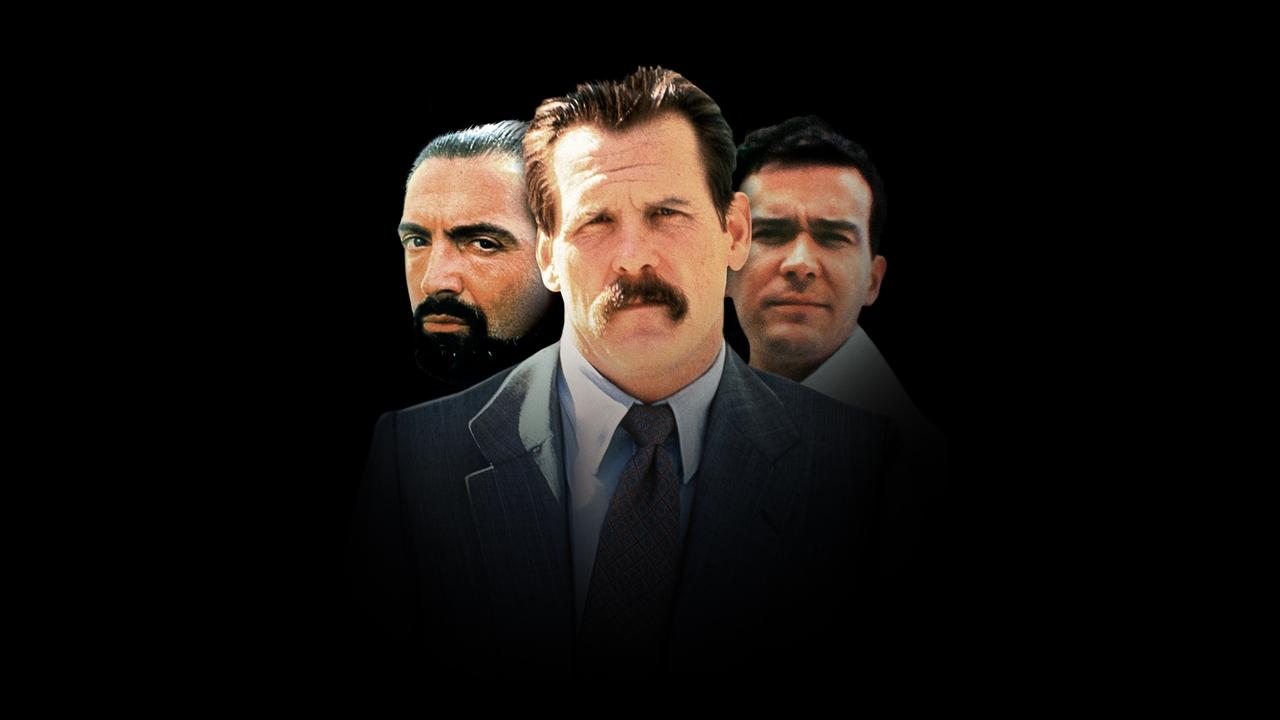

It starts not with a bang, but with a chilling declaration, spat out with casual venom in the dead of night. Nick Nolte, as Lieutenant Mike Brennan, fills the screen – not just physically imposing, but radiating a terrifying certainty in his own poisoned worldview. That opening, a raw nerve exposed, immediately signals that Sidney Lumet's Q & A (1990) isn't here for comfort. It arrived on VHS shelves nestled perhaps between slicker action flicks and broader comedies, but pulling this tape felt different. It promised grit, a descent into the messy, compromised heart of New York City, guided by a director who knew its streets and shadows perhaps better than anyone.

Back on Familiar Ground

Seeing Sidney Lumet’s name on a crime story set in the concrete canyons of New York always felt like a homecoming. The man gave us the righteous fury of Serpico (1973) and the desperate tension of Dog Day Afternoon (1975). With Q & A, adapted from the novel by New York Supreme Court Justice Edwin Torres (who also penned the source material for Carlito's Way), Lumet wasn't just revisiting a genre; he was drilling down into its bedrock corruption. The story kicks off seemingly straightforward: Brennan, a decorated but deeply bigoted detective, executes a small-time hoodlum and claims self-defense. Young, idealistic Assistant District Attorney Al Reilly (Timothy Hutton) is assigned to conduct the perfunctory Q&A session to clear the heroic cop. Simple, right? But the cracks appear almost instantly, revealing a sprawling network of favors, threats, racism, and compromised power stretching from precinct basements to the highest offices.

Nolte Unleashed

Let's be blunt: Nick Nolte's performance as Mike Brennan is monumental. It’s a terrifying force of nature, a portrayal of toxic masculinity and ingrained prejudice so potent it feels dangerous to watch. Nolte reportedly gained weight and fully immersed himself in the role, and it shows. Brennan isn't just a bad cop; he's a walking embodiment of systemic rot, utterly convinced of his own righteousness even as he spews bile and bends the law past its breaking point. He’s charismatic in the most horrifying way, a smiling monster whose casual racism is as shocking today as it was in 1990. There’s no vanity in Nolte’s work here; it's raw, unflinching, and remains one of the most powerful depictions of ingrained bigotry captured on film. It’s the kind of performance that anchors a movie, demanding you grapple with the ugliness it represents.

Navigating the Moral Maze

Opposite Nolte, Timothy Hutton effectively portrays Reilly's dawning horror. He’s our entry point, the initially naive figure whose investigation forces him to confront not only the city’s corruption but also the uncomfortable truths about his own past connections, particularly concerning his former flame, Nancy Bosch (Jenny Lumet, the director's daughter), now involved with the very figures Reilly is investigating. But the film’s other magnetic pole is Armand Assante as Bobby Texador, a suave, intelligent, and dangerous Puerto Rican crime boss. Assante commands the screen, exuding effortless cool and coiled menace. His scenes with both Hutton and Nolte crackle with tension, representing a different kind of power operating within the city's complex ecosystem. Supporting players like Luis Guzmán and Charles S. Dutton also make strong impressions, adding layers to the film's dense tapestry.

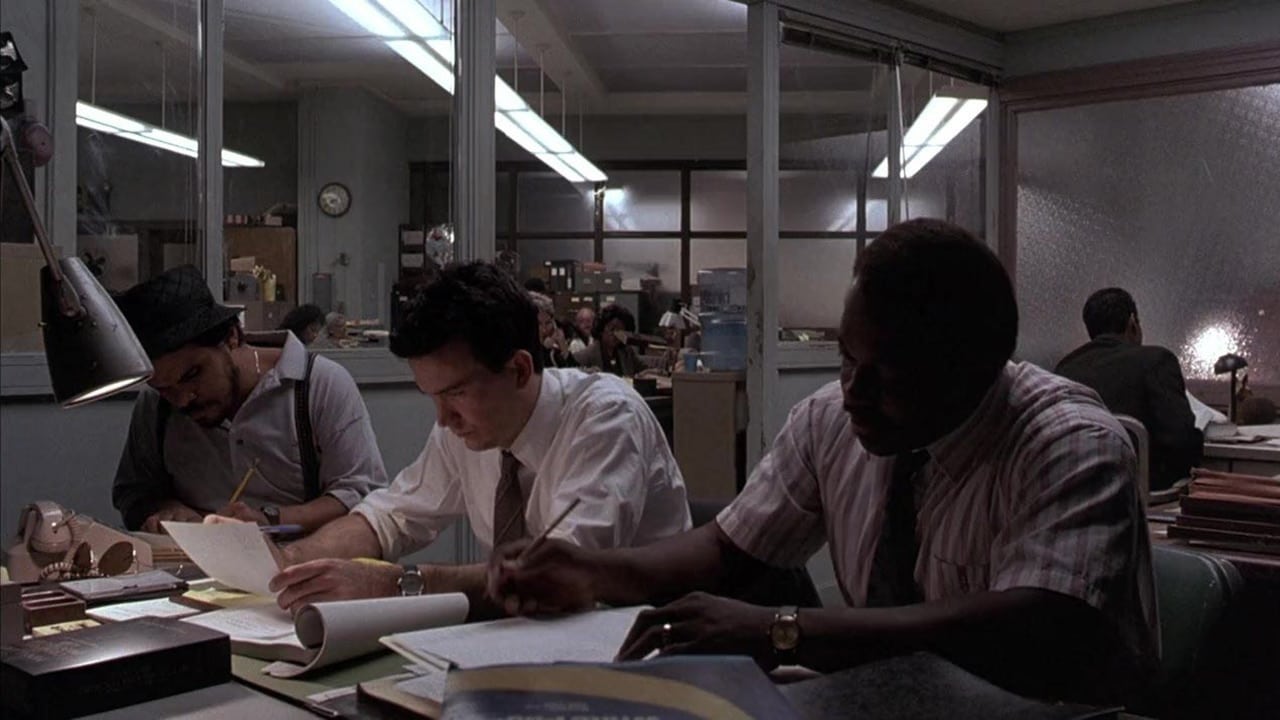

Authenticity in Every Frame

Lumet, ever the master craftsman, shoots Q & A with lean efficiency, letting the dialogue and performances carry the weight. Working again with cinematographer Andrzej Bartkowiak (who also shot Lumet's Prince of the City), he uses over 80 real New York locations, grounding the story in a tangible reality. You feel the grime, the oppressive humidity, the lived-in texture of the city. This isn't a stylized Hollywood version of New York; it's the city Lumet knew intimately. The film’s dialogue, pulled largely from Torres’s authentic voice, is sharp, brutal, and doesn't shy away from the casual racism and homophobia endemic to Brennan's world. It was controversial then, and it remains jarring now, but it feels essential to the film’s uncompromising honesty. Interestingly, despite the critical acclaim for Nolte and the film's power, Q & A wasn't a major box office success, grossing around $11 million on a $10 million budget. Perhaps its darkness was too much for mainstream audiences at the time, cementing its status as a potent, somewhat overlooked gem from the era.

The Questions That Linger

Q & A is not an easy watch. It offers no simple heroes, no comforting resolutions. It forces us to stare into an abyss of corruption where justice is warped, prejudice is wielded as a weapon, and morality is a luxury few can afford. What makes a seemingly good man cross the line? How does systemic rot perpetuate itself? The film doesn’t provide neat answers, but it lays bare the complexities with bracing honesty. Does the casual, accepted bigotry feel disturbingly familiar even decades later? That might be the most unsettling question of all.

Rating: 9/10

This score reflects the film's exceptional strengths: Lumet's taut direction, the powerhouse performances (especially Nolte's unforgettable turn), and its unflinching portrayal of difficult themes. It’s a demanding film, lacking the catharsis of some of Lumet’s earlier work, but its raw power and refusal to compromise make it a standout piece of 90s crime cinema. It earns its high rating through sheer force of conviction and unforgettable character work.

Q & A might not have been the tape you reached for every Friday night back in the day, but finding it felt like uncovering something vital and potent. It’s a reminder that sometimes the most important stories are the ones that refuse to look away.