It started, famously, with a bet. Werner Herzog, the formidable German director, apparently declared he would eat his own shoe if his friend, a young, determined filmmaker named Errol Morris, ever actually finished his debut feature about pet cemeteries. Well, Morris did finish Gates of Heaven (1978), and Herzog, true to his word (documented in Les Blank's short Werner Herzog Eats His Shoe), did the deed. This almost mythical origin story perfectly encapsulates the unlikely, stubborn, and ultimately profound nature of the film itself – a quiet masterpiece you might have stumbled upon in the 'Documentary' aisle of the video store, nestled between nature films and historical epics, radiating a peculiar, unforgettable aura.

More Than Just Furry Friends

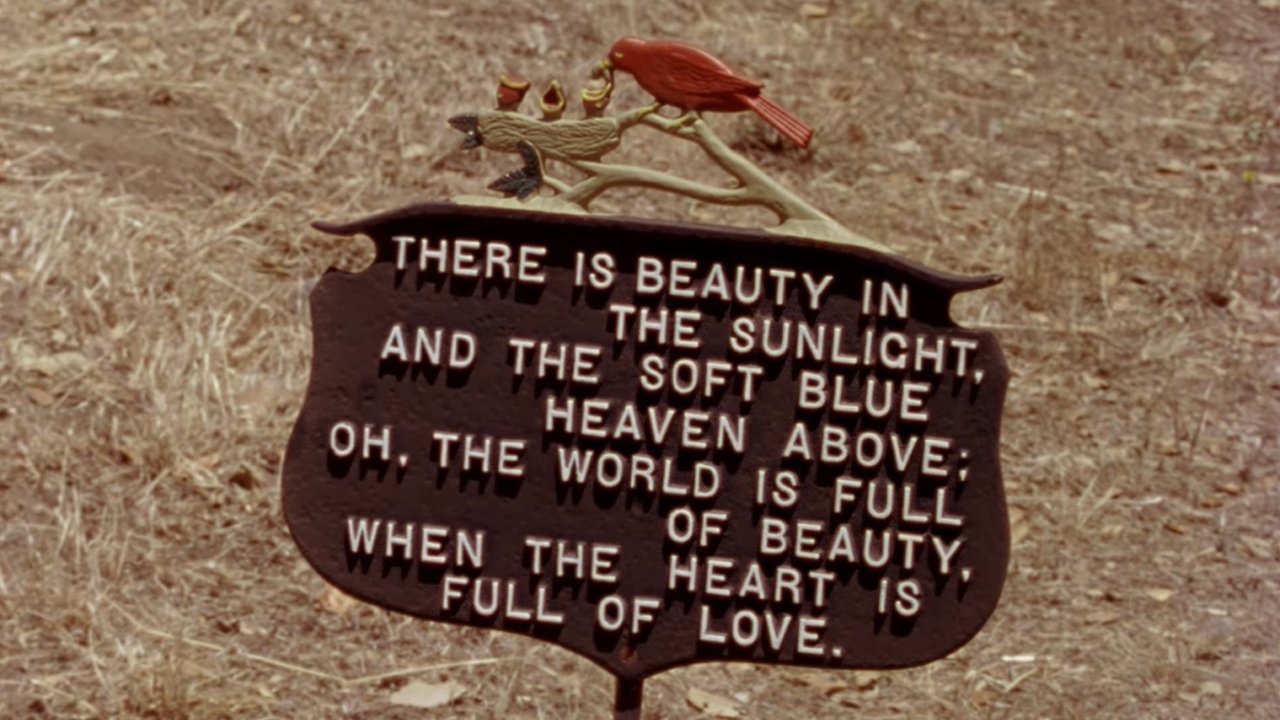

On the surface, Gates of Heaven is simply about two pet cemeteries in Northern California: the struggling Foothill Pet Cemetery, run with earnest if slightly naive ambition by Floyd McClure, and the larger, more corporate Bubbling Well Pet Memorial Park, operated by the Harberts family. But to leave it there is to miss the universe contained within its unassuming frames. Morris doesn't impose a narrative; he listens. He places his camera directly in front of his subjects and lets them talk – about life, death, business, faith, disappointment, and the deep, often inexplicable bonds between humans and their animal companions.

What emerges is less a story about burying pets and more a deeply moving, sometimes darkly funny, meditation on the human condition. We meet people grappling with loss, seeking solace and dignity for creatures they loved unconditionally. Their testimonies, delivered straight to the camera without interviewer interruption (a style Morris would later refine with his invention, the Interrotron), are remarkably candid, sometimes rambling, often poignant, and utterly human. You hear the tremor in a voice recalling a beloved dog, see the quiet pride in a well-maintained grave plot, and sense the weight of dreams deferred in the entrepreneurs trying to make a go of it in the unique business of eternal rest for pets.

The Morris Method Takes Shape

Watching Gates of Heaven today, knowing the celebrated career Errol Morris would forge with films like The Thin Blue Line (1988) and The Fog of War (2003), is fascinating. You see the genesis of his signature style: the patient observation, the seemingly neutral framing that somehow reveals immense depth, the fascination with eccentric individuals and overlooked subcultures. There's no voiceover telling you what to think, no dramatic music cueing your emotions (the score is minimal and effective). Morris trusts his subjects, and he trusts his audience to find the meaning.

The contrast between the two cemetery proprietors is particularly compelling. Floyd McClure, the heart behind the failing Foothill, speaks with a kind of weary optimism, his venture seemingly doomed by factors ranging from rendering plant proximity to, perhaps, his own gentle nature. Then there are the Harberts – Cal, the patriarch, dispensing business philosophy, and his sons, each with their own distinct perspective on the family enterprise and life itself. One son's detour into discussing his motivational speaker aspirations is a standout moment – baffling, hilarious, and strangely touching all at once. These aren't caricatures; they feel like real people navigating their specific corners of the world, captured with an empathetic yet unsentimental eye.

A Foundational Film, Found on Tape

Finding Gates of Heaven on VHS back in the day often felt like uncovering a secret. It wasn't flashy, it wasn't loud, but it lingered. Its power lies in its quiet insistence on the value of every life, every story, no matter how seemingly small or peculiar. It reminds us that grief is grief, whether for a person or a poodle, and that the ways we memorialize our loved ones speak volumes about our own hopes and fears. Morris took a subject ripe for potential mockery and instead delivered a film of profound empathy and subtle insight. He wasn't just documenting pet cemeteries; he was holding a mirror up to the universal human need for connection, remembrance, and a little patch of peace at the end of the road. The film reportedly struggled to find distribution initially, seen as too oddball, but its reputation grew steadily, championed by critics like Roger Ebert who recognized its unique genius early on.

This wasn't a film you rented for explosive action or dazzling special effects. You rented it, perhaps on a whim, maybe intrigued by the box art or a half-remembered recommendation, and found yourself drawn into its unassuming world. It’s a testament to the power of documentary filmmaking to find the extraordinary in the ordinary, a quality that feels particularly resonant when looking back through the haze of nostalgia. It’s a reminder that sometimes the most profound stories are whispered, not shouted.

Rating: 9/10

This near-perfect score reflects the film's groundbreaking approach, its deep empathy, and its lasting impact as a foundational work of modern documentary. Errol Morris didn't just capture interviews; he captured souls, revealing the poignant, absurd, and deeply felt realities of life and loss through the lens of those who care for our departed pets. It’s a film that avoids easy sentimentality yet resonates with genuine emotion, proving that profound truths can be found in the most unexpected places – even a pet cemetery in Napa Valley. It doesn't just show you its subjects; it makes you feel you know them, leaving you contemplating the quiet dignity of remembrance long after the tape stopped rolling.