The dust never truly settles in the world George Miller built. It hangs thick in the air, gritty between your teeth, mirroring the desolate state of humanity clinging to existence after the fall. And nowhere does that desperation feel more concentrated, more dangerously alluring, than in the chaotic sprawl of Bartertown. Arriving there in Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome (1985) feels less like finding sanctuary and more like stepping into a pressure cooker fueled by methane and salvaged dreams, a place lorded over by a figure as magnetic as she is terrifying.

### Welcome to the Underworld

Forget the relative simplicity of the wasteland skirmishes from The Road Warrior. Beyond Thunderdome plunges Max (Mel Gibson, refining the stoic survivor archetype) into a complex, almost feudal society. Bartertown isn't just a setting; it's a character – a grimy, pulsating organism run on pig feces and brutal pragmatism. The production design here is phenomenal, a junkyard kingdom meticulously crafted, feeling lived-in and dangerously unstable. You can almost smell the decay and desperation wafting off the screen. It's a vision of post-apocalyptic civilization that felt disturbingly plausible back on that grainy VHS tape flickering in the dark.

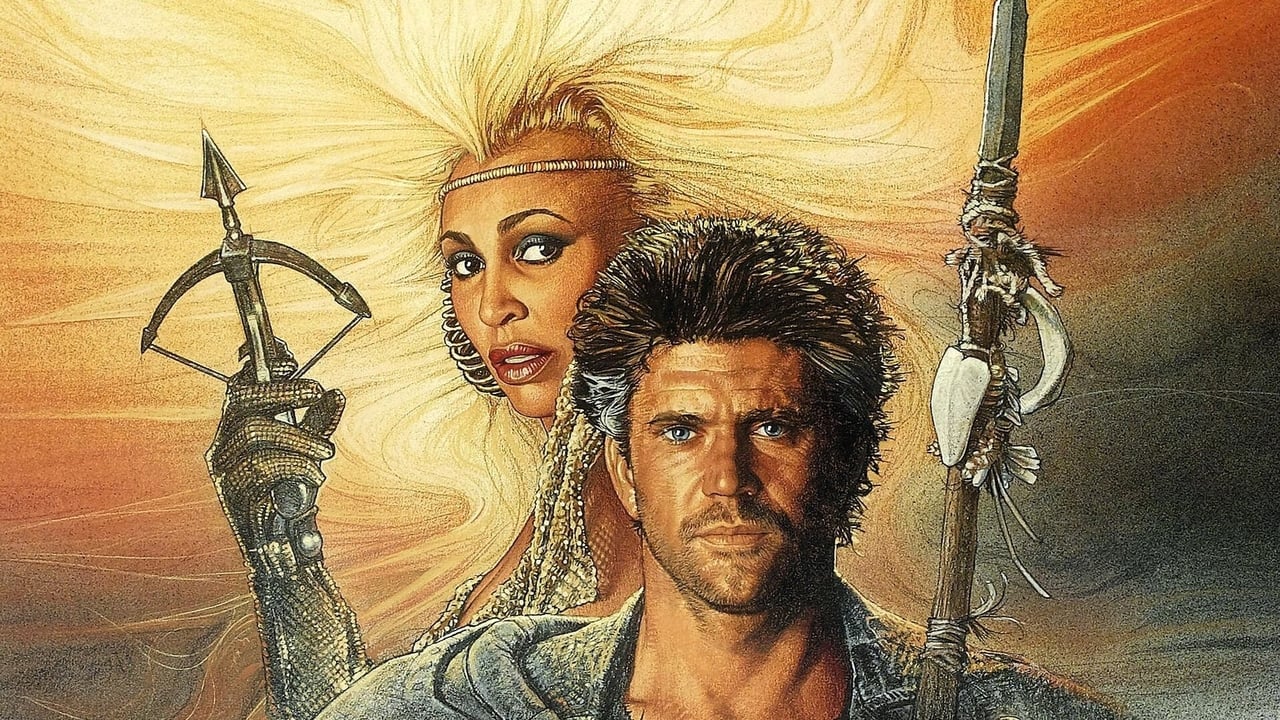

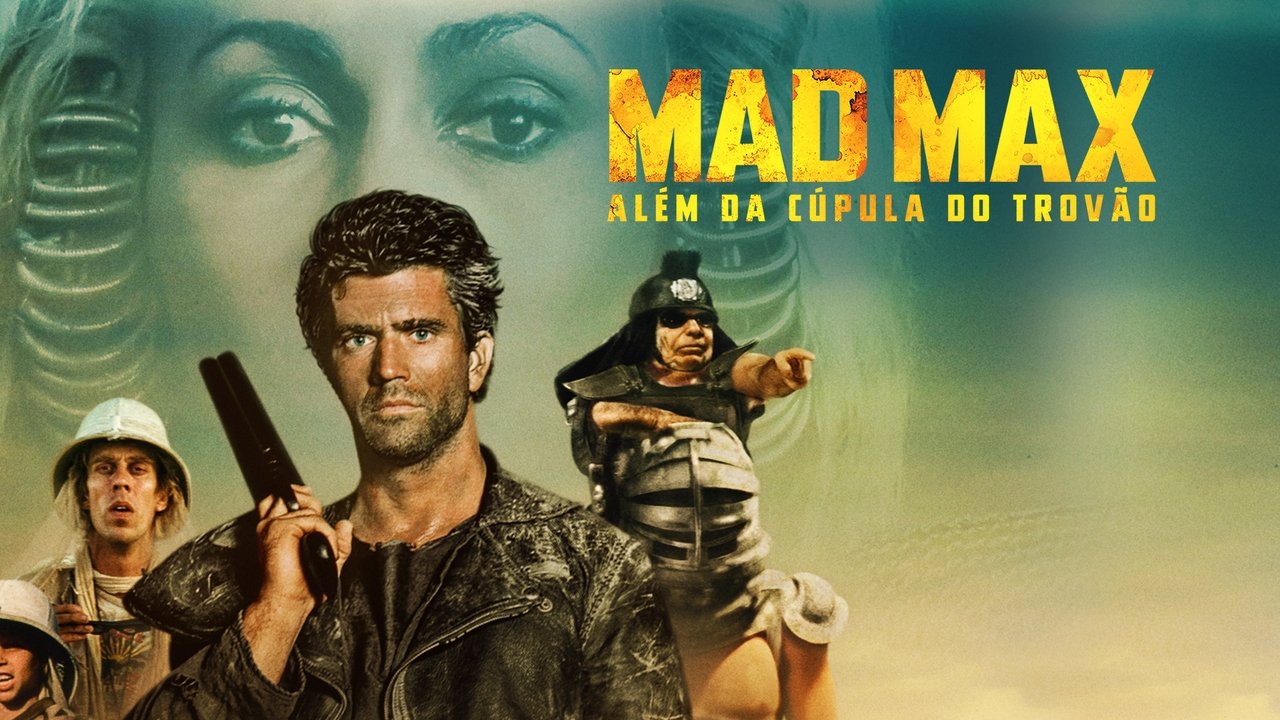

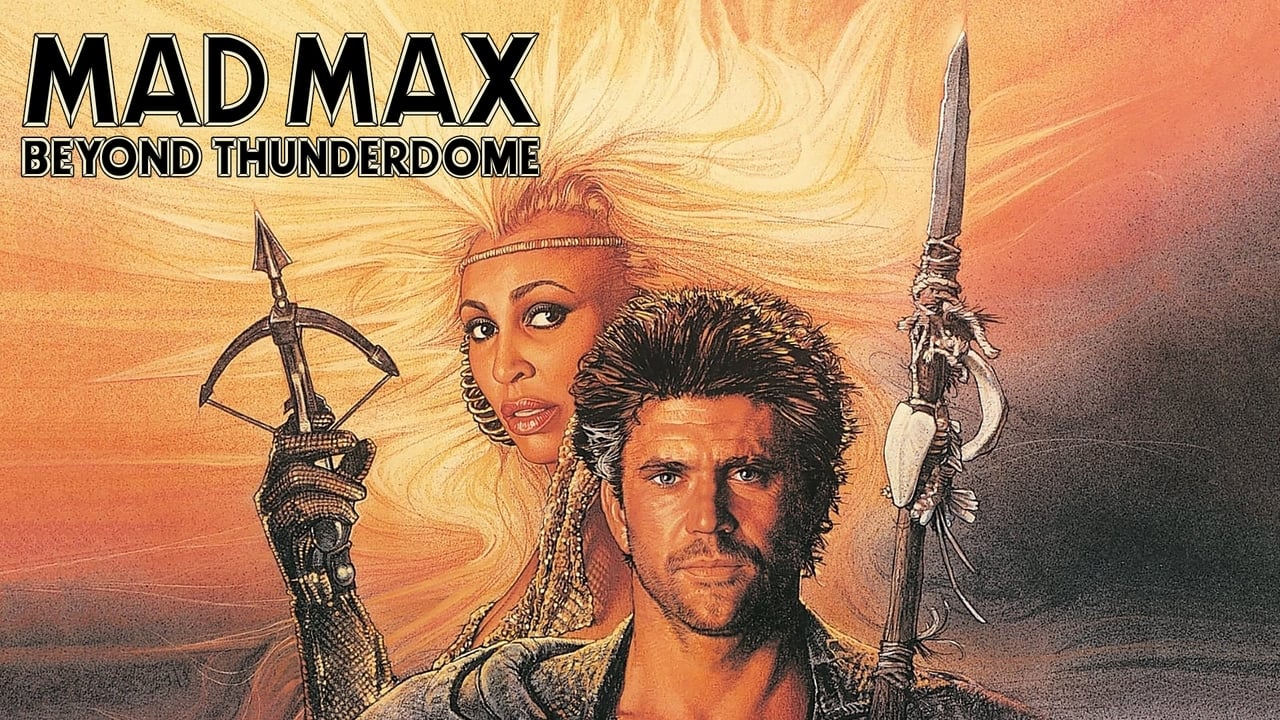

At its heart sits Aunty Entity, brought to life with electrifying charisma by the legendary Tina Turner. Stepping onto the scene like a wasteland queen, clad in that iconic chainmail dress (which reportedly weighed a staggering 55kg!), Turner doesn't just play a role; she commands the screen. She saw something primal and powerful in Aunty, a survivor who built an empire from scrap, embodying the film's central theme: even in the ruins, order – however harsh – will try to assert itself. Turner wasn't just stunt casting; she was Aunty Entity, and her presence, alongside her powerhouse contribution to the soundtrack with "We Don't Need Another Hero," became instantly iconic.

### Two Men Enter...

And then there's the Thunderdome itself. "Two men enter, one man leaves." Has any movie tagline ever burrowed so deeply into the pop culture consciousness? The arena, a giant metal cage where disputes are settled with primal violence while combatants bounce on elastic tethers, is pure 80s spectacle. It’s brutal, inventive, and slightly absurd – a gladiatorial contest for the gasoline age. Watching Max face the hulking Blaster, controlled by the diminutive Master (played brilliantly by veteran actor Angelo Rossitto and Paul Larsson respectively), feels like witnessing a bizarre, high-stakes circus act. The fight choreography, integrating the bungee cords and crude weaponry, remains a standout piece of action design. It’s visceral, kinetic, and unforgettable – the kind of scene you’d rewind the tape to watch again immediately.

Behind the scenes, the film carries a layer of melancholy. George Miller was reeling from the tragic death of his friend and producing partner Byron Kennedy in a helicopter crash during location scouting. Understandably hesitant to return to the demanding world of Mad Max, he brought in theatre director George Ogilvie to co-helm the project. Ogilvie focused heavily on the performances and dramatic elements, particularly the scenes involving the children, allowing Miller to concentrate on the complex action sequences. Some say this collaboration, born from tragedy, contributed to the film's slightly different, perhaps more hopeful, tone compared to its predecessors.

### A Shift in the Sands

The film famously splits into two distinct halves after Max's exile from Bartertown. His discovery of "The Crack in the Earth," a hidden oasis populated by a tribe of children and teenagers descended from plane crash survivors, marks a significant tonal shift. Filmed amidst the striking, otherworldly landscapes of Coober Pedy in South Australia, these sequences introduce a sense of myth and nascent legend. The children, with their cargo cult mentality and fragmented language ("Captain Walker," "Tomorrow-morrow Land"), see Max as a prophesied saviour. It’s here the film diverges most sharply from the grim nihilism of The Road Warrior, embracing themes of hope, community, and the burden of legacy.

This shift remains a point of debate among fans. Does the introduction of the children soften the Mad Max universe too much? Or does it add a necessary layer of humanity and emotional depth? Personally, I always found the contrast fascinating. It expands the world, suggesting different forms of survival beyond brutal pragmatism. Seeing Bruce Spence return as Jedediah, now with a son, also provides a neat link back while reinforcing the idea of time passing and new generations emerging even in this harsh world. And let's be honest, the final chase sequence, while perhaps not quite matching the relentless intensity of The Road Warrior's tanker pursuit, is still a thrilling piece of vehicular mayhem orchestrated with Miller's signature flair.

### Legacy Beyond the Dome

Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome might be the most divisive entry in the original trilogy. It lacks the raw, punk energy of the first film and the relentless, visceral perfection of the second. Its ambition is undeniable, though, expanding the lore and venturing into more complex thematic territory. The world-building is richer, the characters arguably more colourful (Aunty Entity, Master Blaster), and its iconic moments – the Thunderdome, Bartertown, Tina Turner's performance and music – are deeply ingrained in 80s pop culture. The score by Maurice Jarre (Lawrence of Arabia, Doctor Zhivago) lends an epic, almost operatic quality that underscores the film's grander scale. While its budget (around $10 million) yielded a solid box office return ($36 million worldwide), it perhaps didn't quite capture the zeitgeist in the same way The Road Warrior did, receiving a more mixed critical reception at the time.

It might not be the lean, mean fighting machine that The Road Warrior was, but Beyond Thunderdome offers something else: a sprawling, ambitious, and oddly affecting vision of life after the end of the world. It dared to suggest that maybe, just maybe, there was something more to fight for than just the next tank of gas.

Rating: 7.5/10

Justification: While the tonal shift with the children can feel abrupt and it doesn't quite hit the action highs of The Road Warrior, Beyond Thunderdome excels in world-building, iconic character creation (Tina Turner is unforgettable), and memorable set pieces like the Thunderdome itself. Its ambition, visual creativity, and undeniable cultural impact earn it a strong score, even if it’s the slightly eccentric middle child of the original trilogy.

Final Thought: It's the Mad Max film that dared to hope, wrapped in leather, dust, and the unforgettable echo of "Two men enter, one man leaves." A weird, wonderful, and essential piece of 80s post-apocalyptic cinema.