Okay, settle in, maybe dim the lights a little. Let’s talk about a film that feels less like a movie watched and more like a scent half-remembered, a melody drifting from another era. I’m thinking about Stanley Kwan’s Rouge (1987), a spectral shimmer of a film that haunted the shelves of more discerning video stores back in the day, often nestled between the louder kung fu flicks and neon-drenched thrillers. Finding this tape always felt like uncovering a secret, a whispered story from a Hong Kong rapidly fading even then.

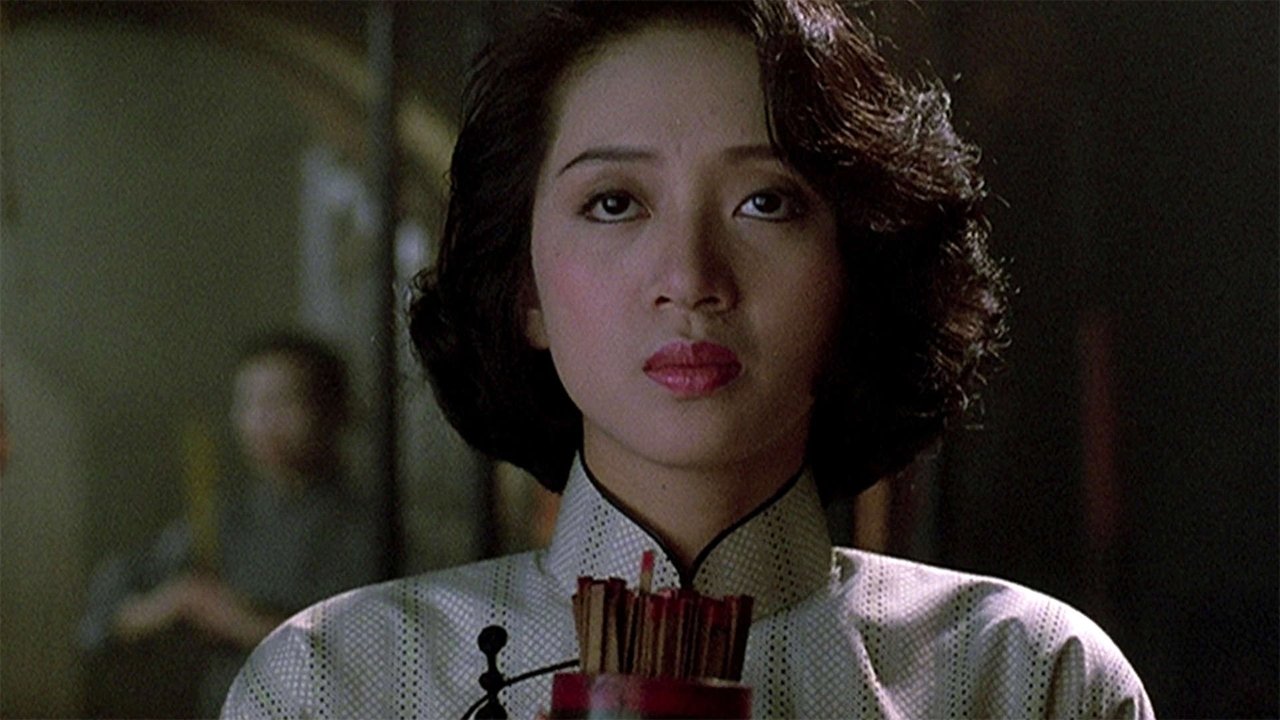

Its opening doesn’t grab you by the lapels; it beckons with a melancholic allure. We meet Fleur (Anita Mui), a high-class courtesan – or "flower girl" – in the opulent, intoxicating world of 1930s Hong Kong. She materializes not just on screen, but seemingly from the very fabric of memory itself, her elaborate cheongsam and painted lips a stark contrast to the world she will soon inhabit. It's a film that begins by immersing us in a lost time, evoked through Kwan’s typically sensitive lens and gorgeous period detail.

A Ghostly Pact, A Modern Search

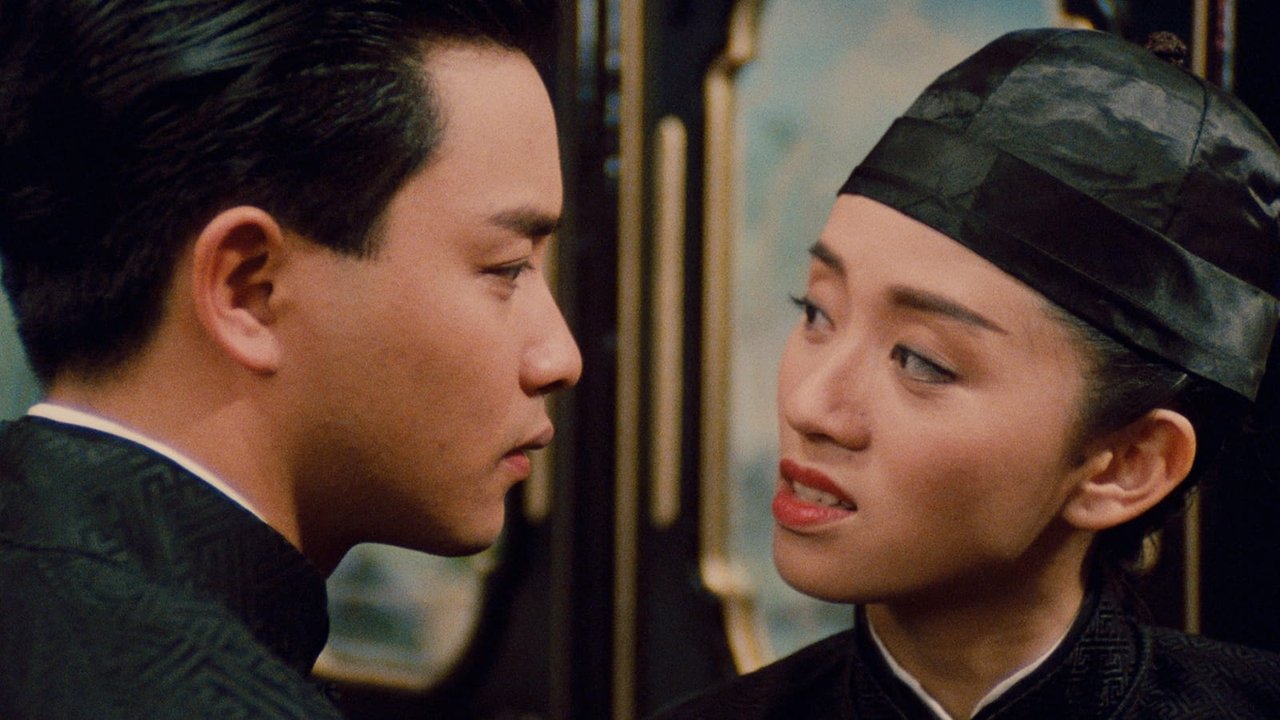

The heart of Rouge beats across two timelines. In the 1930s, Fleur falls deeply, tragically in love with the Twelfth Master Chan Chen-Pang (Leslie Cheung), the scion of a wealthy family. Theirs is a forbidden romance, doomed by class and convention, culminating in a desperate suicide pact meant to reunite them in the afterlife. Fast forward fifty years to 1987, and Fleur – spectral, yet seemingly solid – appears in a bustling, modern Hong Kong newspaper office. She hasn't aged a day, still searching for her lover who failed to meet her in the spirit world. She enlists the help of a bewildered, sympathetic journalist, Yuen (Alex Man), and his cautious girlfriend, Chor (Emily Chu), to place an advertisement and unravel the mystery of Twelfth Master's fate.

This dual narrative isn't just a plot device; it’s the soul of the film. Kwan masterfully contrasts the languid, smoke-filled sensuality of the 1930s teahouses with the pragmatic, sometimes indifferent energy of late-80s Hong Kong. The city itself becomes a character, its changing landscape mirroring the erosion of time and memory. Seeing Fleur navigate the MTR or stand bewildered amidst modern architecture is profoundly moving, highlighting not just her displacement, but perhaps a broader cultural sense of loss many felt in Hong Kong during that period.

Echoes of Stardom and Sorrow

You simply cannot discuss Rouge without dwelling on the performances, particularly those of its two leads, whose real-life destinies now cast an unavoidable, poignant shadow over the film. Anita Mui, already a superstar singer and actress, embodies Fleur with an ethereal grace and a simmering, wounded pride. It's a performance of quiet intensity; her longing and eventual disillusionment are palpable, conveyed often through just a glance or a subtle shift in posture. It’s fascinating to learn that Mui initially hesitated to take the role, feeling it echoed characters she'd played before. Thankfully, after script adjustments (the screenplay was co-written by original novelist Lilian Lee), she delivered what many consider a career-defining performance, rightfully earning her Best Actress at the Hong Kong Film Awards.

Opposite her, Leslie Cheung is equally magnetic as the charming, ultimately weak Twelfth Master. He captures the allure of the aristocratic playboy but crucially doesn't shy away from the character's inherent flaws – his dependence, his lack of resolve. Their chemistry is undeniable, a fragile, hothouse flower of a romance that feels both deeply passionate and tragically unsustainable. Watching them together now, knowing both stars left us far too soon, lends their on-screen pact an almost unbearable weight. The supporting roles of Alex Man and Emily Chu provide the necessary grounding, their modern sensibilities acting as a bridge for the audience into Fleur's extraordinary tale.

More Than Just a Ghost Story

While Rouge is technically a ghost story, the supernatural elements are handled with remarkable restraint. There are no jump scares or elaborate spectral effects. Fleur’s ghostly nature is presented matter-of-factly, allowing the focus to remain squarely on the emotional core: the enduring power, and perhaps the ultimate unreliability, of love and memory. What does it mean to promise eternity? Can love truly transcend death, or even just the slow decay of time and circumstance? The film doesn't offer easy answers, preferring instead to leave these questions lingering, much like Fleur's faint perfume.

Director Stanley Kwan, known for his sensitive portrayals of women and explorations of Chinese history (later seen in works like Center Stage (1991) starring Maggie Cheung), directs with a painterly eye. The cinematography beautifully captures the textures of both eras – the rich, warm tones of the past and the cooler, more functional look of the present. The meticulous production design and costumes aren't just window dressing; they are integral to understanding the characters and their worlds. Even the Cantonese opera motifs woven throughout add layers of cultural resonance and foreshadowing. It’s a film crafted with immense care, reportedly on a budget that, while not shoestring, was modest compared to the action extravaganzas dominating Hong Kong cinema at the time, yet achieved a visual and emotional richness many bigger films lacked.

Lingering Questions in the Fade-Out

Watching Rouge again after all these years, maybe on a format far removed from the original VHS, it retains its haunting power. It’s a film that feels specific to its time and place – a snapshot of Hong Kong grappling with its past and future – yet its themes are timeless. It speaks to anyone who has ever loved, lost, or felt adrift in a changing world. It doesn’t provide the adrenaline rush of many 80s classics, but offers something far more rare and enduring: a profound, melancholic beauty.

Rating: 9/10

This near-perfect score reflects the film's masterful blend of romance, ghost story, and social commentary, anchored by unforgettable performances and Kwan's sensitive direction. The slight deduction acknowledges that its deliberately measured pace might not resonate with viewers seeking faster thrills, but for those willing to surrender to its spell, Rouge is exquisite. It’s a film that stays with you, a quiet ghost whispering about the loves and losses that shape us, long after the screen goes dark. What promises do we make, and which ones truly endure?