The biting cold of the Alaskan wilderness seeps through the screen long before the real trouble starts. There's an initial, deceptive beauty – vast landscapes, crisp air – but underneath it, something predatory stirs. Not just in the unseen corners of the forest, but in the clipped, loaded exchanges between billionaire Charles Morse (Anthony Hopkins) and charismatic fashion photographer Bob Green (Alec Baldwin). 1997's The Edge wasn't just another survival thriller; it was a David Mamet-penned chess match played out against a backdrop of primal terror, the kind of film that felt perfectly suited to the late-night quiet of a flickering CRT screen.

Whispers Before the Roar

The setup is deceptively simple: Charles, a man whose wealth is matched only by his encyclopedic knowledge, joins his much younger supermodel wife, Mickey (Elle Macpherson, embodying the era's high fashion), on a remote photo shoot helmed by the confident Bob. The tension crackles immediately. Charles suspects Bob and Mickey are having an affair. Bob seems wary, perhaps slightly contemptuous, of Charles's quiet intellect. It's classic Mamet – sharp, minimalist dialogue hinting at vast reservoirs of distrust and unspoken rivalry. We're trapped with these characters in an emotional pressure cooker even before their small plane succumbs to a bird strike, plunging them violently into the unforgiving wilderness alongside Bob's assistant, Stephen (Harold Perrineau, years before he found himself similarly stranded on Lost).

When Nature Bites Back

The plane crash itself is a brutal, effective sequence, a stark reminder of the practical stunt work and effects that defined the era. Suddenly, the interpersonal drama is dwarfed by the immediate, life-or-death struggle against the elements. Director Lee Tamahori, who had previously stunned audiences with the raw intensity of Once Were Warriors (1994), proves adept at capturing both the majestic indifference of the landscape (shot beautifully, if arduously, in the wilds of Alberta, Canada) and the sudden, heart-stopping violence that lurks within it. And then there's the bear.

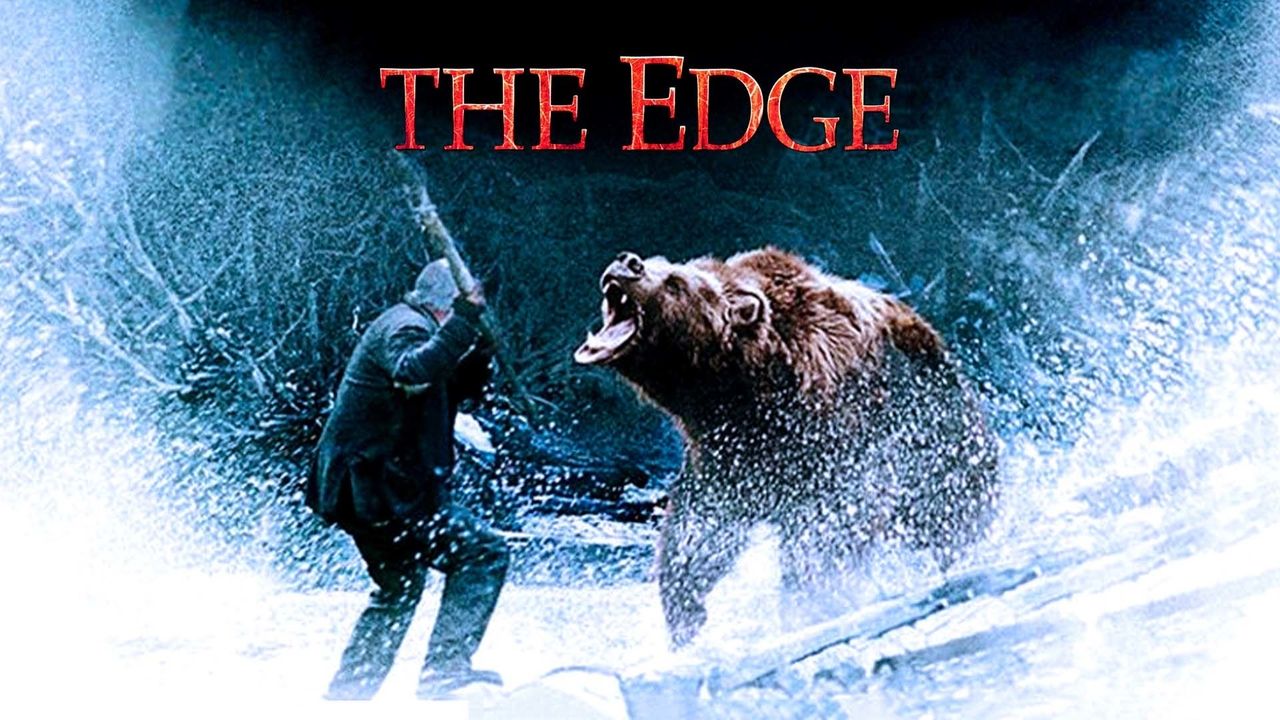

Not just any bear, mind you. This is Bart the Bear, the 1,500-pound Kodiak behemoth trained by the legendary Doug Seus, arguably delivering one of the most terrifying and convincing animal performances ever captured on film. Forget CGI creations; Bart's sheer physical presence, his guttural roars, the terrifying intelligence in his eyes – it’s viscerally real. Remember seeing this on VHS? The sheer scale of Bart felt overwhelming, a force of nature made terrifyingly tangible. There are stories that Anthony Hopkins, ever the dedicated professional who reportedly immersed himself in survival manuals for the role, formed a respectful bond with Bart on set, crucial for the scenes requiring close proximity. This wasn't just a monster; it was a character, embodying the raw, deadly power of the wild these men had foolishly stumbled into. Doesn't that bear still feel unnervingly real, even today?

Survival of the Smartest (and Meanest?)

What elevates The Edge beyond a simple creature feature is Mamet's script. As the survivors face starvation, freezing temperatures, and the relentless pursuit of the bear, Charles's bookish knowledge becomes their most potent weapon. "What one man can do, another can do," he states, a mantra that drives him to turn scraps of knowledge into practical survival skills. The film brilliantly contrasts Charles's methodical, analytical approach with Bob's more impulsive, physically capable nature.

The simmering mistrust between them never truly dissipates; it merely shifts focus. The bear becomes the immediate threat, but the question always hangs in the air: can they rely on each other? Will the tensions from their civilized lives explode now that the rules have changed? Mamet’s dialogue, though sometimes criticized for being overly stylized for men fighting for their lives ("I'm gonna kill the bear!"), provides a fascinating layer. It’s about asserting dominance, about the primal urge to conquer, whether the target is a rival or a force of nature. The famous line Charles delivers – "You know, most people lost in the wild, they die of shame" – cuts deep, speaking volumes about ego and the will to live.

Crafted Dread

Tamahori’s direction, coupled with Donald McAlpine’s stark cinematography, emphasizes the isolation and the constant, gnawing tension. The vast, snowy landscapes feel both beautiful and menacing. Every snapped twig, every rustle in the undergrowth feels amplified. And then there's the score by the late, great Jerry Goldsmith (Alien, Poltergeist). It’s a magnificent piece of work – grand and sweeping when capturing the scale of the wilderness, but capable of dropping into genuinely unnerving, percussive dread during moments of pursuit or confrontation. It’s the kind of score that burrows under your skin. Despite its pedigree, the film was something of a box office disappointment, making around $43 million worldwide against its $30 million budget. Perhaps its blend of intellectual thriller and brutal survival action was a tougher sell than expected back in '97.

Hopkins and Baldwin: A Primal Duel

The film truly rests on the shoulders of its two leads. Hopkins, embodying quiet intelligence masking a steely resolve, is utterly compelling. You believe every moment of his transformation from billionaire intellectual to resourceful survivor. Alec Baldwin matches him stride for stride, navigating Bob’s complex mix of charm, arrogance, and desperation. Their shifting dynamic – from suspicion to grudging reliance and back again – forms the psychological core of the film. It’s a masterclass in character-driven tension, played out against the most extreme circumstances.

***

The Edge remains a potent, intelligent thriller that feels distinctly of its time, yet timeless in its themes of survival, rivalry, and the stripping away of civilized veneers. It blended cerebral dialogue with visceral action and featured one of cinema's most memorable animal antagonists. Watching it again evokes that specific late-90s feeling – a well-crafted, star-driven thriller that wasn't afraid to be brutal and thoughtful in equal measure. It’s a sharp, chilling journey into the wild, both outside and within.

Rating: 8/10

Final Thought: More than just a bear-attack movie, The Edge is a gripping examination of masculinity and intellect under pressure, anchored by two powerhouse performances and a truly unforgettable ursine co-star. It’s the kind of lean, mean, smartly written thriller that still delivers a satisfyingly chilling bite.