The cold blue glow of a computer screen in a darkened room. Remember that image? In the mid-90s, it wasn't just a portal to information; it was increasingly becoming a window into obsession, into the darker corners of the human psyche being cataloged and shared. Copycat (1995) taps directly into that burgeoning digital dread, wrapping it around a premise so chillingly plausible it felt less like fiction and more like a grim headline waiting to happen. This wasn't just another serial killer flick; it felt unnervingly researched.

### Trapped by Terror

At the heart of the film is Dr. Helen Hudson, played with brittle brilliance by Sigourney Weaver. We first meet her as a confident expert on serial killers, lecturing with authority. Then, a horrific attack by one of her subjects, the chilling Daryll Lee Cullum (Harry Connick Jr., playing disturbingly against type), leaves her shattered, a prisoner in her own high-tech apartment, crippled by severe agoraphobia. Weaver, known then primarily for the formidable Ellen Ripley in the Alien saga, delivers a performance steeped in palpable vulnerability. You feel the suffocating panic, the walls closing in both physically and mentally. Her research apparently involved deep dives with psychologists and individuals suffering from agoraphobia, and it shows – this isn't a Hollywood caricature of fear, but something raw and exhausting.

The terror escalates when a new killer emerges on the streets of San Francisco, one who meticulously recreates the methods of infamous serial killers from the past – Bundy, Gacy, Dahmer. This isn't random violence; it's a performance, a deadly homage aimed directly at Helen. Tasked with stopping this ghost is Detective M.J. Monahan (Holly Hunter), tough, pragmatic, and initially skeptical of the reclusive academic. Hunter provides the grounded counterpoint to Weaver's frayed nerves, her diminutive stature belying a fierce determination. Their evolving dynamic, moving from distrust to a grudging, necessary reliance, forms the film's emotional core. They are supported by Monahan's partner, Ruben Goetz, played with reliable charm by Dermot Mulroney.

### The Anatomy of Fear

What makes Copycat burrow under your skin isn't just the violence (though the opening attack is brutally effective), but the insidious intelligence behind it. Director Jon Amiel, perhaps better known for dramas like Sommersby (1993), crafts an atmosphere thick with paranoia. The killer isn't just a physical threat; they're a psychological one, exploiting Helen's expertise, turning her life's work into a weapon against her. The screenplay by Ann Biderman and David Madsen was reportedly a hot commodity in Hollywood, and you can see why. It taps into that specific mid-90s fascination with serial killer pathology, spurred by films like The Silence of the Lambs (1991), but gives it a unique, technologically-tinged twist.

Remember how unsettling practical effects could feel back then? While Copycat isn't a gore-fest, its depiction of the crime scenes, echoing infamous real-life killers, carries a disturbing weight. The production design cleverly contrasts Helen's sterile, screen-filled apartment – her cage and her only connection to the outside world – with the grimy reality of the crimes happening just beyond her doorstep. Christopher Young's score deserves mention too, a nervous, often discordant soundscape that amplifies the tension without resorting to cheap stingers. It understands that true dread often lies in anticipation, in the knowledge of what could happen.

One fascinating bit of trivia: the film's budget was a relatively lean $20 million, yet it managed to gross nearly $80 million worldwide. Released the same year as the behemoth Se7en, it perhaps got slightly lost in the shuffle for some, but Copycat holds its own with its focus on the psychological toll and the specific vulnerability of its protagonist. It wasn't just about catching the killer; it was about whether Helen could mentally survive the ordeal. Did that final confrontation genuinely make you hold your breath back then? The way it played on Helen's specific fears felt particularly cruel, and effective.

### Legacy in the Shadows

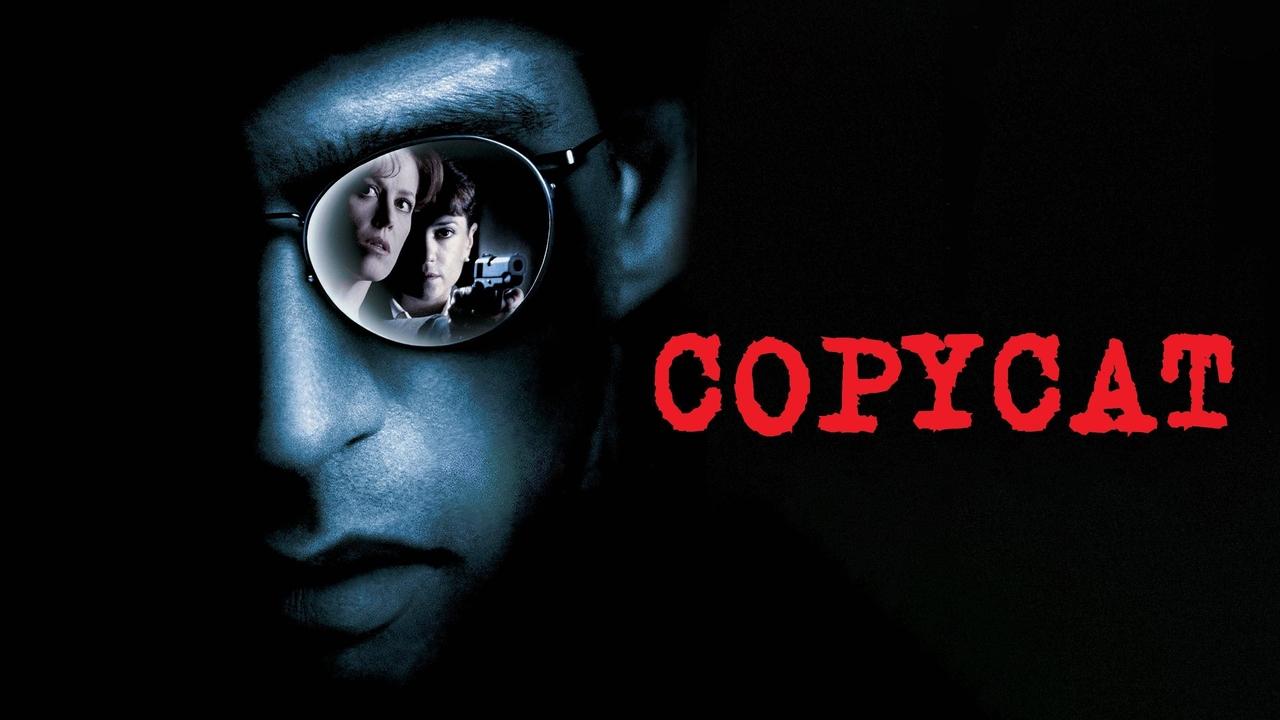

Copycat might occasionally strain credulity with some plot mechanics, as many thrillers do, but its strengths far outweigh its weaknesses. The central performances are commanding, the premise is genuinely chilling, and the execution builds suspense masterfully. It captures that specific 90s blend of burgeoning internet culture, forensic fascination, and deep-seated urban anxiety. I distinctly remember renting this from Blockbuster, the stark cover art promising a sophisticated, scary time, and it delivered. It felt smarter, somehow more insidious than many of its contemporaries.

The film explored themes of trauma, voyeurism, and the dark side of expertise in a way that still resonates. It questioned the very nature of studying monsters – can you truly understand them without becoming tainted yourself? For fans of psychological thrillers from the era, Copycat remains a standout, a tightly wound exercise in suspense anchored by two powerhouse performances.

Rating: 8/10

Justification: Copycat earns its high marks for Sigourney Weaver's and Holly Hunter's compelling performances, a genuinely clever and disturbing premise, Jon Amiel's effective tension-building, and its chilling exploration of psychological vulnerability. While some plot points might require suspension of disbelief, the core concept and atmosphere are potent enough to make it a memorable and effective 90s thriller that tapped into the zeitgeist perfectly.

Final Thought: More than just a procedural, Copycat lingers because it understood that the most terrifying prisons are often the ones we build inside our own minds.