The flickering green text crawl across the monitor wasn't displaying BASIC commands or booting up a game of Zork. No, this machine, an ungainly beige box humming with nascent digital power in the bowels of a suffocating military academy, was translating Latin. Ancient, demonic Latin. Long before networked nightmares became commonplace, 1981’s Evilspeak tapped into a primal, almost quaint fear: what if the sterile logic of computers could interface with the chaotic malevolence of Hell itself? It’s a concept that feels distinctly of its time, yet the resulting film delivers a grimy, satisfyingly nasty slice of revenge horror that still resonates with a certain kind of midnight-movie dread.

Cruel Barracks, Darker Cellars

Our conduit into this low-tech inferno is Stanley Coopersmith, played with excruciating vulnerability by Clint Howard. If ever an actor seemed born to portray the perpetual outcast, it's Howard here. Constantly tormented by hyper-masculine cadets, belittled by the academy staff (save for a sympathetic priest played by Joseph Cortese), Stanley is the archetypal nerd pushed too far. His discovery of a hidden crypt beneath the academy chapel, containing the skeletal remains and grimoire of the exiled Satanist Father Esteban, feels less like chance and more like destiny. Clint Howard, brother of director Ron Howard and already a familiar face from numerous TV appearances, truly anchors the film. You feel every humiliation, making his eventual turn not just horrifying, but disturbingly cathartic. The script apparently underwent significant rewrites, but Howard's portrayal of Stanley's slow burn from victim to vengeful vessel remains the film's strongest asset.

The military academy setting itself provides a stark, oppressive backdrop. Director Eric Weston (who also co-wrote) uses the rigid conformity and inherent cruelty of the place to amplify Stanley’s isolation. Filming reportedly took place at a former military school in California, lending an air of authenticity to the drab corridors and unforgiving parade grounds. It’s a world away from the gothic castles usually associated with Satanic rites, grounding the supernatural horror in a depressingly mundane reality. This contrast – the clean lines of military life versus the messy, ancient evil Stanley unearths – is central to the film's unsettling power.

Debugging Demons

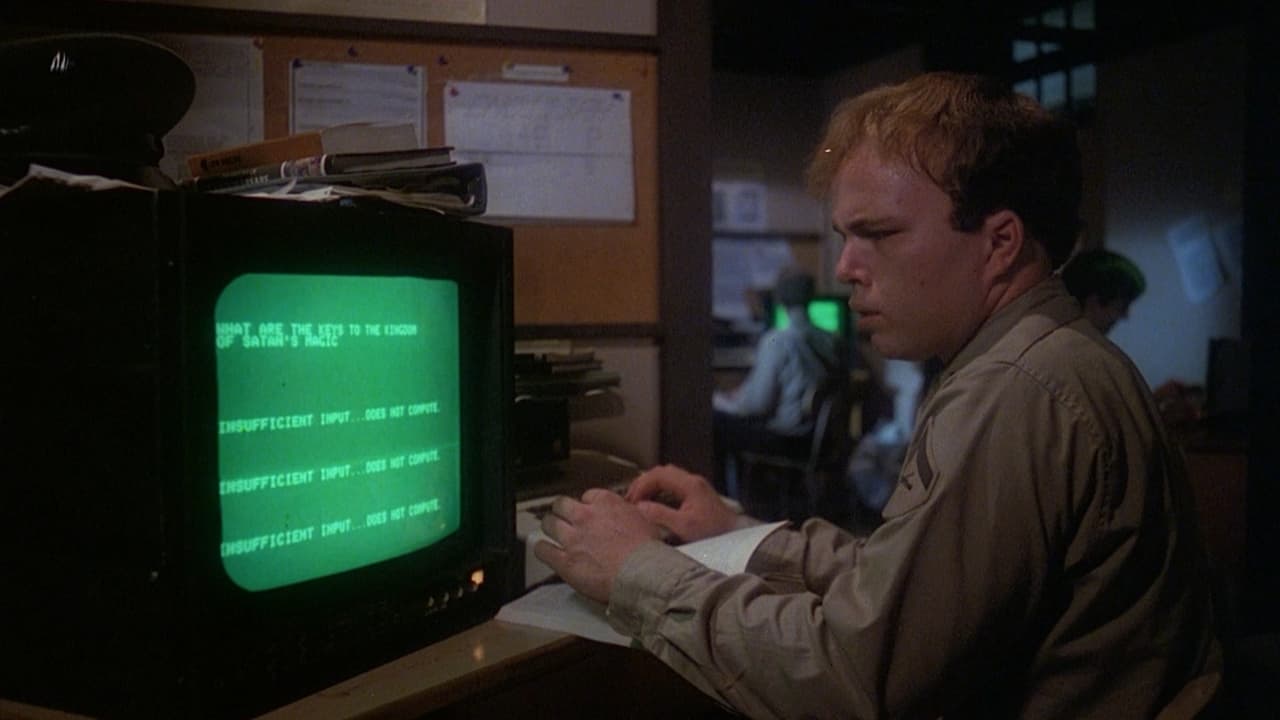

The real novelty, of course, is the computer. Stanley, a whiz kid ostracized for his brains, uses the academy’s primitive computer (an IMSAI 8080, a contemporary of the Altair 8800, for you tech history buffs) to translate Esteban’s demonic texts. The scenes of him typing commands, the slow crawl of translated text, the whirring of the floppy drive – it’s hilariously dated now, but back then, it represented the cutting edge merging with the occult. There's an inherent tension in watching this machine, designed for logic, become a conduit for pure, irrational evil. It taps into that early 80s anxiety about the mysterious power of computers, a theme explored more famously later in films like WarGames (1983). Fun fact: the complex "program" Stanley supposedly writes to perform the final ritual was likely just visual dressing, but convincing enough for the era.

Unholy Payback & VHS Infamy

Evilspeak isn’t a slow burn forever. Once Stanley starts performing the rituals dictated by the digital translations, things escalate. Minor hexes give way to genuine carnage. And then there’s the climax. Oh, that climax. Spoiler Alert! If you haven’t seen it, just know it involves demonic levitation, decapitation, and a truly unforgettable sequence with feral pigs summoned from the abyss to exact bloody revenge in the academy chapel. It’s messy, it’s graphic, and it’s utterly bonkers.

This finale, along with other moments of visceral gore, earned Evilspeak a notorious spot on the UK’s ‘video nasty’ list in the early 80s. Heavy cuts were demanded by the British Board of Film Classification (BBFC), and finding an uncut version on VHS became a badge of honor for hardcore horror collectors. The practical effects, while showing their age, possess a certain crude effectiveness. The pig sequence, reportedly achieved through a mix of real animals, puppetry, and clever editing, remains deeply unsettling precisely because it isn't slick CGI. It feels tangible, chaotic, and genuinely unpleasant – the kind of scene that stuck with you long after the tape ejected. Didn't that raw, practical gore feel somehow more real back then?

Lasting Static

While some performances outside of Howard feel a bit stiff (including R.G. Armstrong as the perpetually unimpressed Sarge), and the pacing occasionally drags before the explosive third act, Evilspeak holds a special place in the pantheon of early 80s horror. It’s a fascinating time capsule, blending the anxieties of the burgeoning computer age with age-old fears of demonic power, all wrapped up in a satisfyingly grim revenge tale. It perfectly captured that specific brand of gritty, mean-spirited horror that thrived on video store shelves.

Rating: 7/10

Evilspeak earns its score through Clint Howard's compelling lead performance, its uniquely unsettling blend of technology and Satanism, and an infamous climax that delivers the gory goods. While dated effects and uneven pacing hold it back from classic status, its grimy atmosphere and historical significance as a ‘video nasty’ make it essential viewing for cult horror aficionados and anyone who remembers when computers felt like arcane magic boxes capable of anything – even summoning hellish revenge. It’s a film that, much like its demonic computer program, executes its nasty payload with surprising effectiveness.