The powerlessness of being trapped, conscious but unable to move or speak, is a primal fear. But what if that trapped consciousness could lash out? What if paralysis wasn't the end, but the beginning of a different, unseen kind of terror? That's the chilling 'what if?' coiled at the heart of Richard Franklin's 1978 Australian creepfest, Patrick. Forget the frantic slashers that often dominated video store shelves; this was a different breed of horror, one that relied on stillness, suggestion, and the unnerving violation of personal space by an invisible force.

A Hospital of Whispers and Dread

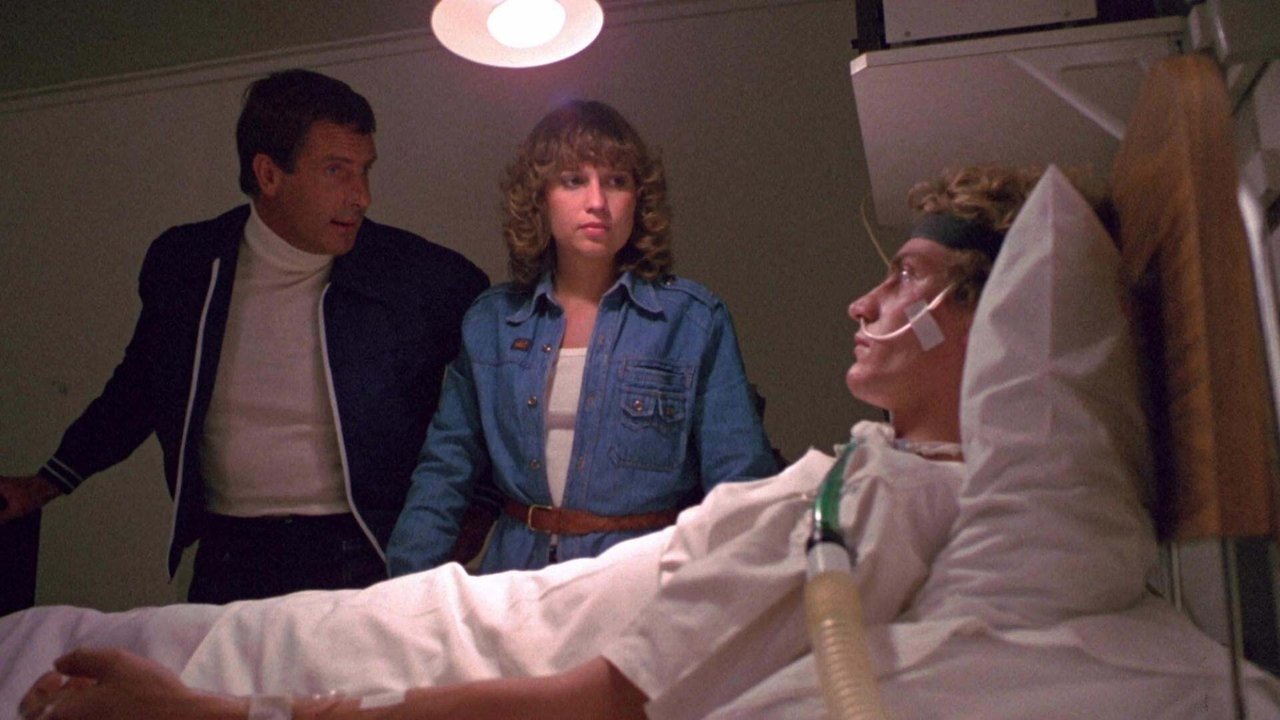

The film introduces us to Kathie (Susan Penhaligon), a nurse taking a new position at a somewhat isolated private hospital run by the severe Matron Cassidy (Julia Blake) and the ethically ambiguous Dr. Roget (Rod Mullinar). Among the patients is the titular Patrick (Robert Thompson), comatose for three years after murdering his mother and her lover. He lies inert, eyes wide open, a blank slate upon which Kathie initially projects sympathy. But soon, strange occurrences plague her life – objects move, messages appear, and a malevolent presence makes itself known. The chilling realization dawns: Patrick, though physically immobile, possesses terrifying psychokinetic abilities, fueled by obsession and directed squarely at Kathie. Franklin, a self-professed Hitchcock acolyte who would later, perhaps inevitably, direct Psycho II (1984), crafts an atmosphere thick with suspense rather than gore. The hospital corridors feel sterile yet menacing, the quiet punctuated by sudden, unnerving events.

The Unseen Hand

Patrick excels in making the mundane terrifying. A forcefully ejected stream of saliva – reportedly achieved with clever air pressure rigs off-camera – becomes an act of profound violation. A typewriter clattering out obsessive messages taps into a deep-seated unease. These aren't jump scares in the modern sense; they are calculated escalations of dread, showcasing the power of practical effects when used thoughtfully. Writer Everett De Roche, a key figure in the 'Ozploitation' wave (Long Weekend (1978), Razorback (1984)), understood that the fear here wasn't just about flying objects, but about the unseen intelligence guiding them, the absolute vulnerability of being targeted by someone you cannot reason with or even physically confront. The film makes you acutely aware of the fragility of control, the unease of knowing something is watching, acting, from the silent stillness of that hospital bed. Remember how genuinely shocking that final jolt felt, even after the slow burn? It was a masterclass in earning the scare.

Behind the Coma

Filmed on a modest budget (around $400,000 AUD), Patrick became a significant international success for the burgeoning Australian film industry. Its journey wasn't without bumps, however. American distributors, perhaps unsure how to market its unique blend of psychological horror and psychic phenomena, notoriously recut and dubbed the film for its US release, softening some edges and altering dialogue – a version many of us likely first encountered on worn-out VHS tapes, unaware of the original's slightly sharper tone. Finding an original Aussie cut back then felt like uncovering a hidden treasure. The casting of Robert Thompson as Patrick was crucial; his near-total immobility throughout the film, save for those unnervingly wide eyes, creates a truly unsettling focal point. He becomes a canvas for our own fears about the unknown depths of the human mind. Susan Penhaligon carries the film admirably, portraying Kathie's journey from compassionate caregiver to terrified victim with believable vulnerability.

A Slow Burn with Lasting Chill

While some might find the pacing deliberate by today's standards, Patrick’s slow-burn tension is precisely its strength. It allows the psychological implications of the scenario to seep under your skin. It’s less about overt shocks and more about sustained creepiness, the constant awareness of Patrick's unseen influence invading Kathie's life. The film even spawned an infamous, unrelated Italian exploitation sequel, Patrick Still Lives (1980), a testament, perhaps, to the original's memorable premise, even if the follow-up veered into far grislier territory. Doesn't the core concept – the immobile tormentor – still feel uniquely disturbing?

Patrick remains a standout example of 70s psychological horror and a key film in Australia's genre output. It trades visceral shocks for a pervasive sense of unease, leveraging its central terrifying concept and Richard Franklin's controlled direction to maximum effect. While certain elements might feel dated, the core dread it taps into – the fear of the unseen, the violation of personal space, the horror of a mind trapped but powerful – resonates long after the credits roll and the VCR clicks off. It’s a film that proves stillness can be far more frightening than frenzy.

VHS Heaven Rating: 8/10

Rating Justification: Patrick earns its 8 for its highly original and genuinely unsettling premise, its masterful build-up of atmospheric dread, Susan Penhaligon's strong central performance, and its clever use of practical effects to generate psychological chills rather than gore. It’s a cornerstone of Ozploitation and a masterclass in slow-burn tension. Points are only slightly deducted for pacing that might test some modern viewers and the slightly less impactful (though infamous) US recut many experienced first.

Final Thought: Decades later, the image of Patrick, eyes wide open in his hospital bed, remains a potent symbol of dormant, unknowable terror – a quiet nightmare captured on magnetic tape.