### Unraveling Desire's Logic

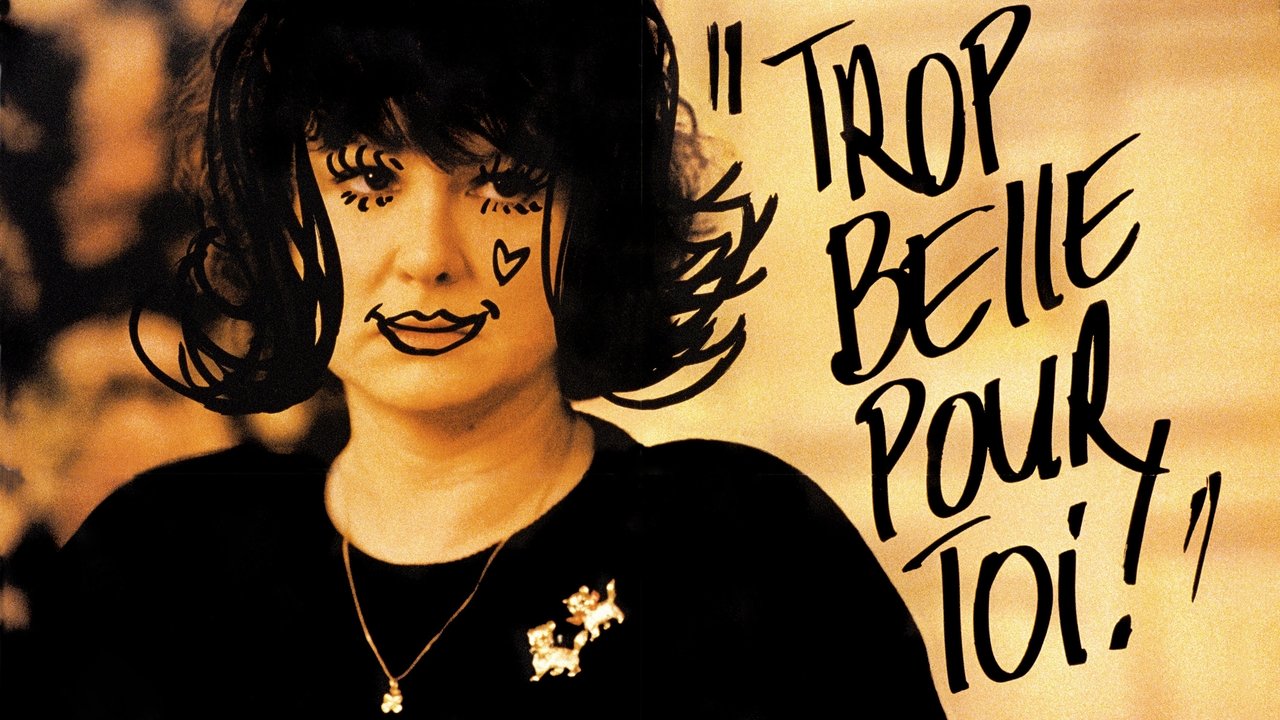

What makes the heart choose what it chooses? It’s a question that cinema, in its myriad forms, constantly circles. Yet, few films tackle it with the unnerving, sometimes abrasive honesty of Bertrand Blier’s 1989 drama Too Beautiful for You (original title: Trop belle pour toi). Forget the neat Hollywood triangles; Blier throws convention out the window, presenting a scenario that feels both absurd and painfully recognizable: a successful garage owner, Bernard (Gérard Depardieu), married to the stunningly elegant Florence (Carole Bouquet), finds himself irresistibly drawn to his temporary secretary, Colette (Josiane Balasko), a woman often described, even within the film's world, as plain. This isn't a simple affair; it's an exploration of attraction that bypasses societal scorecards entirely.

### Beyond the Surface

The film’s power lies in its refusal to offer easy answers or judge its characters. Blier, who also penned the screenplay, isn't interested in painting Bernard as a villain or Colette as merely a homewrecker. Instead, he delves into the complex currents beneath the surface. Florence, played with an almost ethereal grace by Carole Bouquet (a former Bond girl from For Your Eyes Only), represents a certain kind of idealized, almost untouchable beauty. She is sophisticated, intelligent, wealthy – the perfect partner on paper. Yet, perhaps that perfection creates a distance, an environment where genuine, messy connection struggles to take root. I recall watching this on a slightly worn VHS copy years ago, the subtitles occasionally flickering on the CRT screen, and being struck by how uncomfortable the film deliberately makes you feel, forcing you to confront your own assumptions about beauty and desire.

It’s the performance of Josiane Balasko as Colette that anchors the film’s challenging premise. Balasko, often known for broader comedic roles (and a frequent collaborator with the Splendid troupe, including films like Santa Claus is a Stinker), brings a profound depth and vulnerability to Colette. She isn't conventionally beautiful, and the film doesn't pretend otherwise. But she possesses a grounded warmth, an unassuming intelligence, and a directness that pierces through Bernard's carefully constructed life. Balasko portrays Colette not as a victim or a temptress, but as a woman surprised and perhaps overwhelmed by an attraction that defies logic. Her chemistry with Gérard Depardieu, reprising a very different dynamic from their earlier, wilder pairing in Blier's own Les Valseuses (1974), feels startlingly authentic. You believe their connection, even if you can't entirely explain it through conventional romantic tropes. Depardieu, at the height of his international fame following Jean de Florette, masterfully conveys Bernard’s confusion, passion, and the gnawing realization that his life is unraveling in ways he never anticipated.

### Blier's Bold Strokes

Bertrand Blier's direction is as unconventional as his narrative. He employs jarring cuts, moments of surreal fantasy, and characters occasionally breaking the fourth wall or speaking their inner thoughts aloud. Most notably, he weaves Franz Schubert's music throughout the film, not merely as background score, but as an active participant, its romantic swells often contrasting sharply with the raw, unvarnished emotions on screen. This deliberate dissonance prevents the film from ever becoming a comfortable melodrama. It keeps the viewer slightly off-balance, mirroring the characters' own internal turmoil.

It's a film that provoked considerable discussion upon release, even winning the prestigious Grand Prix at the 1989 Cannes Film Festival. It wasn't just the central premise; it was Blier's willingness to present complex, flawed adults navigating the bewildering landscape of mid-life desire without easy moral signposts. This wasn't the kind of film you casually rented for a light evening; it was the sort of challenging European cinema that sometimes surfaced in the 'World Cinema' section of the video store, promising something deeper, perhaps more unsettling, than the usual Hollywood fare. Finding it felt like a small victory, a portal into a different kind of storytelling.

### The Unexpected Pull

What lingers long after the tape clicks off is the film's central question about attraction. Is it merely shared interests, physical appearance, societal approval? Or is it something more primal, inexplicable – a recognition, perhaps, of a shared vulnerability or an unspoken need? Too Beautiful for You suggests the latter. Bernard isn't leaving perfection for imperfection; he's drawn to a different kind of completeness, a connection that feels more tangible, more real, than the perhaps too-perfect life he shares with Florence. The film doesn't necessarily endorse his actions, but it demands empathy for the powerful, often illogical forces that drive human behavior.

It explores the idea that sometimes, what we think we should want isn't what truly satisfies the soul. Colette offers Bernard something Florence, despite her beauty and sophistication, cannot – perhaps an escape from expectation, a space where he can be less than perfect himself. Doesn't this resonate with the complexities we see in relationships around us, even today?

Rating: 8/10

Too Beautiful for You is a challenging, insightful, and superbly acted piece of late 80s French cinema. Its unconventional style and refusal to offer easy judgments make it a demanding watch, but the powerhouse performances from Depardieu, Balasko, and Bouquet, coupled with Blier's audacious direction, create a compelling and unforgettable exploration of desire's perplexing nature. It earns its 8 not for being conventionally entertaining, but for its artistic bravery, its emotional honesty, and the lingering questions it poses about why we love who we love. It remains a potent reminder that sometimes, the most profound connections are found where we least expect them, far from the polished surfaces of conventional beauty.