Here we go, another spin in the VCR for a film that perhaps didn't dominate the Blockbuster shelves but certainly left a mark on those who sought it out. This time, we're venturing to late 90s South Korea with Jung Ji-woo's devastating 1999 debut feature, Happy End. And let me tell you, the title hangs heavy with an irony so thick you could cut it with the edge of a worn VHS slipcase.

An Unsettling Quiet Before the Storm

What strikes you first about Happy End isn't explosive action or dazzling effects, but a pervasive, almost suffocating sense of quiet desperation. The film opens not with a bang, but with the muted hum of domesticity strained to its breaking point. We meet Choi Bora (Jeon Do-yeon), a successful career woman increasingly detached from her home life, and her husband, Seo Min-ki (Choi Min-sik), recently laid off from his banking job during the harsh realities of the late 90s Asian financial crisis (an omnipresent, though rarely explicitly stated, pressure cooker). He's now adrift, caring for their infant child, reading romance novels, and simmering in a potent brew of emasculation and unspoken resentment. It’s a scenario uncomfortably familiar, perhaps, mirroring anxieties many faced then, and still do. Doesn't that loss of identity, that feeling of being unmoored by economic forces beyond one's control, resonate across decades?

The Triangle's Jagged Edges

Into this fragile ecosystem steps Kim Il-beom (Joo Jin-mo), Bora's passionate ex-lover. Their rekindled affair isn't depicted as a simple escape, but as a volatile chemical reaction – a desperate grasp for feeling, for affirmation, perhaps even for a past self, set against the sterile backdrop of Bora's increasingly transactional life. Jeon Do-yeon, even early in her illustrious career (which would later include a Best Actress win at Cannes for Secret Sunshine (2007)), is utterly fearless here. She doesn't ask us to like Bora, but demands we understand her complex, often contradictory, motivations. Her weariness, her flashes of desperate passion, her calculated compartmentalization – it's a portrait etched with uncomfortable truths about desire and dissatisfaction.

And then there's Choi Min-sik. Seeing him here, pre-Oldboy (2003) fame that would make him an international icon, is fascinating. His Min-ki is a study in implosion. The camera often lingers on his face, seemingly placid but betraying micro-shifts of hurt, suspicion, and slowly curdling rage. It's not the explosive Choi we might associate with later roles, but a deeply internalised performance where the silence speaks volumes. His passive-aggression, his fumbling attempts to reconnect, his eventual chilling discoveries – it’s a masterclass in conveying a man unraveling from the inside out. Joo Jin-mo, too, effectively embodies the allure and inherent danger of the past, the illicit thrill that masks a deeper emptiness.

Crafting Claustrophobia

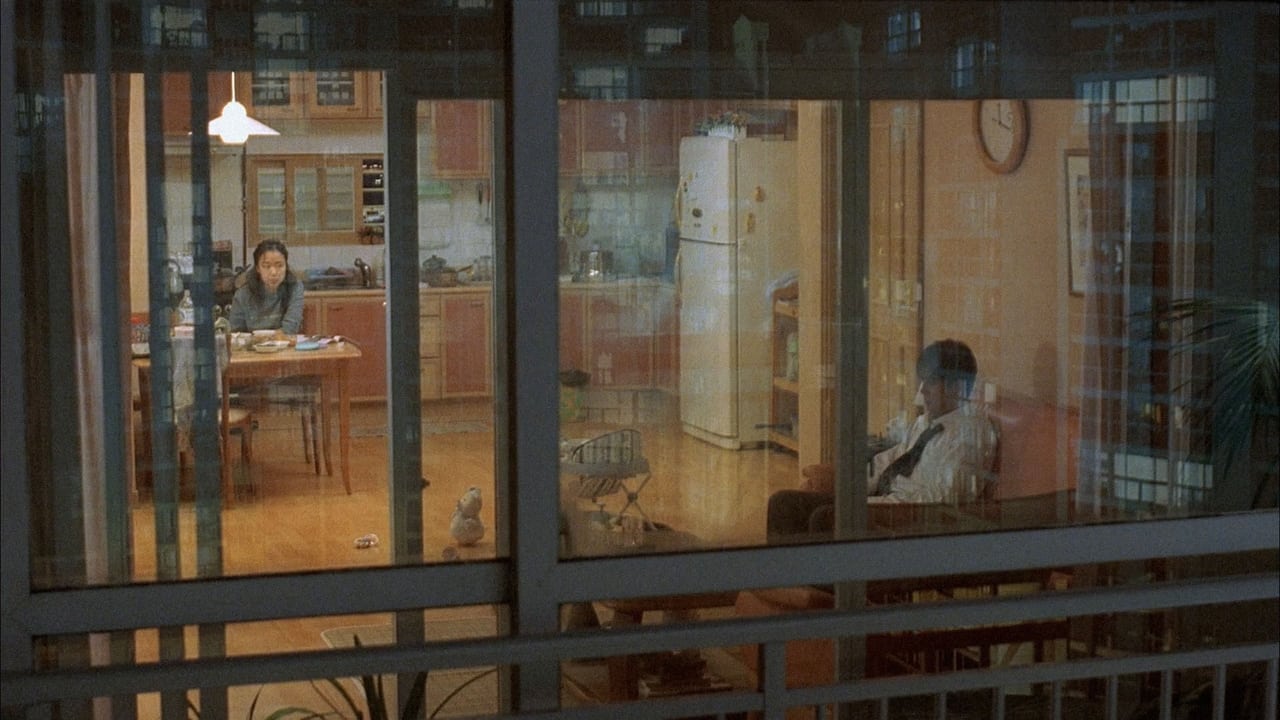

Director Jung Ji-woo, in his feature debut, demonstrates remarkable control. There's a deliberate, almost voyeuristic quality to the filmmaking. The camera often observes from doorways, through windows, mirroring Min-ki's growing suspicion. The colour palette feels muted, reflecting the emotional landscape of the characters. There are no flashy directorial tricks; instead, the focus is on atmosphere and performance, allowing the tension to build organically, inexorably. Reportedly, the film stirred considerable controversy in South Korea upon release due to its explicit scenes and bleak portrayal of marriage and infidelity, pushing boundaries in what was becoming the fertile ground of the Korean New Wave. It felt raw, unflinching, a stark departure from more sanitized mainstream fare. Perhaps it was precisely this honesty, this willingness to gaze into the abyss of ordinary lives pushed to extremes, that made it resonate.

I remember renting films like this back in the day, perhaps not on VHS but certainly on early DVD imports from labels like Tartan Asia Extreme. Discovering contemporary Korean cinema felt like uncovering a hidden treasure trove – films that were sophisticated, daring, and emotionally potent in ways that often felt lacking elsewhere. Happy End was definitely one of those early, impactful discoveries.

The Inevitable Reckoning

(Minor Spoilers Ahead – Tread Carefully!)

The film's title becomes almost unbearably poignant as the narrative progresses. There's a grim inevitability to the way the strands of betrayal, jealousy, and economic despair tighten. Min-ki's discovery of the affair isn't a sudden explosion but a slow, dawning horror, meticulously pieced together. The film refuses easy answers or catharsis. It forces us to confront the devastating consequences when communication breaks down, when societal pressures mount, and when quiet desperation finally finds a violent outlet. The climax is shocking, not merely for its brutality, but for its chillingly methodical execution, born from that deeply unsettling performance by Choi Min-sik. What does it take for an ordinary person to be pushed to such an extraordinary, terrible act? The film leaves that question hanging heavy in the air.

(Spoilers End)

Lingering Unease

Happy End isn't a comfortable watch. It’s not a film you pop in for light entertainment. It’s a meticulously crafted psychological drama that burrows under your skin and stays there. Its power lies in its unflinching realism, the superb, nuanced performances from its leads, and its exploration of dark emotional territory often shied away from. It examines the fractures in modern relationships, the weight of expectations, and the destructive potential lurking beneath the surface of seemingly ordinary lives.

Rating: 8.5/10

This score reflects the film's exceptional craft, its powerhouse performances (especially from Jeon Do-yeon and Choi Min-sik), and its daring, mature exploration of complex themes. It's a challenging but rewarding piece of late 90s cinema that showcased the burgeoning power of the Korean New Wave. It loses a fraction for its almost unrelenting bleakness, which might make it difficult for some, but its artistic merit and psychological depth are undeniable.

It’s a potent reminder that sometimes, the most devastating stories are the quietest ones, and that the label on the box rarely tells the whole story of the tangled emotions waiting inside. A haunting entry from the cusp of a new millennium in cinema.