It starts not with a bang, but with a slow burn, the Earth turning below as Bob Marley sings "Burnin' and Lootin'". Then, darkness, and a date: April 6th, 1993. Newsreel footage, stark and real, of clashes. This isn't the Paris of postcards; this is the pressure cooker on the outskirts, and Mathieu Kassovitz's La Haine (Hate) drops you right into the middle of it, unfiltered, unforgettable. Pulling this tape from its sleeve back in the day felt different. Even through the grainy resolution of a CRT, the monochrome visuals pulsed with an energy that was immediate, vital, and frankly, a little terrifying. It felt less like a movie rental and more like intercepting a raw transmission from a world away.

A Day Like Any Other, Until It Isn't

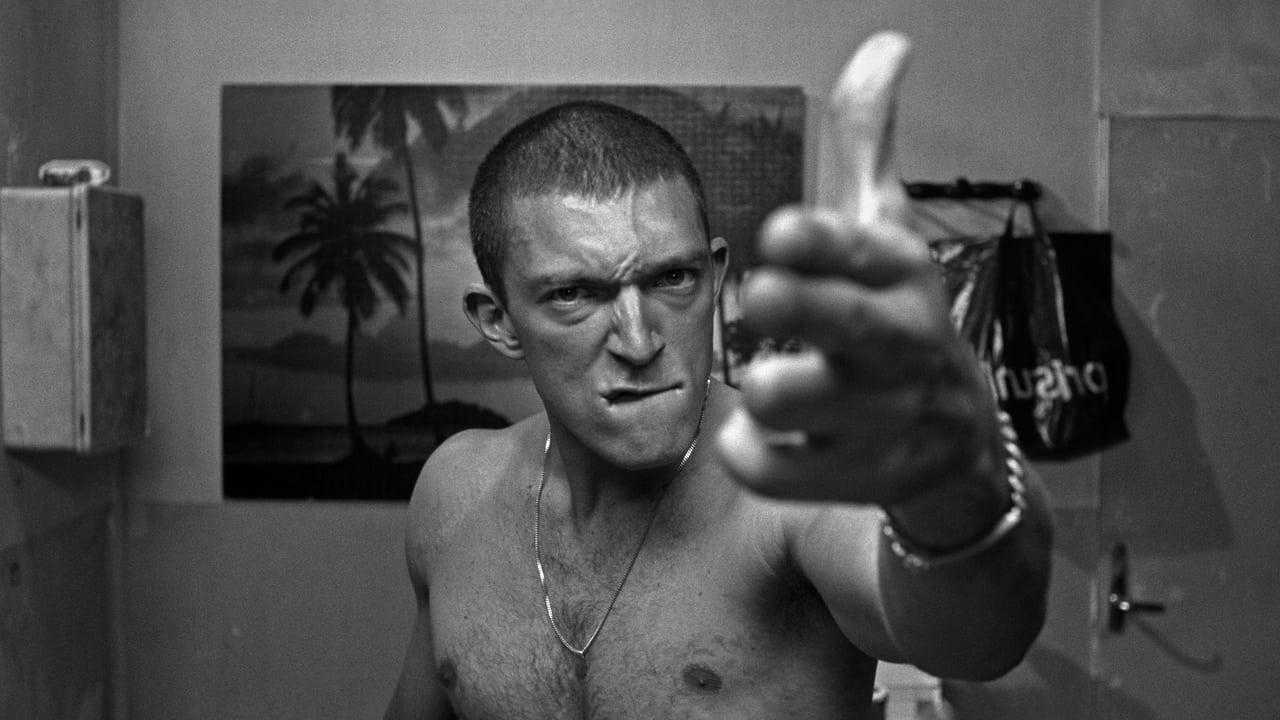

The premise is deceptively simple: we follow three friends – Vinz (Vincent Cassel), Hubert (Hubert Koundé), and Saïd (Saïd Taghmaoui) – over roughly 24 hours in the wake of riots sparked by the brutal police beating of their friend, Abdel. Vinz, Jewish, volatile, and seething with misplaced rage, has found a policeman's lost gun and sees it as his ticket to respect, maybe revenge. Hubert, Afro-French, a boxer whose gym was destroyed in the riots, carries the weight of weary pragmatism, dreaming of escape but anchored by circumstance. Saïd, of North African descent, acts as the often-comedic, observant connective tissue between the two extremes. Their day unfolds not in grand dramatic arcs, but in a series of encounters, observations, and escalating tensions, mirroring the simmering unrest of their environment.

The Fire Within: Performances Forged in Reality

What elevates La Haine beyond a mere social document is the electric chemistry and fierce authenticity of its central trio. Vincent Cassel, in the role that truly launched him internationally (before becoming a familiar face in films like Ocean's Twelve (2004) and Black Swan (2010)), is mesmerizing as Vinz. He’s a powder keg, channeling Travis Bickle in the mirror one moment, revealing flashes of boyish vulnerability the next. His anger feels both terrifyingly real and tragically misdirected. Hubert Koundé provides the film's weary soul. His quiet intensity speaks volumes; you feel the crushing weight of his desire for something better clashing with the grim reality he can't seem to shake. And Saïd Taghmaoui, who also co-wrote parts of the script based on his own experiences, brings a restless energy and street-smart wit that grounds the film, his perspective often mirroring our own as viewers dropped into this volatile landscape. Their interactions – the banter, the arguments, the shared moments of boredom and frustration – feel utterly lived-in. There's a palpable sense that these weren't just actors playing roles, but young men channeling the anxieties and anger of a generation. Kassovitz famously encouraged improvisation, letting their natural dynamic shape many scenes, a choice that bleeds authenticity onto the screen.

Black and White, But Far From Simple

Mathieu Kassovitz, who was only 27 when he directed this bombshell (and snagged the Best Director award at Cannes for it), makes a deliberate, powerful choice to shoot in black and white. This isn't just an aesthetic flourish; it strips away distractions, emphasizing the starkness of the architecture, the grit of the streets, and the raw emotions on the actors' faces. It unifies the disparate racial backgrounds of the main characters under the common banner of marginalization, painting their world in shades of grey, literally and metaphorically. The cinematography is constantly inventive – think of that astonishing, fluid helicopter shot drifting over the estate as DJ Cut Killer blasts sound across the courtyard, a moment of defiant community expression. Kassovitz uses the camera not just to observe, but to immerse, making the banlieue itself a character – oppressive, isolating, yet fiercely alive.

Echoes in the Concrete

The film was famously inspired by the real-life killing of a young Zairian man, Makome M'Bowole, by police in 1993. Kassovitz started writing the script the day it happened. This grounding in reality lends La Haine an undeniable urgency. It wasn't just a movie; it was a Molotov cocktail thrown into the lap of polite French society, sparking intense debate and even prompting the Prime Minister at the time, Alain Juppé, to arrange a special screening for his cabinet – reportedly, some ministers were deeply uncomfortable. Watching it on VHS, perhaps thousands of miles away, you still felt that shockwave. It served as a potent counter-narrative to the glossy Hollywood exports that usually filled the shelves of the local video store. Its relatively modest budget (around $2.6 million USD) yielded a cultural impact far exceeding its cost, proving that powerful storytelling doesn't always need blockbuster resources.

The Inescapable Question

La Haine isn't an easy watch, nor should it be. It forces us to confront uncomfortable truths about inequality, prejudice, and the cyclical nature of violence. The famous line, repeated throughout – "It's about a society falling. On the way down, it keeps telling itself: 'So far so good... So far so good... So far so good.' How you fall doesn't matter. It's how you land." – hangs heavy long after the credits roll. Does Vinz’s anger solve anything? Can Hubert truly escape the gravity of his environment? What responsibility does society bear for creating these pressure cookers? The film offers no easy answers, opting instead for a portrait that is both specific to its time and place, yet depressingly universal in its themes.

Rating: 9.5/10

This score reflects the film's masterful direction, phenomenal performances, stark visual power, and enduring social relevance. La Haine is technically brilliant, emotionally shattering, and intellectually provocative. It loses perhaps half a point only because its bleakness can feel almost overwhelming, offering little respite. Yet, its power lies precisely in that unflinching gaze. It’s a landmark of 90s cinema, a vital piece of social commentary captured with artistic fury.

Watching La Haine again, decades later, the grain of the non-existent VHS tape feels almost metaphorical. It’s a film that remains raw, urgent, and essential – a stark reminder that the fall might be long, but the landing is inevitable. How we choose to face it, both then and now, remains the burning question.