It begins with a sickly yellow fog rolling across a lonely country road. A school bus, carrying five children home, vanishes into the toxic haze. When it emerges, silence reigns. The driver is dead, slumped over the wheel. The children? They stumble out, seemingly unharmed, but unnervingly quiet, their eyes vacant, their fingernails blackened. They are no longer children. They are something else, carriers of an instant, lethal contagion transmitted by the most innocent of gestures: a hug. Welcome to the quiet nightmare of The Children (1980).

### A Foggy Descent into Fear

This isn't a film that assaults you with constant noise or jump scares. Instead, The Children cultivates a pervasive sense of wrongness. Director Max Kalmanowicz allows the isolation of the snowy New England setting (primarily Sharon, Connecticut, its quiet streets lending an authentic chill) to seep into the frame. The story unfolds with a grim deliberateness. When the children arrive at their homes, their parents are overjoyed, oblivious to the vacant stares and the dark smudges under their nails. The first kill, delivered via an embrace, is shocking in its mundane domesticity. There’s no monstrous transformation, just a silent, deadly touch, leaving behind a victim seemingly burned from the inside out. It’s this low-key, almost procedural approach to the horror that gives the film its unique, unsettling power, a feeling perfectly suited to late-night viewing on a grainy VHS tape.

### The Little Terrors

What makes the titular children so effective isn't elaborate makeup or complex effects – it’s their chilling passivity. They don't snarl or chase; they simply approach, arms outstretched, their faces blank masks. Their method of attack – the deadly hug – weaponizes the very symbol of childhood affection and trust, turning it into an instrument of horrifying death. It’s a simple, potent concept that taps into a primal unease. Reportedly, some of the young actors were local kids, adding another layer of unsettling authenticity to their performances. They aren't "acting" monstrous in an overt way; they are simply present, radiating a cold, alien menace. Doesn't that quiet stillness make them somehow creepier than your average slasher villain? The practical effect of the blackened fingernails and the post-mortem "burn" makeup is rudimentary by today's standards, but possesses a tactile grunginess that felt disturbingly real on flickering CRT screens.

### Adults Under Siege

Caught in this bizarre, escalating nightmare are the bewildered adults, led by Sheriff Billy Hart (Gil Rogers) and concerned father John Hansen (Martin Shakar). Their slow realization of the truth – that these aren't their kids anymore, but biological time bombs – forms the dramatic core. The performances are earnest, reflecting the confusion and dawning horror of ordinary people facing an inexplicable threat. A standout, perhaps unexpectedly, is Gale Garnett as Cathy Freemont. Garnett, primarily known for her 1964 Grammy-winning folk hit "We'll Sing in the Sunshine," brings a grounded intensity to her role as one of the terrified parents. Her presence adds a touch of unexpected pedigree to this low-budget ($250,000 estimated budget) affair, a reminder of the eclectic casting often found in genre films of the era. The script, co-written by Carlton J. Albright (who would later give us the uniquely bizarre Luther the Geek), doesn't always give the adults the sharpest dialogue, but their fear feels genuine.

### Low-Budget Dread Done Right

Let's be clear: The Children is undeniably a product of its time and budget. The pacing can feel uneven, some line readings are a bit stiff, and the explanation for the toxic cloud is pure B-movie science. Yet, it transcends its limitations through sheer creepy conviction. The filmmakers understood that the idea of children turned into silent, remorseless killers was inherently disturbing. They lean into the atmosphere, the desolate locations, and the unsettling quietness of the threat. One particularly effective sequence involves the adults realizing the horrifying truth about how the "infection" spreads, leading to a grim, necessary defense strategy that feels both logical and deeply taboo. It’s moments like these, delivered without fanfare, that stick with you. The film also holds a unique place in the "killer kid" subgenre, opting for a pseudo-scientific, almost zombie-like threat rather than demonic possession or inherent evil, setting it apart from contemporaries like The Omen or even Village of the Damned.

### Lasting Chill Factor

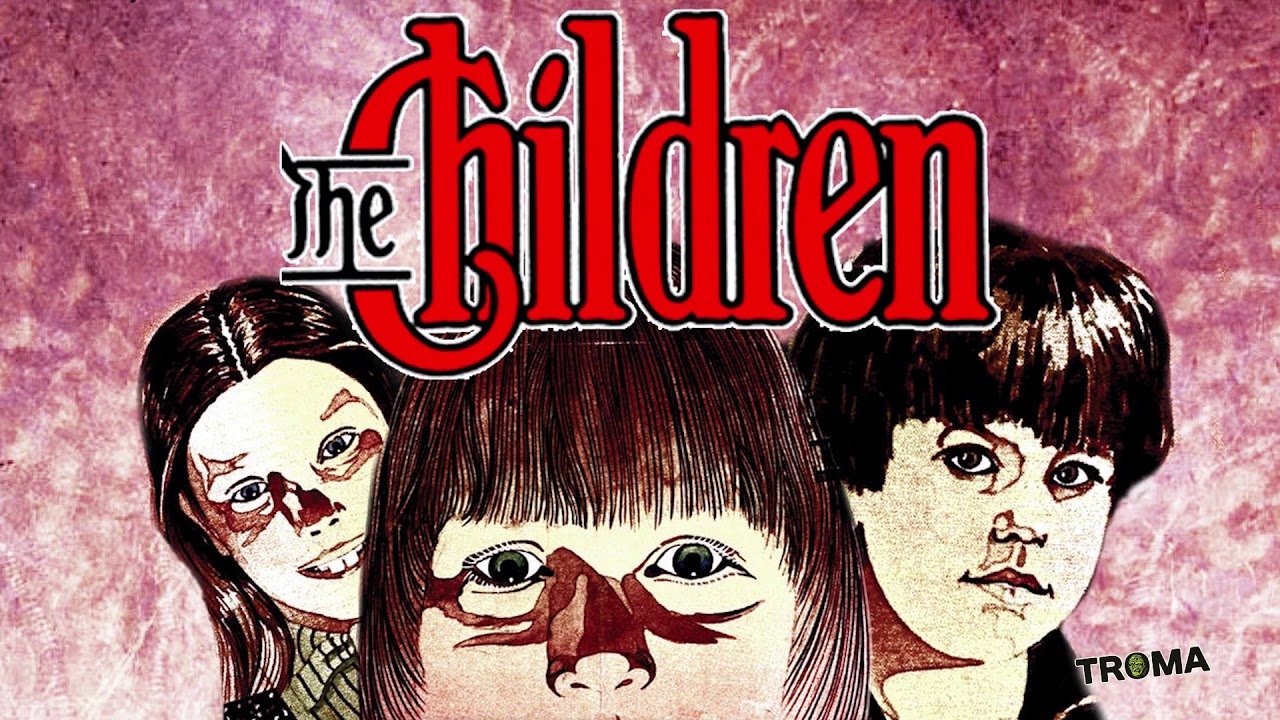

The Children might not be polished horror, but it’s effective horror. It’s the kind of film you'd discover late at night on cable or pick up from the video store based on its unsettling cover art, only to find yourself genuinely creeped out by its quiet menace and disturbing central concept. It doesn't rely on gore, but on a pervasive atmosphere of dread and the violation of innocence.

VHS Heaven Rating: 6/10

Justification: The score reflects the film's undeniable effectiveness in creating a creepy atmosphere and delivering on its unsettling premise, especially considering its low budget. It earns points for its unique "killer kid" angle and memorable, chilling moments. However, it loses points for pacing issues, some uneven performances, and production limitations characteristic of its budget and era. It's a flawed gem, but a gem nonetheless for fans of gritty, atmospheric 80s horror.

Final Thought: Decades later, the image of those silent children with their blackened nails and outstretched arms remains genuinely unnerving. It’s a testament to the power of a simple, chilling idea executed with conviction, a perfect example of the creepy discoveries that awaited us in the aisles of the local video store.