Some images sear themselves onto the back of your eyelids, don't they? Not the carefully crafted scares of fiction, but the grainy, undeniable horrors pulled straight from the headlines, replayed endlessly on the news until they become a kind of grim wallpaper. The Killing of America doesn't just use that wallpaper; it tears it off the wall, forces you to look at the rot underneath, and dares you to call it anything less than a mirror. Released in 1981, this wasn't a tape you casually picked up next to the comedies; it felt illicit, dangerous, a harsh dose of reality smuggled onto the shelves alongside escapism.

An Unflinching Chronicle of Violence

Directed by Sheldon Renan and co-written and co-directed by Leonard Schrader (brother of the acclaimed Paul Schrader, who penned gritty classics like Taxi Driver), The Killing of America presents itself as a stark examination of the escalating violence in the United States from the 1960s through the late 1970s. Forget narrative arcs or character development; this is a relentless compilation documentary, a barrage of assassinations, riots, murders, and the chilling words of killers themselves. It stitches together newsreel footage, amateur recordings, and police evidence with a cold, almost clinical detachment, narrated with grim authority by Chuck Riley. The effect is overwhelming, designed to shock, yes, but also, perhaps, to numb.

The film opens with stark statistics and quickly plunges into the defining traumas of a generation: the assassinations of JFK, Martin Luther King Jr., and Robert F. Kennedy are shown with the raw immediacy of the original broadcasts. But it doesn't stop there. We witness shootouts, hostage situations, the chaos of riots, and intimate glimpses into the aftermath of unimaginable acts. It's the kind of footage that feels almost profane to watch, yet impossible to turn away from. Remember seeing snippets of this stuff on the nightly news, filtered and contextualized? The Killing of America removes the filters.

More Than Just Shock Value?

Originally financed and released primarily in Japan (where it found a more receptive audience for its bleak portrayal of American society), the film had a notoriously difficult time securing distribution in the US. It’s not hard to see why. Its thesis is brutal: America is devouring itself. The film juxtaposes images of everyday life – parades, suburban streets – with sudden eruptions of extreme violence, suggesting a sickness lurking just beneath the surface. There’s an undeniable power to its approach, using readily available archival material to construct a terrifying narrative. Did the sheer volume of real-life horror presented back then feel like a necessary wake-up call, or just exploitative sensationalism?

The inclusion of interviews with figures like serial killer Ed Kemper, or audio recordings from the likes of David Berkowitz ("Son of Sam"), adds another layer of chilling intimacy. Hearing the perpetrators articulate their thoughts, often with unnerving calmness, is perhaps more disturbing than the graphic imagery. We even see famed Los Angeles coroner Thomas Noguchi, known for his work on high-profile celebrity deaths, discussing the patterns of violence he witnessed. It lends a veneer of authority, but the relentless focus remains squarely on the carnage. This wasn't just reporting; it felt like an indictment, amplified by the grainy, degraded quality of much of the source material seen on VHS, which somehow made the horror feel even more raw and inescapable.

The Mondo Legacy

The Killing of America often gets lumped into the "mondo" film category – sensationalist documentaries focusing on taboo subjects, death, and bizarre cultural practices, a genre popularized by films like Mondo Cane. While it certainly shares the shock tactics, Schrader and Renan arguably aimed for something more pointed: a specific critique of American culture and its relationship with violence, guns, and media saturation. One often overlooked detail is Leonard Schrader’s deep immersion in Japanese culture (he co-wrote Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters with his brother Paul), perhaps influencing the outsider's perspective that permeates the film’s critique of the US.

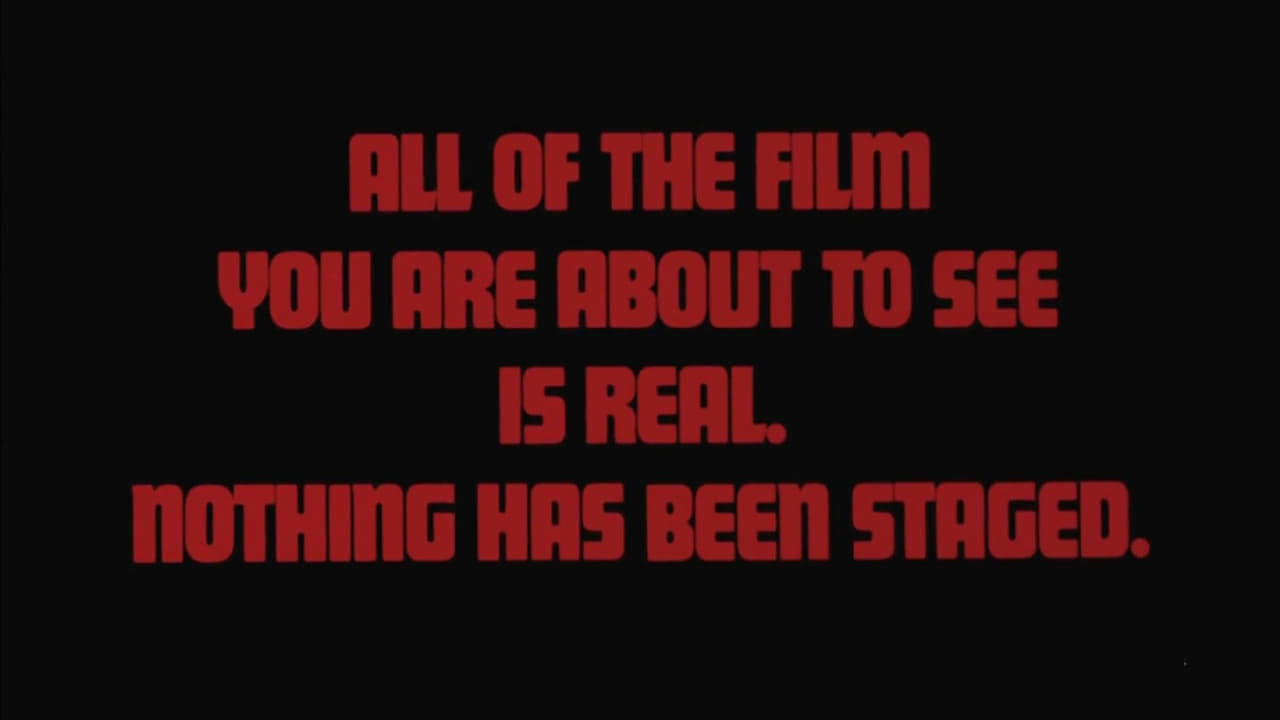

The film’s power lies in its curation of reality. There are no actors, no sets, no special effects – just the unvarnished horror of real events. It forces a confrontation with the darkest aspects of modern history, presented without commentary beyond Riley's somber narration. Watching it today, especially knowing how access to graphic content has changed with the internet, The Killing of America still retains a unique, unsettling power. It feels like a time capsule of anxieties from the late 70s and early 80s, a period grappling with disillusionment and a perceived societal breakdown.

Lasting Chill

The Killing of America is not entertainment. It's a harrowing, often sickening historical document presented as a horror film. It’s the kind of VHS tape that, once watched late at night, might make you double-check the locks and question the shadows outside your window. Its bleakness is absolute, offering no easy answers or comforting resolutions.

Rating: 7/10

Justification: This rating reflects the film's undeniable impact and effectiveness in achieving its disturbing goal. It's a powerful, albeit deeply unsettling, piece of documentary filmmaking that utilizes archival footage to create a potent and chilling portrait of violence. The controversial nature and potentially exploitative aspects prevent a higher score, but its historical significance within the mondo/shockumentary genre and its sheer visceral power are undeniable. It succeeds terrifyingly well at what it sets out to do.

Final Thought: Decades later, The Killing of America remains a brutal artifact from the VHS era – a reminder of a time when confronting such unfiltered reality on your home television felt like peering into a forbidden abyss. Does its central thesis about American violence still hold water today? That's a question that lingers long after the static fades.