It arrives not with a bang, but with the quiet hum of a video camera. sex, lies, and videotape landed in 1989, a year often remembered for bombastic blockbusters, yet this unassuming film felt like a whispered secret suddenly spoken aloud. Its title promised salaciousness, the kind splashed across lurid paperback covers or hinted at in late-night cable slots. What audiences discovered instead was something far more unsettling and resonant: a starkly intimate portrait of emotional disconnection, viewed through the unblinking eye of a lens. It wasn't just a movie; it felt like eavesdropping on the anxieties of an era shifting under our feet.

An Uncomfortable Intimacy

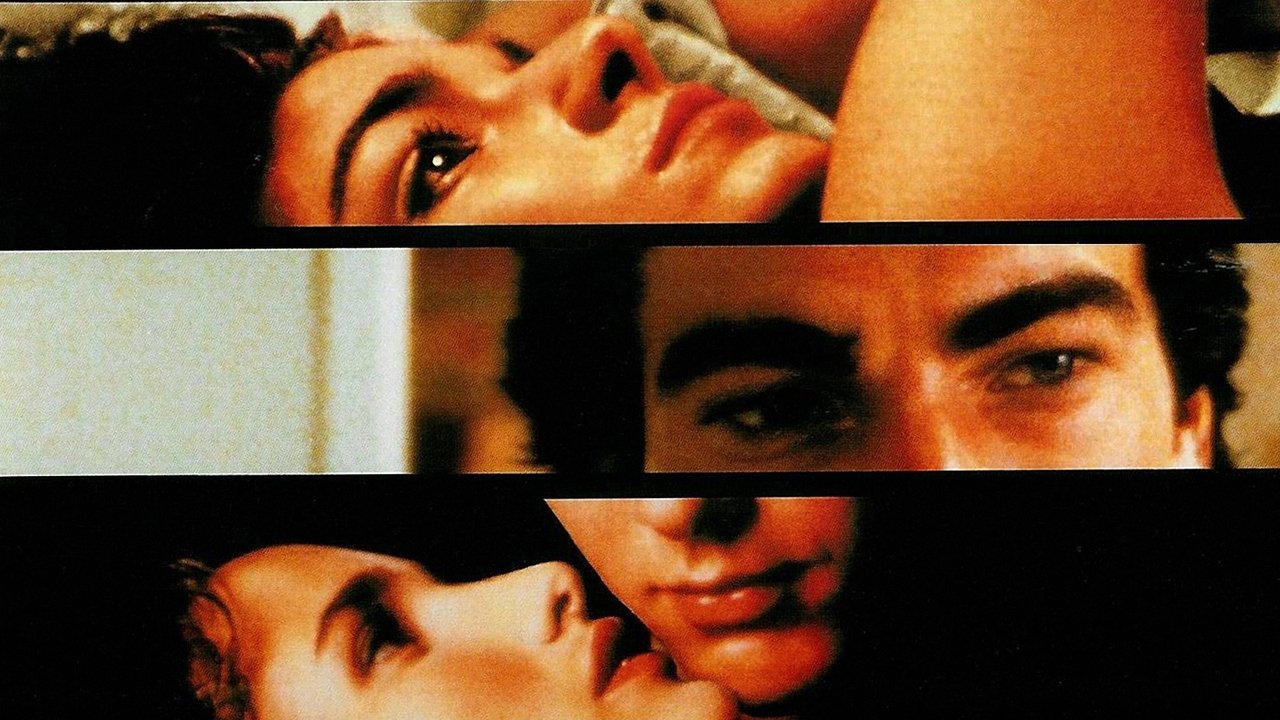

Set against the humid backdrop of Baton Rouge, Louisiana – director Steven Soderbergh's own hometown – the story revolves around a tangled quartet. Ann Bishop Mullany (Andie MacDowell) is trapped in a sterile marriage to her philandering husband, John (Peter Gallagher), a successful but deeply insecure lawyer. John is carrying on a brazen affair with Ann's own sister, the fiery and uninhibited Cynthia (Laura San Giacomo). Into this simmering pot of repressed desires and deceit walks Graham Dalton (James Spader), an old college friend of John's who drifts back into town. Graham carries his own baggage, quite literally, in the form of a camcorder and a collection of tapes containing interviews with women discussing their sexual experiences. He claims impotence, finding his only release through watching these recorded confessions.

The premise sounds almost like a high-concept gimmick, but Soderbergh, who famously penned the sharp, observant script in just eight days during a road trip back from a failed relationship, uses it as a scalpel. The videotapes become less about titillation and more about truth – or at least, the performance of it. In a world where characters lie easily to each other and perhaps even more readily to themselves, the camera offers a strange, mediated form of honesty. It becomes a confessional, a therapist's couch, and a catalyst for change, forcing each character to confront the messy reality beneath their carefully constructed surfaces.

Performances That Resonate

What elevates sex, lies, and videotape beyond its intriguing concept are the pitch-perfect performances. James Spader, already known for playing charismatic creeps (Pretty in Pink, Less Than Zero), delivers a career-defining turn as Graham. He imbues the character with an unsettling stillness, a quiet intensity that is both unnerving and strangely magnetic. There's a vulnerability beneath the voyeurism, a palpable sense of damage that makes his peculiar compulsion feel less like a perversion and more like a coping mechanism. It's a performance built on nuance – the slight shifts in expression, the measured cadence of his speech – that stays with you long after the credits roll.

Andie MacDowell, in a role Soderbergh reportedly fought hard for the studio to accept, is equally compelling as Ann. She beautifully captures the slow thaw of a woman suffocating under the weight of propriety and marital disillusionment. Her initial interactions with Graham are hesitant, wary, but as she opens up, first to her therapist and then, crucially, to Graham's camera, we witness a quiet blossoming of self-awareness. It’s a subtle, deeply internal performance that anchors the film's emotional core. Peter Gallagher expertly embodies the casual arrogance and underlying desperation of John, while Laura San Giacomo, in a star-making performance, injects the film with raw, unapologetic energy as Cynthia, the character perhaps most honest about her desires, even if her actions are entangled in the web of deceit.

The Indie Revolution Begins

It’s impossible to discuss sex, lies, and videotape without acknowledging its monumental impact. Made for a shoestring budget of around $1.2 million (roughly $2.9 million today), it became a sensation. After winning the Audience Award at the 1989 Sundance Film Festival, it went on to stun the international film community by winning the prestigious Palme d'Or at the Cannes Film Festival – an almost unheard-of achievement for a 26-year-old first-time director. This critical adoration translated into box office gold, earning nearly $25 million domestically (around $60 million today) and essentially launching Miramax Films as a major force in independent cinema. It proved that small, character-driven stories focused on dialogue and psychological depth could find a significant audience, paving the way for the indie boom of the 1990s.

Watching it today, perhaps on a worn VHS copy pulled from the back shelf, the film retains its power. The technology feels quaint – the bulky camcorder, the analog tapes – but the themes are timeless. The search for authentic connection, the ways we use technology to both bridge and create distance, the complexities of intimacy and honesty... these are anxieties that resonate just as strongly now, perhaps even more so. Soderbergh's direction is confident and restrained, focusing entirely on character and atmosphere, letting the silences speak as loudly as the dialogue. There are no flashy stylistic flourishes, just clean, observant filmmaking that serves the story.

The Verdict

sex, lies, and videotape isn't a film you watch for spectacle; it's one you experience. It draws you into its hermetically sealed world of quiet desperation and unexpected connection. The performances are captivating, the script is razor-sharp, and its influence on the landscape of American film is undeniable. It's a reminder that sometimes the most profound stories are the ones whispered in confidence, even if that confidence is mediated through the cold lens of a camera. It doesn't just hold up; it feels eerily prescient.

Rating: 9/10

It remains a landmark achievement, a quiet earthquake that reshaped independent film. Decades later, the questions it poses about truth, intimacy, and how we see ourselves still linger, much like the faint static of an old VHS tape paused on a revealing frame.