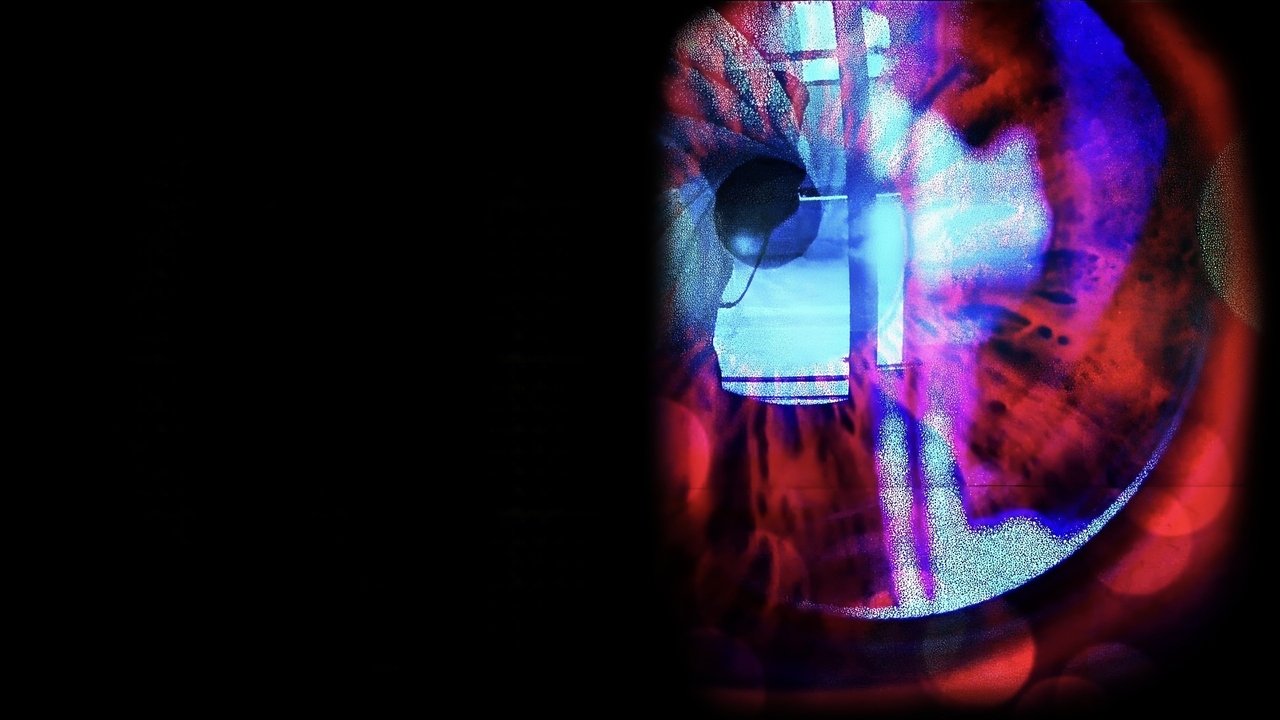

The eye lingers. That's where it starts, doesn't it? Not just with Jake Scully, the perpetually unlucky actor at the heart of Brian De Palma's slick, sleazy masterpiece, Body Double (1984), but with us, the viewers. De Palma understands the inherent voyeurism of cinema, the thrill and transgression of watching unwatched, and he weaponizes it here, crafting a film that feels like peering through the wrong window late at night, knowing you shouldn't look, but unable to turn away. It’s a film that crawls under your skin, less through outright fright and more through a pervasive, uncomfortable intimacy with darkness.

Peering into the Abyss

We meet Jake Scully (Craig Wasson) at rock bottom. An attack of crippling claustrophobia costs him a role in a low-budget vampire flick (the wonderfully meta "Vampire's Kiss" sequences bookend the film), and he returns home only to find his girlfriend cheating. Adrift and desperate, he encounters fellow actor Sam Bouchard (Gregg Henry, radiating smug charm), who offers a lifeline: a luxurious, ultra-modern house-sitting gig in the Hollywood Hills. The catch? The house comes equipped with a telescope permanently aimed at the window of a beautiful neighbor, Gloria Revelle, who performs a nightly erotic dance. Sam encourages Jake to watch, framing it as harmless obsession. But in De Palma's world, obsession is never harmless.

This setup, echoing Hitchcock's Rear Window but drenched in 80s excess and cynicism, immediately establishes the film's unnerving tone. De Palma, ever the stylist, uses long, gliding camera movements and slow, deliberate zooms that mimic the act of scopophilia, pulling us complicitly into Jake's gaze. The house itself, the iconic Chemosphere designed by John Lautner, feels like an alien spacecraft landed in the hills – isolated, futuristic, and the perfect panopticon for Jake's burgeoning fixation. You can almost feel the cool glass of the telescope against your eye, the illicit thrill mixing with a growing sense of dread.

Style, Shock, and Controversy

Body Double arrived hot on the heels of criticism leveled at De Palma for the violence in Dressed to Kill (1980), and it feels like a deliberate, almost defiant doubling-down. This isn't just a thriller; it's an erotic thriller that pushes boundaries with gusto. The infamous sequence set to Frankie Goes to Hollywood's pulsating "Relax" is pure, unadulterated De Palma – audacious, provocative, and technically dazzling. Reportedly, De Palma himself directed the music video for "Relax," forging a symbiotic link between the song's rebellious energy and his film's transgressive themes.

Then there's the violence. The notorious drill murder scene is brutal and unflinching, causing significant controversy and battles with the MPAA, leading to an initial X rating before cuts were made. It’s a sequence designed to shock, yes, but it also serves the film’s commentary on the exploitation inherent in the images Jake (and by extension, the audience) consumes. De Palma isn't just showing violence; he's interrogating the gaze that finds titillation even in horror. Does that make it any less uncomfortable? Perhaps not, and that discomfort feels entirely intentional.

It's impossible to discuss the film's impact without mentioning Melanie Griffith as Holly Body, the porn star Jake seeks out to help unravel the mystery. Griffith, in a career-making turn, imbues Holly with a surprising blend of street-smart confidence and vulnerability. She navigates the absurdity of the adult film world (providing some welcome, darkly ironic humor) while grounding the increasingly convoluted plot. It’s a performance that perfectly captures the film's blend of artifice and unexpected heart.

Echoes in the Tape Hiss

Watching Body Double on VHS back in the day felt like handling contraband. Its reputation preceded it, whispered about in video stores. It wasn't just the sex and violence; it was the film's sheer, unapologetic style and its cynical take on Hollywood illusion. Pino Donaggio's score, a frequent and brilliant collaborator with De Palma, perfectly complements the visuals, swirling between lush romanticism and jarring suspense, mirroring Jake's descent.

Interestingly, for all its slickness and controversy, the film wasn't a box office smash, pulling in just under $9 million against its $10 million budget. Yet, like so many distinctive visions from the era, it found its true audience on home video, becoming a cult classic whispered about among cinephiles and fans of provocative filmmaking. You have to admire De Palma's nerve, consciously riffing on Hitchcock (Vertigo's themes of obsession and constructed identity are just as present as Rear Window's voyeurism) while pushing the envelope far beyond what the Master of Suspense would likely have dared in his time. And spare a thought for Craig Wasson, who reportedly battled genuine claustrophobia while filming the harrowing sequence where Jake finds himself trapped underground – art imitating life, perhaps?

Final Focus

Body Double remains a divisive film. Some dismiss it as cynical, misogynistic style over substance. Others hail it as a brilliant, self-aware commentary on voyeurism, filmmaking, and the seductive dangers of looking. It’s undeniably excessive, occasionally ludicrous, but always visually arresting and thematically provocative. De Palma throws everything at the screen – split-diopter shots, elaborate tracking sequences, dreamlike logic – creating an experience that’s both exhilarating and deeply unsettling. It’s a film that doesn't just show you darkness; it makes you feel complicit in it. Doesn't that feeling linger, even now?

Rating: 8/10

This score reflects Body Double's audacious style, technical mastery, and its unforgettable, provocative nature. It’s a quintessential De Palma experience – flawed, perhaps, in its plotting and controversial in its themes, but undeniably powerful and visually stunning. It earns its high marks for sheer directorial bravura and its lasting impact as a standout, boundary-pushing thriller of the 80s VHS era, warts and all. A challenging, cynical, but utterly magnetic piece of filmmaking that still has the power to make you squirm.