kotcheff uses the dense, wet forests of British Columbia (standing in for Washington state) to create a claustrophobic nightmare. The rain feels constant, the mud inescapable. You feel the cold seep into Rambo's bones as he relies purely on instinct and training. This wasn't the CGI-assisted spectacle we see today; the tension came from the palpable danger, the knowledge that every fall, every makeshift trap, felt brutally real. Remember that leap from the cliff into the trees? Sylvester Stallone famously cracked a rib performing that stunt himself, a testament to the commitment to gritty realism that permeated the production. The injuries weren't just makeup; they felt earned. It's this visceral quality, the reliance on practical stunts and effects, that made it hit so hard on those flickering CRT screens.

It's fascinating how close this film came to being radically different, or perhaps not existing at all. Stallone reportedly hated the initial three-hour cut so much he tried to buy the negative to destroy it, feeling it was irredeemable. It was only through significant re-editing, shifting the focus more squarely onto Rambo's perspective and plight, that the lean, impactful film we know emerged. Imagine a world without Rambo because the first cut felt like a disaster – a strange thought for such a cultural touchstone.

"They Drew First Blood"

While the action sequences are tense and brilliantly executed – the police station assault remains a masterclass in controlled chaos – the film's true power lies in Rambo himself. Stallone delivers a performance often overshadowed by his later, more cartoonish portrayals. Here, he's largely silent for stretches, conveying pain, fear, and simmering rage through his eyes and physicality. His eventual breakdown, the famous monologue where decades of trauma pour out ("Nothing is over! Nothing!"), is genuinely affecting. It’s a raw cry from a generation of soldiers discarded and misunderstood upon their return.

This emotional core almost led to a drastically darker conclusion, mirroring David Morrell's original novel. The initial plan, and indeed filmed ending, saw Rambo commit suicide, forcing Colonel Trautman to pull the trigger. Kirk Douglas, initially cast as Trautman, actually walked away from the project partly because he insisted Rambo should die, remaining faithful to the book. When Richard Crenna stepped in (becoming the definitive Trautman), Stallone argued that Rambo surviving, having endured so much, offered a more resonant message for Vietnam veterans. Test audiences agreed, and the ending was changed, paving the way for sequels but perhaps softening the original bleak intent just a touch. Does that changed ending still resonate as powerfully, or did something get lost?

The Echo of Trauma

First Blood wasn't just another action movie; it tapped into a very real post-Vietnam angst simmering in American culture. Made for a modest $15 million (around $47 million today), its $125 million worldwide gross (nearly $390 million adjusted) proved it struck a chord. It presented a veteran not as a hero or a villain, but as a damaged survivor reacting to a hostile environment. Jerry Goldsmith's score, both mournful and tense, perfectly complements this, avoiding triumphalism for something far more haunting. The film felt dangerous, not just in its violence, but in its willingness to portray the psychological scars of war without easy answers. It asked uncomfortable questions about how soldiers were treated upon returning home, questions that echoed long after the credits rolled and the VCR clicked off.

The sequels, starting with Rambo: First Blood Part II (1985), famously shifted gears, turning Rambo into a hyper-muscled, flag-waving superhero. While those films have their own place in 80s action iconography, they lose the grounded desperation and psychological depth that makes First Blood so compelling and enduring. This original feels like lightning caught in a bottle – a tough, smart, and deeply felt thriller that stands apart.

VHS Heaven Rating: 9/10

This rating reflects the film's raw power, Sylvester Stallone's surprisingly vulnerable performance, Ted Kotcheff's taut direction, and its unflinching (for its time) look at veteran trauma. It’s a near-perfect survival thriller whose gritty realism and underlying sadness were often lost in the spectacle of its sequels. The practical effects, the palpable tension, and the haunting atmosphere hold up remarkably well. It loses perhaps a single point for the slightly softened ending compared to the source material, but even with that change, its impact is undeniable.

First Blood remains a cornerstone of 80s action cinema, but it's so much more than that. It’s a reminder that behind the bandana and the body count, there was initially a story about pain, survival, and the cost of war coming home. It still delivers a potent, chilling experience, a true classic from the era of tracking adjustments and worn-out tape covers.