It arrives not with a bang, nor a whimper, but with a rhythm. A human pulse, captured on film and amplified by sound, emanating from corners of the world often relegated to the background hum of the evening news. Powaqqatsi (1988), the second installment in director Godfrey Reggio’s ambitious Qatsi trilogy, isn't a film you simply watch; it’s an experience you absorb, a dense tapestry of sight and sound that washes over you, leaving contemplation in its wake. Finding this on the shelf back in the day, nestled perhaps between a Schwarzenegger action flick and a John Hughes comedy, must have felt like discovering a transmission from another dimension entirely.

### The Human Current

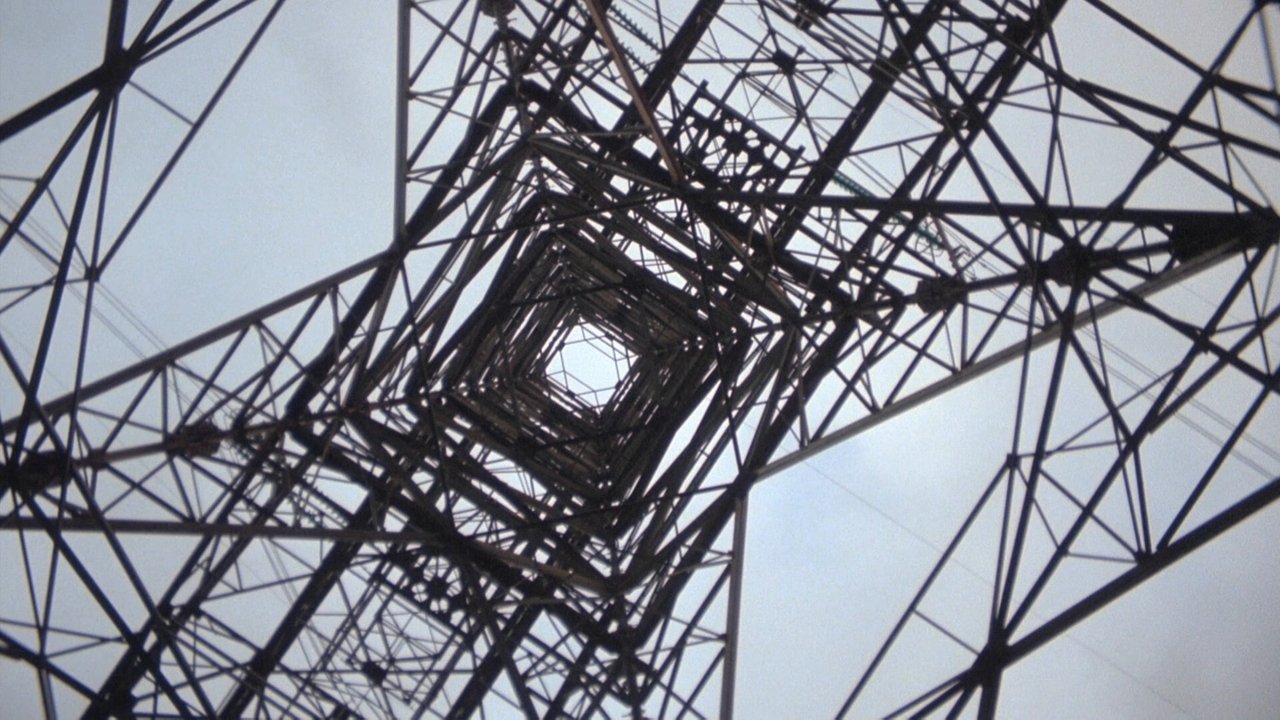

Where its predecessor, Koyaanisqatsi (1982), often focused on the dizzying, impersonal scale of modern infrastructure and technology consuming nature, Powaqqatsi turns its gaze directly toward humanity, specifically the people of the Global South – Asia, Africa, South America. The title itself, derived from the Hopi language, translates roughly to "parasitic way of life" or, perhaps more fittingly here, "life in transition." This transition is the film's central preoccupation. Reggio, aided by cinematographers Graham Berry and Leonidas Zourdoumis, employs hypnotic slow-motion and keenly observed framing to elevate everyday labor into something profound, almost ritualistic. We see miners emerging from the earth, fishermen casting nets, women carrying burdens, children playing amidst ancient structures – each frame pulses with life, dignity, and often, immense physical effort. There's an undeniable beauty here, a celebration of resilience and community, but it's tinged with an underlying melancholy.

### Progress and Its Shadow

The film doesn't offer easy answers or explicit narration. Instead, it juxtaposes images of traditional life – rich in colour, community, and spiritual expression – with the encroaching, often overwhelming, presence of industrialization and Western influence. A hand-pushed cart labours alongside a sputtering truck; ancient marketplaces give way to congested city streets; faces that moments before expressed deep contemplation are caught in the frantic pace of urban survival. Is this progress? Or, as the title suggests, is it a form of consumption, where one way of life feeds off another? Powaqqatsi forces us to consider the human cost of the global shifts that were accelerating rapidly even then, in the late 80s. What gets lost when ancient rhythms are paved over by the relentless beat of modernity? The questions linger long after the hypnotic visuals fade.

### The Unseen Narrator: Philip Glass's Score

One cannot discuss Powaqqatsi without delving into the monumental score by Philip Glass. If Reggio provides the eyes, Glass provides the soul. His music, drawing heavily on instrumentation and rhythms from the cultures depicted, is inseparable from the imagery. It’s not mere background accompaniment; it’s an active participant, driving the emotional current, sometimes soaring with celebratory energy, other times sinking into mournful drones or building intricate, anxious patterns. The synergy between Reggio’s vision and Glass’s compositions, honed since Koyaanisqatsi, reaches a unique zenith here. It’s a score that feels simultaneously ancient and contemporary, mirroring the film's thematic core. I remember letting the VHS tape run after the picture ended, just soaking in the isolated score track sometimes included on releases – a testament to its standalone power.

### Weaving the World Tapestry

Bringing Powaqqatsi to life was a Herculean effort. Filmed across a dozen countries including Brazil, Egypt, India, Kenya, Nepal, and Peru, the production faced immense logistical challenges. Unlike the more detached, sometimes aerial perspective of its predecessor, Powaqqatsi required intimate access to communities, capturing life at ground level. Interestingly, its ambitious scope was partly enabled by funding secured through Francis Ford Coppola and George Lucas's American Zoetrope studios, demonstrating a belief in Reggio's unique artistic vision even from within the Hollywood system. Reggio's deliberate use of slow-motion wasn't just stylistic flair; it was a conscious choice to grant dignity and focus to movements and labour often overlooked or anonymized in the rapid pace of modern media. The sheer variety of human experience captured feels immense, a testament to the crew's dedication and sensitivity.

### An Enduring Vibration

Compared to the starker, more technologically focused Koyaanisqatsi, Powaqqatsi feels warmer, more organic, yet perhaps even more unsettling in its implications. It’s less about imbalance and more about absorption and transformation. It doesn't offer the immediate, awe-inspiring spectacle of collapsing buildings or frantic cityscapes found in the first film, demanding a different kind of attention from the viewer – patience, empathy, a willingness to engage with rhythm and image over plot. For some viewers back then, accustomed to more conventional narrative structures, it might have felt challenging, even frustrating. But for those willing to surrender to its flow, it offered a profoundly moving and thought-provoking cinematic journey entirely unlike anything else on the video store shelf. It stands as a powerful meditation on culture, change, and the enduring human spirit caught in the globalizing currents of the late 20th century.

Rating: 8.5/10

Justification: While perhaps less immediately iconic than Koyaanisqatsi, Powaqqatsi is a visually stunning and thematically rich film that achieves a powerful synthesis of image and music. Its focus on the human element provides a unique emotional resonance, and its technical execution, especially the cinematography and Philip Glass's culturally infused score, is exceptional. It loses a fraction for being slightly less focused than its predecessor at times, but its ambition and haunting beauty are undeniable.

Final Thought: Decades later, the questions Powaqqatsi raises about globalization, tradition, and the definition of progress feel more relevant, and more urgent, than ever before. It remains a vital piece of cinematic art, a sensory poem that vibrates with the pulse of a world in constant, complex transition.