It arrives like a transmission from another time, another planet almost. Watching D. A. Pennebaker's Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars today, especially if you first encountered it on a well-worn VHS tape pulled from the back shelves of a rental store, feels less like watching a concert film and more like bearing witness to a fleeting, electric moment captured just before it vanished forever. The grain of the film stock, the sometimes-murky lighting – these aren't flaws; they feel integral, pulling you into the sweaty intimacy of London's Hammersmith Odeon on that fateful night, July 3rd, 1973.

An Alien Landing, Captured on Film

Pennebaker, already a legend for his fly-on-the-wall work with Bob Dylan in Don't Look Back (1967) and the vibrant tapestry of Monterey Pop (1968), brought his signature cinéma vérité style here. There’s a raw immediacy, a sense of being there, shoulder-to-shoulder with the mesmerized audience. This wasn't a pre-planned, multi-camera spectacle in the way concert films often became later. Reportedly, Pennebaker had minimal prep time and faced significant challenges, particularly with the low stage lighting. He had to work with what was available, using fast film stock that resulted in the grainy, almost dreamlike texture. Yet, doesn't this visual imperfection somehow heighten the sense of reality, of capturing something authentic and untamed? It feels less mediated, more like a direct feed from the event itself. Budget constraints, apparently stemming from RCA Records' initial hope for a simpler TV special, also meant fewer cameras than ideal, forcing Pennebaker and his crew to make crucial choices about what to capture, lending the final film an almost voyeuristic intensity.

The Starman Commands the Stage

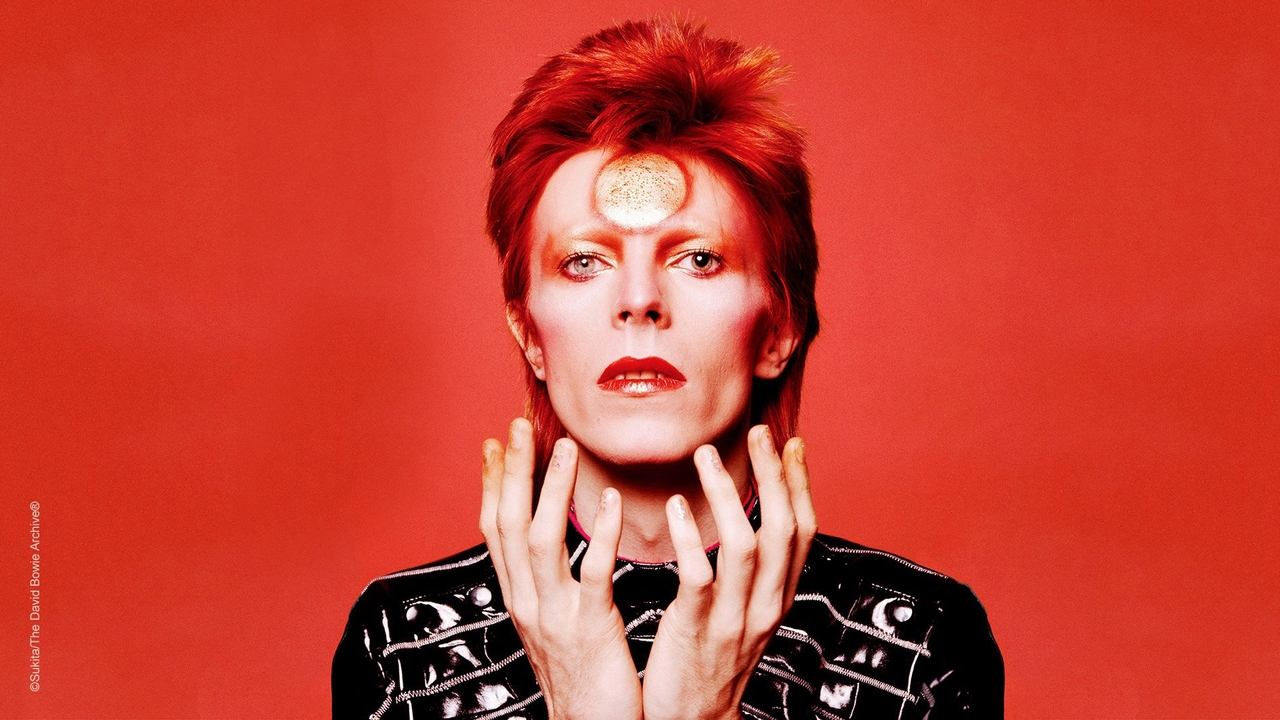

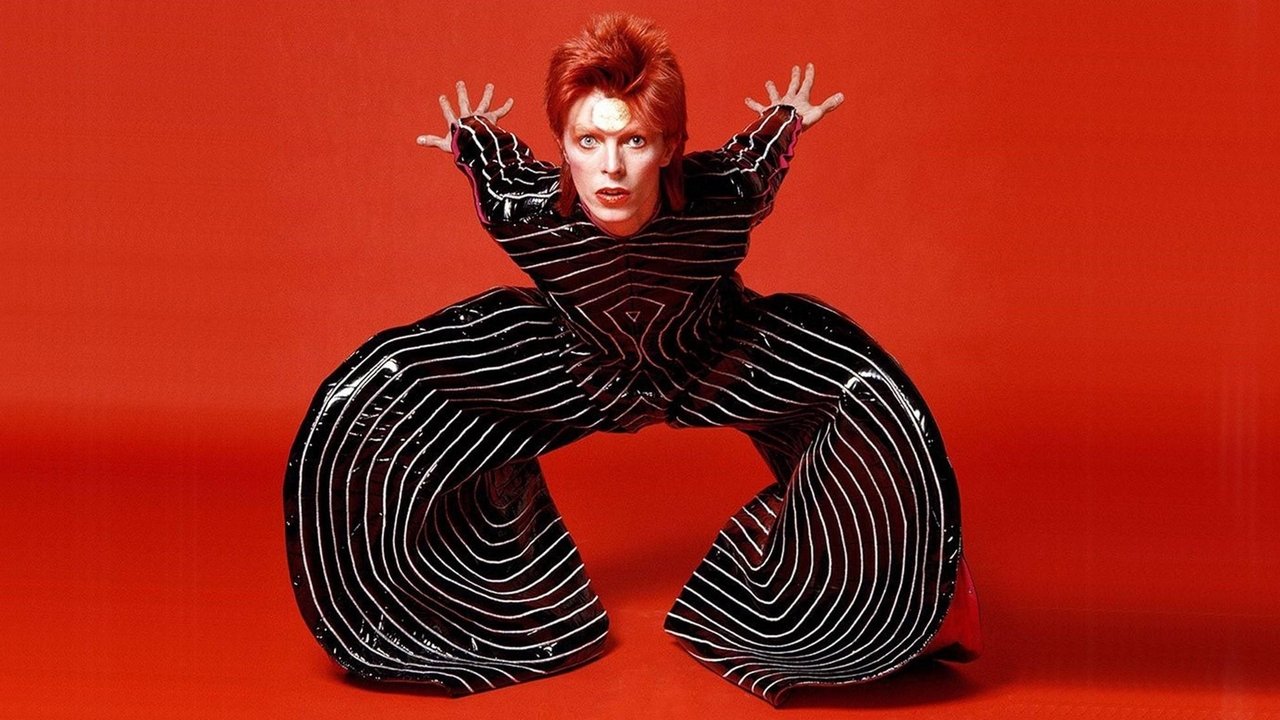

And at the centre of it all, there’s David Bowie. This isn't just a musician performing songs; it's an artist fully inhabiting a creation. The Ziggy Stardust persona – the flame-red hair, the otherworldly Kansai Yamamoto costumes, the makeup, the calculated androgyny – feels less like an act and more like a vessel Bowie channelled. His performance is magnetic, oscillating between charismatic rock god swagger and moments of startling vulnerability or alien detachment. Watching him command the stage, particularly during numbers like "Moonage Daydream" or "Suffragette City," you understand why Ziggy became such a phenomenon. He wasn't just singing about being an alien; for those 90 minutes, he was one, a creature of pure rock and roll theatre beamed down to electrify a generation. It’s a performance of total commitment, pushing boundaries of gender expression and stagecraft in ways that still feel potent.

The Spiders and the Shockwave

Of course, Ziggy wasn't alone. The Spiders from Mars – the sublimely talented Mick Ronson on guitar, Trevor Bolder on bass, and Mick 'Woody' Woodmansey on drums – were the engine driving the spaceship. Ronson, in particular, is a revelation here. His guitar work is legendary, a perfect foil to Bowie’s theatricality – gritty, glamorous, and technically brilliant. His visual presence, coolly confident beside the fiery Ziggy, is just as crucial. Pennebaker’s camera rightly spends considerable time on Ronson’s virtuosic playing, capturing the symbiotic musical energy between him and Bowie.

Which makes the film’s climax all the more staggering. Bowie’s infamous announcement before the final encore ("Not only is it the last show of the tour, but it's the last show that we'll ever do.") reportedly came as a complete shock to Bolder and Woodmansey. You can almost feel the air go out of the room, the ripple of disbelief through the audience and, one imagines, the band itself. Pennebaker captures this pivot point perfectly – the end of Ziggy, the end of the Spiders, the end of an era, preserved forever on film.

From Celluloid Ghost to VHS Staple

The journey of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars to our VCRs was almost as dramatic as the concert itself. Though filmed in '73, post-production woes, particularly surrounding the sound mix, delayed its release significantly. The soundtrack album appeared in 1979, but the film didn't get a proper (albeit limited) theatrical run until 1983. Apparently, initial sound mixes were considered poor, requiring later rescue work by legendary Bowie producer Tony Visconti to bring the audio up to scratch for subsequent releases. This delay, however, perhaps allowed the legend to grow, making its eventual arrival on home video feel even more momentous for fans who had only heard whispers of this final, legendary performance. It became one of those essential tapes, a portal back to a moment of pure, unadulterated rock and roll myth-making. (And for the trivia hunters: yes, guitar god Jeff Beck joined the band onstage for a couple of numbers, including a scorching "Jean Genie/Love Me Do" medley. His appearance was famously cut from some initial releases at his request, only to be restored later, adding another layer to the film's fascinating history).

The Verdict

Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars isn't the slickest concert film ever made. Its technical imperfections – the grain, the sometimes challenging audio, the occasionally frantic camerawork born from necessity – are readily apparent. But these elements don't detract; they contribute to its power, its authenticity, its feeling of capturing lightning in a bottle. It’s a vital document of a pivotal moment in music history, showcasing an artist at the peak of a very specific, potent creation, backed by an incredible band, all captured with vérité immediacy by a master documentarian. The performances are electric, the atmosphere palpable, and the sense of witnessing the end of something special is deeply resonant.

Rating: 9/10

Its historical significance and the sheer power of Bowie and Ronson are undeniable. The technical limitations prevent a perfect score, but they paradoxically enhance its raw, immediate feel, making it essential viewing. It’s more than a concert; it’s a time capsule preserving the brief, blazing life of a rock and roll alien. What lingers most isn't just the music, but the ghost of that incandescent persona, flickering on the screen, forever saying goodbye.