There are films that nestle comfortably into memory, like a favorite worn armchair. And then there are films like Mathieu Kassovitz's Assassin(s) (1997), which feel more like finding a shard of glass embedded in that same chair years later – sharp, unsettling, and demanding attention. Following his explosive arrival with the critically acclaimed La Haine (1995), the weight of expectation on Kassovitz must have been immense. What he delivered wasn't a crowd-pleaser, but a bleak, methodical, and deeply uncomfortable examination of violence, mentorship, and media saturation that left audiences reeling and critics sharply divided, famously drawing boos at its Cannes Film Festival premiere. Renting this back in the day, perhaps nestled between a glossy Hollywood thriller and a familiar comedy on the video store shelf, was to invite something far colder and more confrontational into your living room.

An Unsettling Apprenticeship

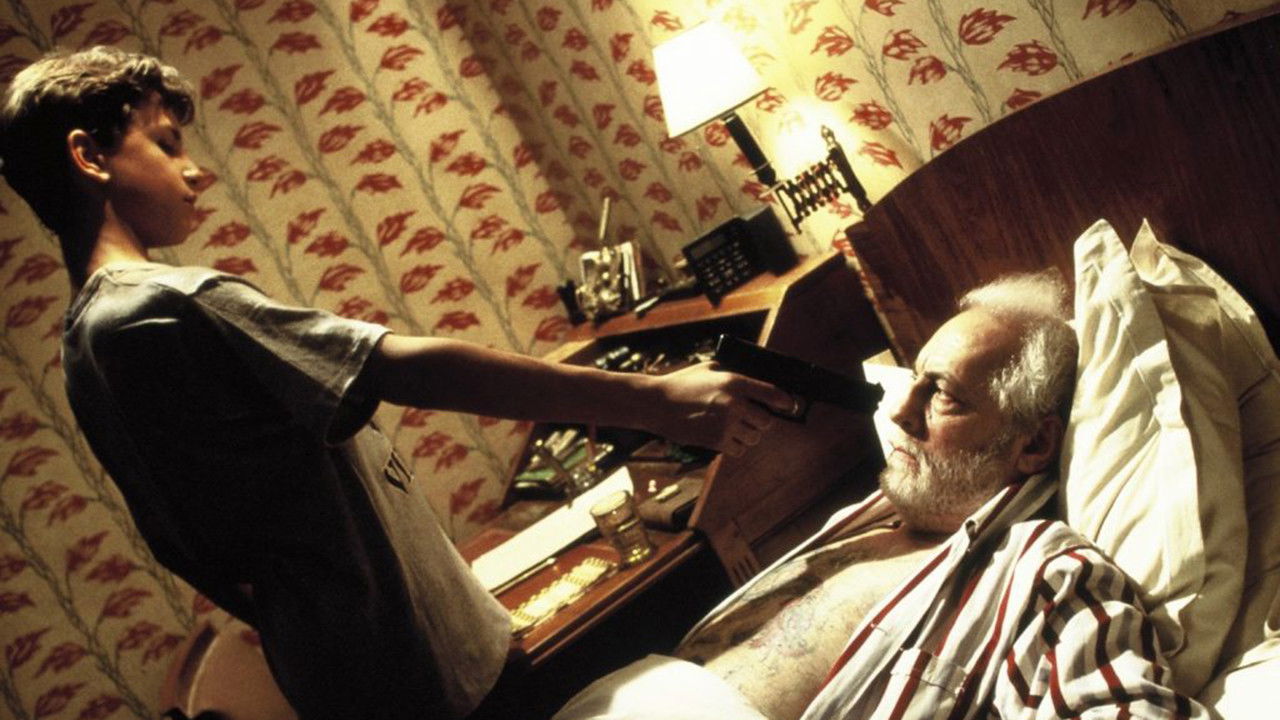

The premise itself is stark: Mr. Wagner, played with haunting weariness by the legendary French actor Michel Serrault, is an aging professional killer. He’s meticulous, lonely, and looking for a way out, or perhaps, a legacy. By chance, he interrupts a burglary attempt by Max (Kassovitz), a disaffected young man adrift in a world saturated by the very violence Wagner perpetrates professionally. Seeing a potential protégé, Wagner takes Max under his wing, initiating him into the grim realities of his trade. The film doesn't flinch from depicting the mechanics of killing, stripping it of glamour and presenting it as a drab, almost bureaucratic process, punctuated by moments of shocking brutality. This procedural coldness is part of what makes Assassin(s) so disturbing; it refuses easy catharsis or stylized action.

Mirrors to a Violent World

What elevates Assassin(s) beyond a simple, grim thriller is its potent, if heavy-handed, critique of societal desensitization. Televisions constantly flicker in the background, blaring news reports of atrocities, mindless game shows, and violent cartoons. This isn't just set dressing; it's the wallpaper of these characters' lives. Max and his even younger, more volatile friend Mehdi (Mehdi Benoufa, in a raw debut performance) seem almost products of this media landscape, their capacity for empathy eroded, their understanding of consequence warped. The film forces us to question the lines between observing violence, consuming it as entertainment, and ultimately, participating in it. Does the relentless media feed numb us, or does it merely reflect a darkness already present? It’s a question that felt relevant in the media-saturated late 90s and perhaps resonates even more uncomfortably today.

Kassovitz: Vision and Burden

Pulling double duty as director and lead actor, Kassovitz crafts a film that is undeniably his vision, yet one senses the shadow of La Haine looming large. Where La Haine crackled with restless energy and righteous anger, Assassin(s) feels deliberately paced, almost suffocatingly controlled. The visual style is muted, often claustrophobic, reflecting the emptiness of the characters' lives. It’s a challenging directorial choice, demanding patience from the viewer. Kassovitz himself delivers a performance of coiled tension as Max, convincingly portraying the journey from petty criminal to apprentice killer, but it's Serrault who anchors the film. Known often for comedic roles earlier in his career (like in La Cage aux Folles), Serrault here is devastatingly effective. His Wagner is a man hollowed out by his profession, his moments of seeming paternal warmth towards Max chillingly juxtaposed with his capacity for detachment. There’s a profound sadness in his eyes, a lifetime of violence weighing him down. It's a masterclass in understated menace and world-weariness.

A Legacy Forged in Discomfort

Let's be clear: Assassin(s) is not an easy film to recommend universally. Its violence is often graphic and disturbing, not for shock value alone, but as an integral part of its thesis. The relentless bleakness and nihilistic undertones can be overwhelming. I remember the tape sitting on my shelf after that first viewing, feeling somehow heavier than others. There was no urge to immediately rewatch it, but its images and questions lingered. The film reportedly faced a difficult production and its poor reception at Cannes impacted its commercial prospects significantly – a stark contrast to the buzz around La Haine. Yet, its willingness to confront uncomfortable truths about violence and its societal reflections is precisely what makes it stick. It’s a prime example of the kind of challenging European cinema that the VHS era made surprisingly accessible – films that didn't coddle the viewer or offer neat resolutions.

Interestingly, the film's script apparently underwent significant changes, with Kassovitz aiming for something even more provocative than his previous work. He wasn't just making a crime film; he was making a statement, however bleak, about the world he saw around him in the mid-90s. Finding specific, concrete "fun facts" about a production this intentionally grim is tough, but the story of its polarising Cannes debut serves as a potent piece of trivia in itself, highlighting its confrontational nature right from the start.

Rating: 6/10

Justifying this score requires acknowledging the film's divisive nature. Assassin(s) is technically proficient, features a powerhouse performance from Michel Serrault, and tackles ambitious, uncomfortable themes with unflinching honesty. Kassovitz directs with a clear, albeit bleak, vision. However, its unrelenting grimness, deliberate pacing, and arguably heavy-handed social commentary can make it an alienating and draining experience. It lacks the kinetic energy of La Haine and its message, while potent, risks feeling nihilistic rather than insightful for some viewers. It earns points for its bravery and Serrault’s unforgettable turn, but loses points for its often punishing tone and lack of narrative nuance beyond its central thesis.

Assassin(s) remains a challenging artifact of 90s French cinema – a cold, hard look at the transmission of violence across generations, wrapped in a critique of media saturation. It’s not a film you "enjoy" in the conventional sense, but one you grapple with, leaving you pondering its bleak questions long after the VCR whirred to a stop.