There’s a particular kind of heat haze that settles over certain adolescent summers, a shimmering mix of boredom, restless energy, and an almost painful yearning for transformation. It’s a feeling Claude Miller’s 1985 film An Impudent Girl (originally L'Effrontée) captures with such aching precision, it feels less like watching a movie and more like retrieving a half-forgotten memory. Seeing it again, perhaps on a worn VHS copy pulled from the back of the shelf like mine was for years, transports you right back to that cusp of change, where everything feels simultaneously mundane and electrically charged with possibility.

That Summer Feeling

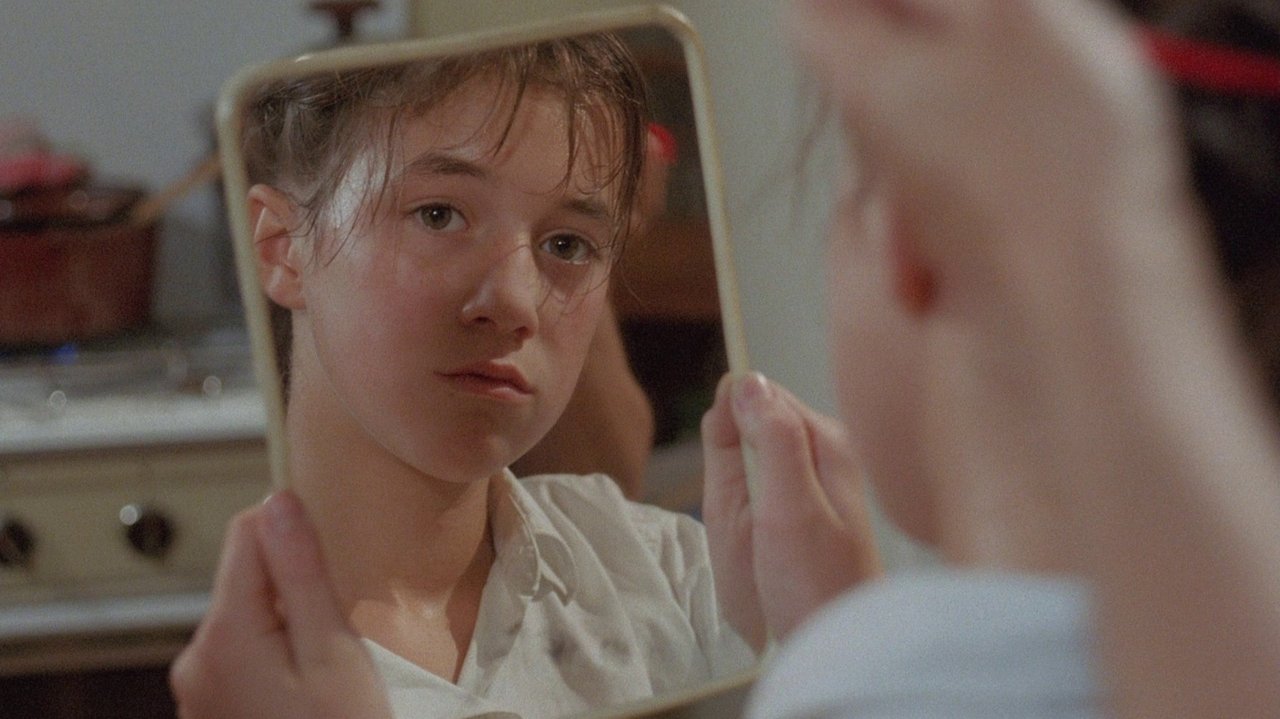

Set in a sleepy French provincial town during a long, hot summer, the film orbits around 13-year-old Charlotte (Charlotte Gainsbourg in a truly stunning debut). She lives a rather unremarkable life with her distracted father and older brother, finding companionship mainly with the younger, sickly Lulu (Julie Glenn) and navigating the weary wisdom of their housekeeper, Léone (Bernadette Lafont). Charlotte is prickly, awkward, often sullen – the titular "impudent girl" – but beneath the adolescent armor simmers a desperate desire to escape her perceived mediocrity. She dreams of something bigger, brighter, more sophisticated than the dusty streets and familiar faces of her hometown.

A Glimpse of Another World

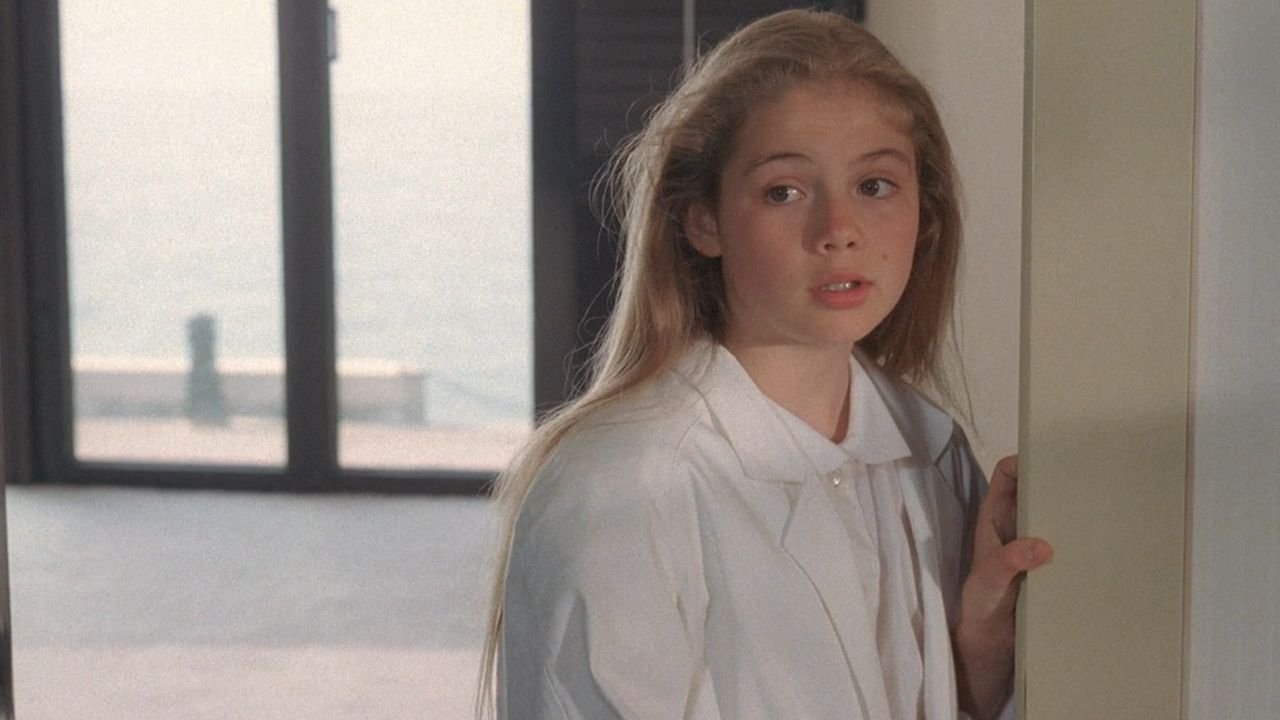

The catalyst for Charlotte's simmering discontent arrives in the form of Clara Baumann (Clothilde Baudon), a slightly older, exceptionally talented young concert pianist who is temporarily staying nearby. Clara represents everything Charlotte is not: poised, wealthy, accomplished, seemingly gliding through a world of culture and privilege. Meeting Clara ignites Charlotte's imagination, offering what feels like a tangible escape route. She becomes instantly infatuated, not necessarily romantically, but with the idea of Clara and the life she represents. This encounter throws the stark realities of class difference and the often-illusory nature of adolescent dreams into sharp relief. Doesn't that sudden glimpse of perceived perfection often make our own world feel unbearably small when we're young?

A Star is Born

At the absolute heart of An Impudent Girl is Charlotte Gainsbourg. It’s almost impossible to overstate how remarkable her performance is, especially considering it was her first film role at just 14. She embodies Charlotte with a raw, unvarnished naturalism that feels utterly authentic. Every awkward gesture, every defiant glare, every flicker of vulnerability across her face rings true. There's no trace of polished precociousness; instead, we see the messy reality of a girl grappling with complex emotions she barely understands. It's a performance of quiet intensity, revealing the turbulent inner world beneath the often-bratty exterior. Interestingly, Gainsbourg, daughter of the iconic Serge Gainsbourg and Jane Birkin, stepped into the spotlight with a talent entirely her own, instantly proving she was far more than just her famous lineage. Her performance deservedly earned her the César Award for Most Promising Actress, a sign of the incredible career to come.

The supporting cast orbits Gainsbourg perfectly. Bernadette Lafont, a legend of the French New Wave, brings a grounded warmth and weary exasperation to Léone, the housekeeper who sees Charlotte more clearly than perhaps anyone else. Jean-Claude Brialy, another stalwart of French cinema, adds a layer of ambiguous charm as Sam, the musician linked to Clara’s world, whose attention Charlotte briefly courts.

Miller's Observational Grace

Director Claude Miller, known for films like the intense thriller Garde à Vue (1981), demonstrates a wonderfully sensitive touch here. He observes Charlotte’s world with patience and empathy, letting the story unfold through small moments and nuanced interactions rather than big dramatic pronouncements. The pacing is deliberate, mirroring the languid pace of that endless summer. Miller, along with co-writers Luc Béraud, Bernard Stora, and Annie Miller, adapted the screenplay from Carson McCullers' novel "The Member of the Wedding," and they retain that book’s keen psychological insight into the adolescent psyche. The direction feels intimate, allowing us to inhabit Charlotte's perspective, sharing her frustrations and fleeting joys. The film doesn't judge Charlotte for her 'impudence'; it understands the root of her unhappiness.

A Quietly Resonant Gem

Finding An Impudent Girl back in the day, perhaps tucked away in the 'World Cinema' section of the video store, felt like discovering something special. It wasn't a flashy blockbuster, but a quiet, character-driven piece that resonated deeply. Unlike some of the more heightened American teen dramas of the 80s, it approached adolescence with a distinctly European sensibility – melancholic, introspective, and unflinchingly honest about the pains of growing up. The film didn't shy away from the character's unlikeable moments, making her journey feel all the more real. It also picked up the prestigious Louis Delluc Prize in France, cementing its critical acclaim. Does the film still hold up? Absolutely. Its themes of yearning, disillusionment, and the bittersweet process of self-discovery are timeless.

What lingers most after the credits roll is that poignant understanding of youthful desire – the desperate need to be someone else, somewhere else, which often blinds us to the value of our own lives and the people already in them. It’s a film that captures the specific pang of realizing that the escape you craved might not be the answer, and that growing up involves finding your place within the world you already inhabit, however imperfect.

Rating: 9/10

This rating reflects the film's exceptional central performance, its sensitive direction, its evocative atmosphere, and its timeless portrayal of adolescent angst and yearning. It’s a near-perfect capture of a specific emotional landscape. An Impudent Girl remains a profoundly moving and insightful coming-of-age classic, a quiet gem from the VHS era that reminds us of the intense, confusing, and ultimately formative power of those transitional summers. It leaves you contemplating the subtle shifts that mark the end of childhood, long after the tape has rewound.