Ah, the deceptive shimmer of a childhood summer holiday. Remember those endless days under the sun, where the biggest concerns seemed to be sandcastles and ice cream? Yet, sometimes, beneath that golden haze, adult storms were brewing, perceived only in fractured glimpses by younger eyes. That potent blend of sun-drenched nostalgia and simmering domestic tension is precisely the territory mined by Diane Kurys in her deeply personal 1990 film, La Baule-les-Pins (often known by its English title, C'est la Vie). Watching it again, decades later, it feels less like a simple trip down memory lane and more like revisiting a half-remembered photograph, where the smiles hide unspoken complexities.

### That Seaside Feeling

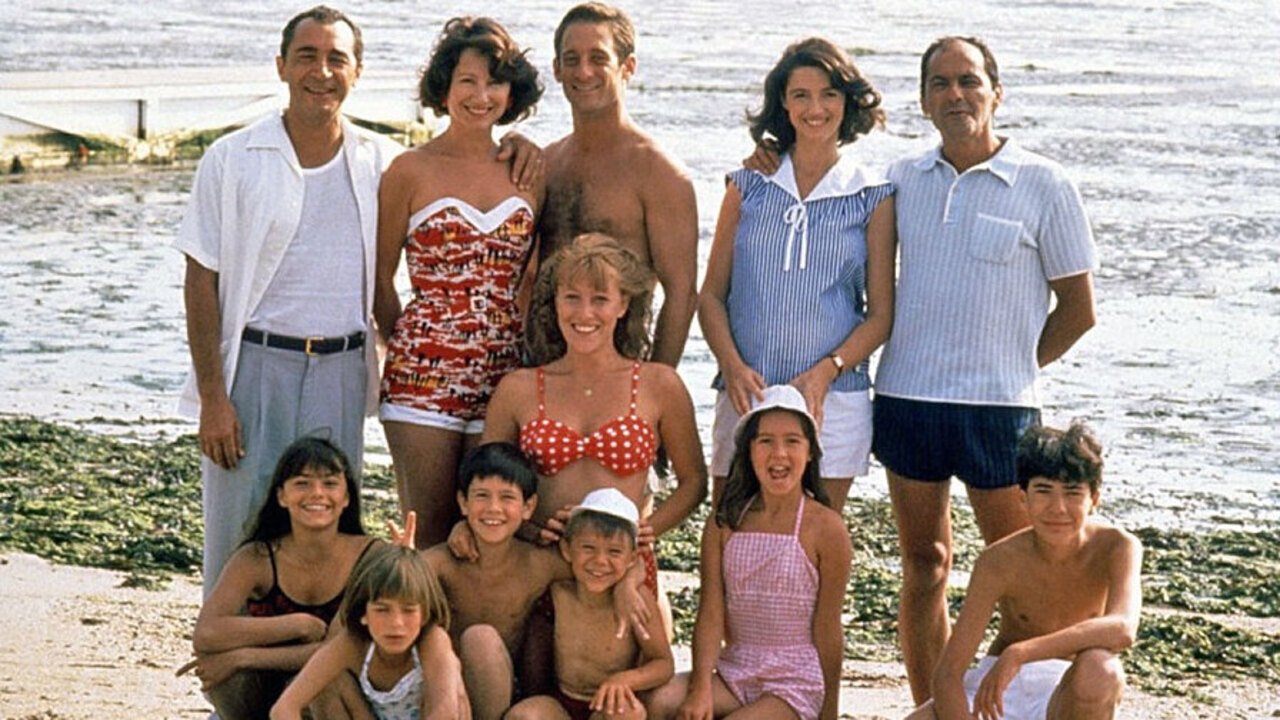

The film plunges us into the summer of 1958, at the French seaside resort of La Baule-les-Pins. Kurys, drawing directly from her own childhood experiences – this film forms a loose trilogy with her earlier works Peppermint Soda (1977) and Cocktail Molotov (1980) – masterfully recreates the specific atmosphere of the era. You can almost smell the salt air mixed with Gauloises smoke, feel the warmth radiating off the pavements, and hear the distant cries of children playing on the vast beach. The setting isn't just backdrop; it's a character in itself, representing a temporary escape, a fragile bubble where family rituals persist even as the foundations crack. We see this world primarily through the eyes of two sisters, 13-year-old Frédérique (Julie Bataille) and 8-year-old Sophie (Candice Lefranc), who arrive for their annual holiday with their aunt Bella (Zabou Breitman) and uncle Léon (Jean-Pierre Bacri) while awaiting their parents.

### Whispers on the Summer Breeze

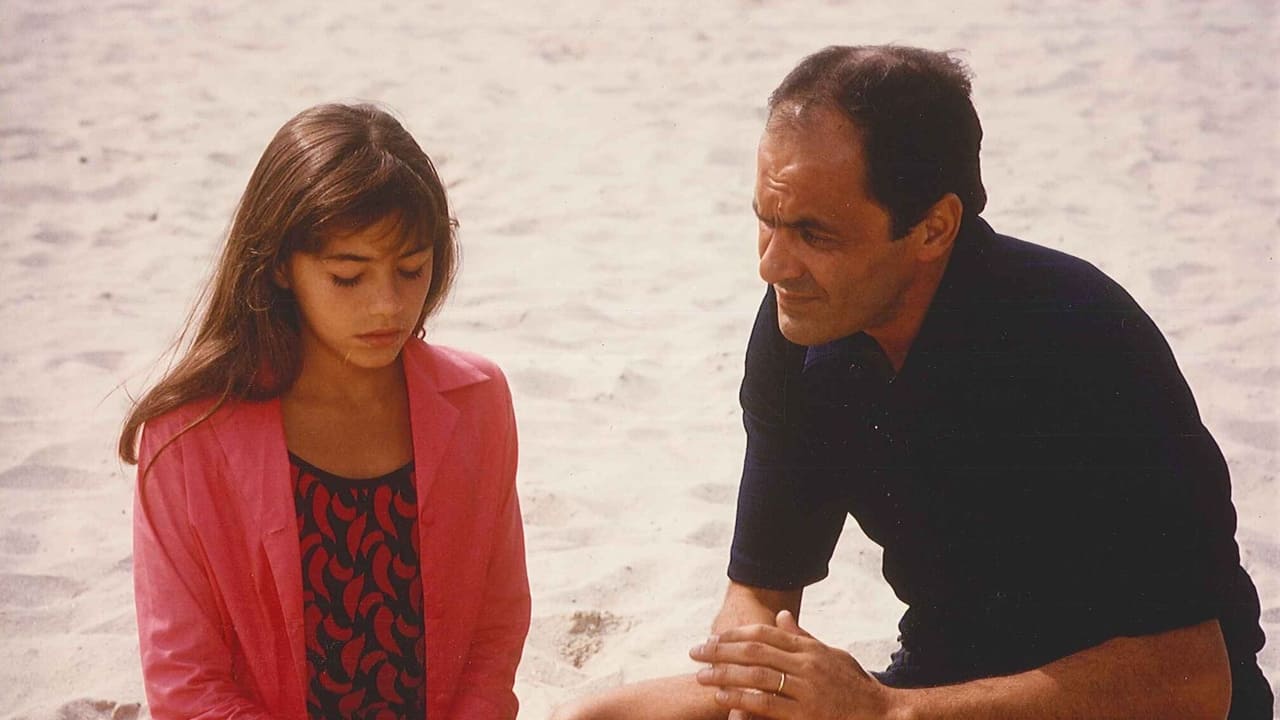

The core of the film lies in the impending separation of the girls' parents, Léna (Nathalie Baye) and Michel (Richard Berry). What makes La Baule-les-Pins so effective, and perhaps quietly devastating, is how Kurys filters this adult drama through the limited, often confused understanding of the children. They catch snippets of hushed arguments, observe loaded glances, and sense the emotional currents shifting around them, piecing together a reality their parents try to shield them from. There are no grand, explanatory confrontations laid bare for the audience; instead, we experience the slow erosion of the marriage much like the girls do – through overheard whispers, unexplained tensions, and the painful awareness that something is irrevocably changing. It forces us to ask, how much do children truly absorb, even when things remain unsaid?

### Performances of Quiet Truth

The acting here is pitch-perfect, grounded in a realism that avoids melodrama. Nathalie Baye, a true luminary of French cinema (think Return of Martin Guerre or even her later turn in Catch Me If You Can), is exceptional as Léna. She conveys a woman caught between societal expectations, maternal love, and a yearning for personal fulfillment (personified by her affair with artist Odette, played by Valeria Bruni Tedeschi). Baye doesn't play Léna as simply neglectful or selfish; she shows us the internal conflict, the moments of warmth juxtaposed with periods of emotional distance dictated by her own turmoil. Richard Berry, as the somewhat detached father Michel, embodies a certain kind of mid-century masculinity – preoccupied with work, perhaps bewildered by his wife's unhappiness, unable to bridge the emotional gap. Their scenes together crackle with unspoken history and resentment.

Equally vital are Zabou Breitman and the ever-reliable Jean-Pierre Bacri as the aunt and uncle. They represent a different kind of domesticity, perhaps more conventional but providing a crucial anchor of relative stability for the girls amidst the parental chaos. Their easy warmth and gentle humour offer moments of respite. And crucially, the young actresses, Julie Bataille and Candice Lefranc, deliver wonderfully naturalistic performances. They aren't precocious movie kids; they feel like real children grappling with emotions they don't fully grasp, their faces registering confusion, resilience, and the dawning awareness of adult fallibility.

### Kurys' Autobiographical Eye

Diane Kurys directs with a sensitive, observational style. Having lived through the events that inspired the film (the separation of her own parents one summer in La Baule), she brings an authenticity that’s palpable. The camera often lingers, capturing small gestures and fleeting expressions that speak volumes. The pacing is unhurried, mirroring the languid rhythm of summer itself, allowing the emotional weight to accumulate gradually. A fascinating tidbit: filming on location in the actual La Baule-les-Pins undoubtedly added another layer of verisimilitude, connecting the production directly to the director’s formative memories. It wasn't just about recreating the 1950s; it was about recapturing a specific feeling tied to a specific place. The film was well-received in France, appreciated for its nuanced portrayal of family dynamics and its delicate handling of difficult subject matter from a child's perspective.

### The Lingering Taste of Salt and Sadness

La Baule-les-Pins isn't a film packed with dramatic plot twists or explosive confrontations. Its power lies in its quiet acuity, its understanding of how seismic shifts in family life are often experienced not as a sudden earthquake, but as a series of tremors felt beneath the surface of everyday life. It captures that bittersweet pang of nostalgia for childhood summers while simultaneously acknowledging the hidden pains that often accompany those memories. It reminds us that the postcard-perfect moments are rarely the whole story. What stays with you is the pervasive sense of melancholy hanging in the sunlit air, the feeling of an ending disguised as a holiday.

Rating: 8.5/10

Justification: The film earns this high rating for its exceptional performances (especially Baye and the children), Kurys' deeply personal and sensitive direction, its evocative atmosphere, and its poignant, truthful exploration of childhood perspective amidst family breakdown. It masterfully balances nostalgia with emotional honesty. While its deliberately measured pace might not suit everyone, its quiet power is undeniable.

Final Thought: La Baule-les-Pins is a beautifully rendered memory piece, a reminder that even the brightest summers can cast long shadows, and that the end of innocence often arrives not with a bang, but with a whispered revelation on a seaside breeze. A must-watch for fans of nuanced European cinema and reflective coming-of-age stories.