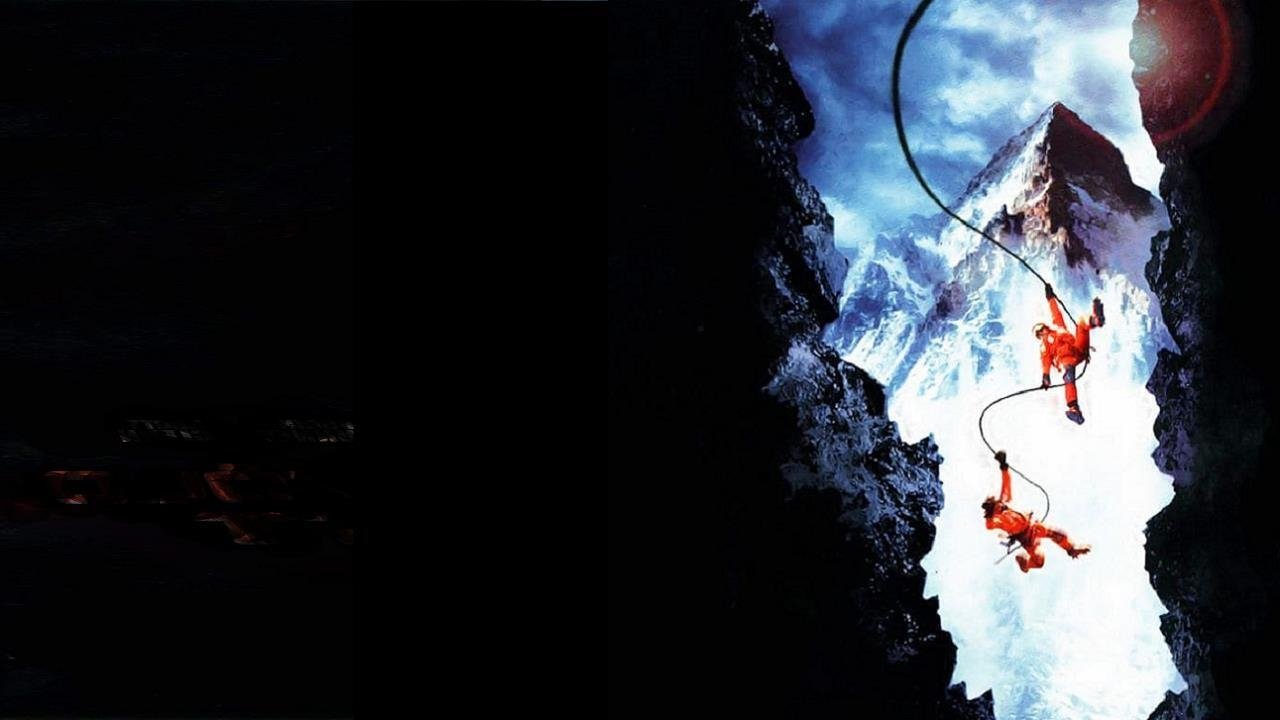

The air thins. Ice crystals bite at exposed skin. Below, a seemingly infinite drop into oblivion. Some films build dread through shadow and suggestion; Martin Campbell’s Vertical Limit (2000) opts for the more primal fear of gravity, exposure, and the crushing indifference of the world’s second-highest peak. It plunges you onto the unforgiving slopes of K2, where every breath is earned and every step courts disaster, delivering a high-altitude thriller that feels like frostbite for the nerves. Forget subtlety; this is a film that straps unstable nitroglycerin to its heroes and dares you not to flinch.

Released right at the turn of the millennium, Vertical Limit arrived when disaster movies were enjoying a slick, CGI-enhanced resurgence. While perhaps lacking the character depth of predecessors like Alive (1993), it compensates with relentless, often ludicrously staged, action sequences. The setup is pure Hollywood peril: estranged siblings Peter (Chris O’Donnell) and Annie (Robin Tunney) are reunited during a K2 expedition led by billionaire Elliot Vaughn (Bill Paxton). When an avalanche traps Annie, Vaughn, and veteran climber Tom McLaren (Nicholas Lea) in an ice cave above the "death zone," Peter must assemble a ragtag rescue team for an impossible ascent against a ticking clock, dictated by the dwindling oxygen and the threat of pulmonary edema.

### Danger Above 8,000 Meters

Martin Campbell, already proven with the high-stakes action of GoldenEye (1995) and The Mask of Zorro (1998), directs with a focus on momentum and visceral impact. The film rarely pauses for breath, hurtling from one crisis to the next. Avalanches cascade with digital fury (impressive for its time, if showing its age now), ice axes become desperate lifelines, and crevasses yawn open like hungry mouths. Campbell understands how to frame the immense scale of the mountain – primarily shot in New Zealand's Southern Alps and the Canadian Rockies, standing in for the Karakoram Range – making the human figures seem desperately small and fragile against the towering peaks. The cinematography captures both the stark beauty and the lethal hostility of the environment.

The core conceit – using volatile nitroglycerin canisters to blast open the ice cave – adds a wonderfully absurd layer of tension. Each jolt, each slip, threatens to vaporize the rescuers. It’s a premise that borders on the ridiculous, yet the film commits to it wholeheartedly. Reportedly, ensuring the safety around even the prop explosives during the frantic action scenes required meticulous coordination from the stunt teams, led by veteran coordinator Simon Crane (Saving Private Ryan, Titanic). It’s this commitment to over-the-top, tangible danger that gives Vertical Limit its specific, enduring charm.

### Faces in the Frost

While the plot mechanics drive the film, the cast injects some necessary humanity. Chris O’Donnell, then best known as Robin in the Schumacher Batman films, carries the lead effectively as the determined, guilt-ridden brother. Robin Tunney brings vulnerability and resilience to Annie. But it’s often the supporting players who steal the show. The late, great Bill Paxton is magnetic as the ambitious, morally ambiguous billionaire, chewing scenery with infectious gusto. And Scott Glenn, as the enigmatic, almost mythical mountaineer Montgomery Wick, provides a grounding presence of grizzled wisdom and quiet intensity. His character supposedly draws inspiration from legendary climbers, adding a touch of real-world grit to the Hollywood fantasy. There's a story that Glenn, a former Marine, embraced the physical demands, adding to Wick's authentic feel.

The script, credited to Robert King (who would later create The Good Wife) and Terry Hayes (Mad Max 2: The Road Warrior), isn't aiming for complex character studies. Dialogue often serves to explain the next impending disaster or reiterate the stakes. The emotional core revolves around the fractured sibling relationship and themes of guilt, redemption, and survival against impossible odds. It’s effective, if not particularly deep, providing just enough motivation to care about who makes it down the mountain alive.

### Retro Thrills and Chills

Watching Vertical Limit today is a fascinating snapshot of turn-of-the-century blockbuster filmmaking. Its $75 million budget (around $130 million today) is evident in the spectacular set pieces and location work. It delivered thrills and became a solid box office success, pulling in over $215 million worldwide. The practical stunt work, particularly the climbing sequences and desperate traverses, still holds up remarkably well, possessing a weight and reality that pure CGI often lacks. Remember how convincing those ice axe saves looked on the big screen (or your trusty CRT)? Doesn't that sheer drop still give you a touch of vertigo?

Sure, some elements feel dated – the early-2000s techno-infused elements in James Newton Howard’s otherwise effective score, the slightly clunky moments of digital augmentation. And yes, the plot requires a significant suspension of disbelief regarding mountaineering realities and the behaviour of nitroglycerin at altitude. But does it entertain? Absolutely. It taps into that primal fear of falling, of being trapped, of nature’s overwhelming power. I distinctly remember renting this one, the bright green spine of the Columbia TriStar VHS case promising exactly the kind of large-scale adventure it delivered. It was pure escapism, designed to make your palms sweat.

Rating: 7/10

Vertical Limit doesn't rewrite the disaster movie playbook, nor does it offer profound insights into the human condition. What it does, exceptionally well, is deliver a relentless, high-altitude thrill ride powered by spectacular stunts, Martin Campbell's muscular direction, and a scene-stealing turn from Bill Paxton. It leans into its B-movie premise with A-list production values, resulting in a film that’s far more entertaining than it perhaps has any right to be. For fans of pure, unadulterated action spectacle from the Y2K era, it remains a breathless, if slightly bonkers, ascent worth taking. It’s a reminder of a time when blockbusters could be gloriously, unashamedly straightforward in their quest to simply thrill us.