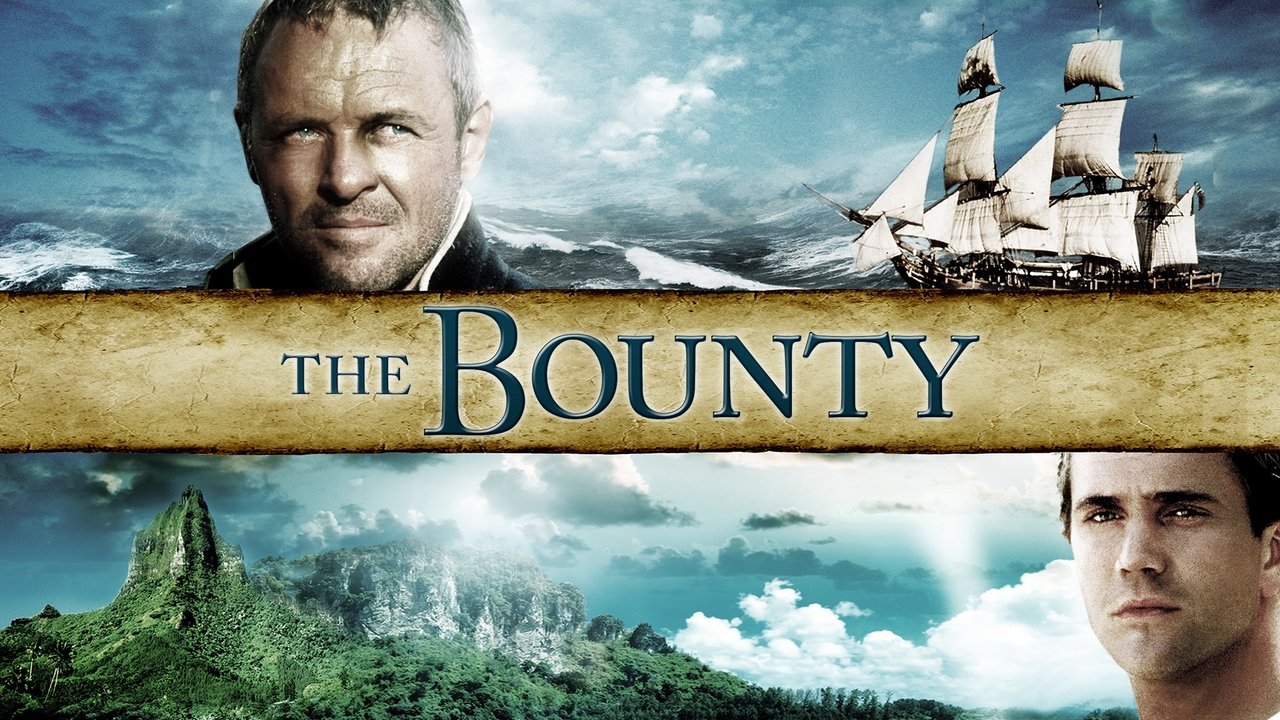

It’s a story etched into maritime lore, a potent cocktail of adventure, tyranny, and rebellion under the vast Pacific sky. The Mutiny on the Bounty. We’ve seen it unfold before on screen, famously with Laughton and Gable in 1935, then Brando and Howard in 1962. But when the 1984 version, simply titled The Bounty, sailed into view, it offered something different. Helmed by New Zealand director Roger Donaldson (who would later give us tense thrillers like No Way Out (1987) and Thirteen Days (2000)), this retelling felt less like a clear-cut tale of villainy and heroism, and more like a complex, psychologically fraught examination of men pushed to their absolute limits. It aimed for a historical grit that felt distinctly, well, 80s in its execution, yet timeless in its themes.

A Shadow of What Might Have Been

There's a fascinating "what if?" hanging over this production. Originally, this was envisioned as a two-part epic directed by the legendary David Lean, penned by his frequent collaborator Robert Bolt (the genius behind Lawrence of Arabia (1962) and Doctor Zhivago (1965)). Lean’s version ultimately collapsed under financial woes, a tantalizing ghost in cinematic history. But Bolt’s script, adapted from Richard Hough’s more nuanced historical account Captain Bligh and Mr. Christian, survived. What emerged, under Donaldson’s capable direction, retains Bolt’s focus on the psychological friction and historical ambiguity, even if it lacks Lean's potential grandiosity. It sought to present a Captain Bligh less as a monster and more as a man cracking under immense pressure, and a Fletcher Christian driven by more than simple idealism. This commitment to a murkier truth is perhaps the film's greatest strength. I recall renting this tape, perhaps initially drawn by the familiar story or the promise of high-seas drama, but finding myself gripped by its darker, more questioning tone.

Pressure Cooker at Sea

Donaldson excels at capturing the stifling reality of life aboard the HMS Bounty. You feel the cramped quarters, the oppressive humidity, the rigid hierarchy grating against the sailors' frayed nerves during the arduous voyage to Tahiti. The mission itself – collecting breadfruit plants to transplant as cheap food for slaves in the West Indies – carries a grim undertone of colonial enterprise. When they finally reach Tahiti, the contrast is stark: lush, sensual, liberating. The extended stay, necessary for the breadfruit to mature, becomes a catalyst. The crew tastes freedom, forms bonds, and the eventual order to return to the brutal discipline of the sea feels like a sentence. Arthur Ibbetson’s cinematography captures both the claustrophobia of the ship and the intoxicating beauty of Polynesia, making the crew’s (and Christian’s) temptation entirely understandable. Doesn’t that sudden shift from paradise back to harsh reality feel like a universal human experience, writ large upon the ocean?

Hopkins and Gibson: A Duel of Wills

At the heart of the film lies the simmering conflict between Lieutenant William Bligh and Fletcher Christian, brought to life by two actors hitting formidable strides. Anthony Hopkins, years before Hannibal Lecter but already radiating coiled intensity, gives us a Bligh who is ambitious, insecure, and tragically bound by the unforgiving naval code of the era. He’s capable of kindness but prone to volcanic bursts of temper and cruel, status-driven punishments. Hopkins doesn't ask us to like Bligh, but he compels us to understand the immense strain he’s under, navigating not just the ship but the complex social strata aboard. His Bligh is flawed, perhaps even incompetent in his man-management, but undeniably human.

Opposite him, Mel Gibson, fresh off the raw energy of the Mad Max films and Gallipoli (1981), embodies Fletcher Christian. He’s initially Bligh’s friend and protégé, torn between his duty and his growing empathy for the crew, as well as his own enchantment with Tahiti and his relationship with Mauatua (Tevaite Vernette). Gibson portrays Christian’s transformation from loyal officer to reluctant mutineer with a brooding charisma. You see the internal struggle, the weight of the decision. Their scenes together crackle with tension – the polite formalities barely masking the resentment and eventual hatred. It’s a clash less of archetypes and more of two specific, tragically incompatible personalities caught in an impossible situation.

Echoes of Talent, Sounds of the Era

The supporting cast is remarkable, adding layers of authenticity. Look closely and you’ll spot future titans Daniel Day-Lewis as the conflicted, passed-over Sailing Master John Fryer and Liam Neeson as the hulking, mutinous Charles Churchill. Even the legendary Laurence Olivier lends immense gravity to his brief scenes as Admiral Hood during the opening court-martial. Their presence elevates the entire production. And then there’s the score by Vangelis, famous for Chariots of Fire (1981) and Blade Runner (1982). Its synthesizers are undeniably of their time, yet manage to evoke both the vastness of the ocean and the rising emotional tide aboard the ship. It might feel dated to some ears now, but back then, watching on a CRT with the volume up, it felt epic and strangely haunting.

Production wasn't easy. A replica ship, The Earl of Pembroke, was sailed thousands of miles to the filming locations in Moorea, Tahiti, and New Zealand. The logistics were challenging, mirroring, in a small way, the difficulties of the original voyage. Despite its pedigree, strong performances, and production value (costing around $20-25 million), the film wasn't a huge box office success (around $8.6 million domestic). Perhaps its moral ambiguity and downbeat ending didn't align with the more gung-ho blockbusters of the mid-80s?

The Lingering Wake

The Bounty doesn’t offer easy answers about who was right or wrong. It presents a tragedy born of rigid structures, human fallibility, and the seductive, disruptive power of a different way of life. It asks us to consider the pressures of command, the breaking point of loyalty, and the complex legacy of exploration and colonialism. What stays with you isn't just the dramatic mutiny itself, but the faces of the men – Hopkins' strained rigidity, Gibson's troubled conscience, the desperation and fleeting joys of the crew. It feels less like a swashbuckling adventure and more like a historical drama with a deep psychological core.

Rating: 8/10

This score reflects the film's powerful lead performances, its commitment to a more complex historical interpretation than its predecessors, its strong sense of atmosphere, and its impressive production values. While the Vangelis score might polarize modern viewers and some might find the pacing deliberate, the central conflict and Donaldson's steady direction make it a compelling and thoughtful piece of 80s cinema. It stands as a potent reminder that sometimes the most dramatic voyages are the ones that navigate the treacherous waters of the human heart. It's a version of the Bounty story that truly lingers, prompting questions long after the haunting synths fade out.