Ah, the deceptive simplicity of a summer holiday. Sun-drenched beaches, the gentle rhythm of waves, the promise of fleeting romance... But linger a moment longer on that Normandy shore, amidst the seemingly carefree conversations, and you'll find the intricate, often contradictory, heart of Éric Rohmer's Pauline at the Beach (1983). This wasn't your typical neon-soaked 80s blockbuster vying for attention on the video store shelf; finding a Rohmer film often felt like uncovering a secret, a quieter, more observant window onto human nature tucked between the action heroes and slasher villains.

Sunlight and Shadow Play

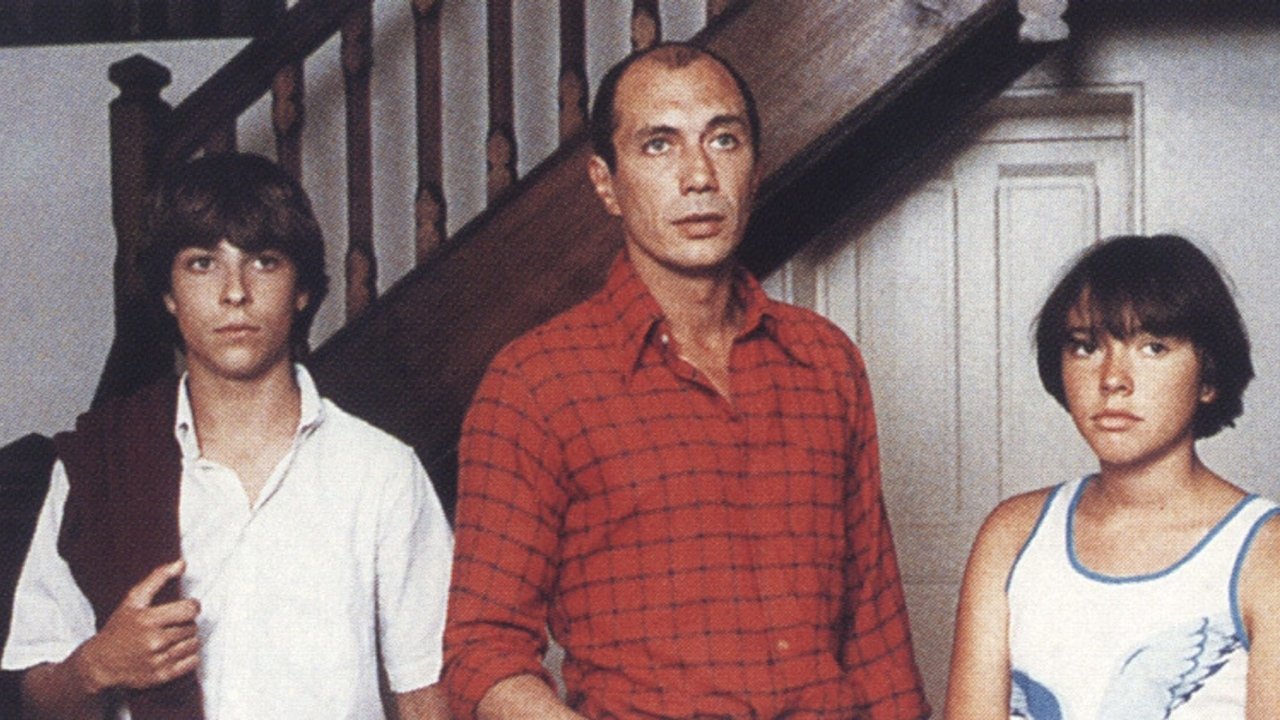

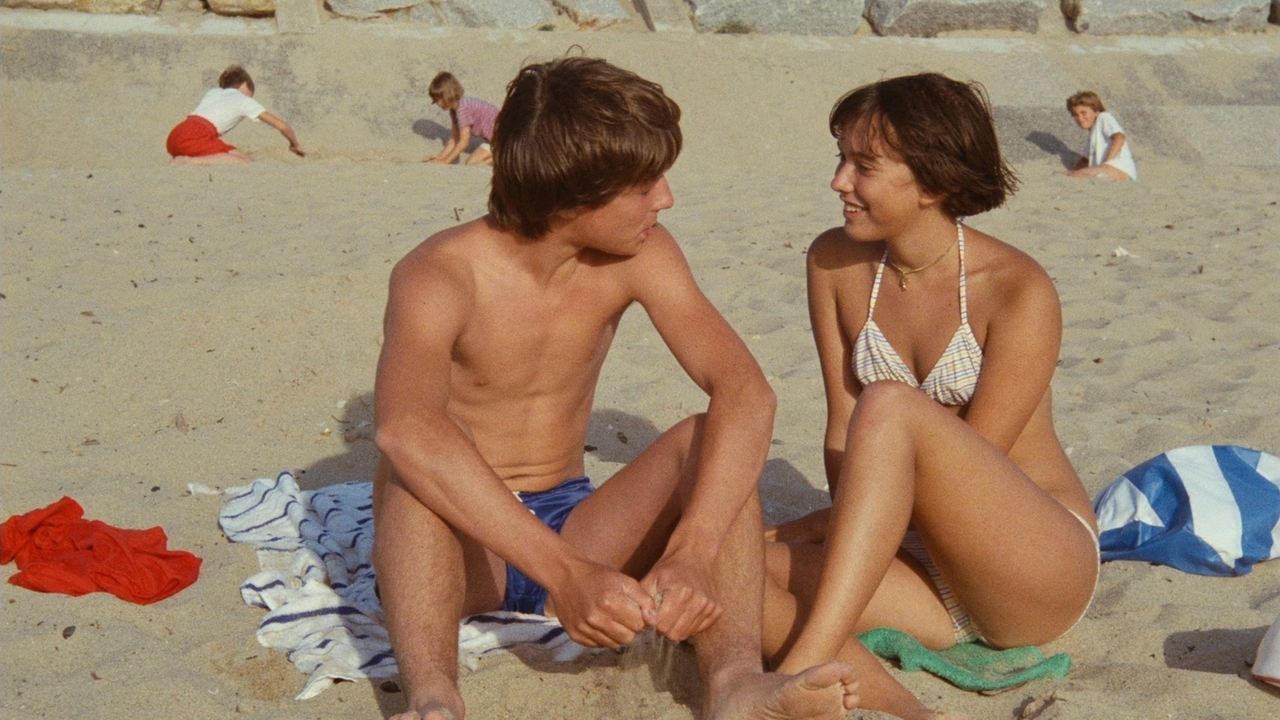

The premise appears straightforward: fifteen-year-old Pauline (Amanda Langlet, in a remarkably natural debut) spends the last weeks of summer at a family beach house with her older, recently divorced cousin Marion (Arielle Dombasle). Marion, effortlessly glamorous and articulate about her desire for consuming passion, quickly attracts the attention of two men: the earnest, slightly melancholic Pierre (Pascal Greggory) and the incorrigible ethnologist/lothario Henri (Féodor Atkine). Pauline, meanwhile, cautiously observes the adults' tangled games while experiencing her own tentative connection with the young Sylvain (Simon de La Brosse).

Rohmer, a master craftsman often associated with the later ripples of the French New Wave, isn't interested in grand dramatic gestures. Instead, he crafts a delicate ecosystem of conversations, misunderstandings, and subtle shifts in allegiance. The beauty of the Normandy coast, captured with Rohmer’s characteristic preference for natural light and uncluttered framing by cinematographer Néstor Almendros (who also shot Days of Heaven), becomes a sun-dappled stage for the decidedly less picturesque aspects of human interaction: casual betrayal, self-deception, and the yawning gap between professed ideals and actual behaviour.

The Proverbial Truth

Part of Rohmer's "Comedies and Proverbs" series (each film loosely illustrating a saying – this one being Chrétien de Troyes' "He who talks too much does himself harm"), Pauline at the Beach excels in exposing the folly and hypocrisy often lurking beneath sophisticated pronouncements about love and life. Marion desires a love that "sets her ablaze," yet settles for the path of least resistance with the manipulative Henri. Pierre pines openly for Marion, his sincerity becoming almost burdensome. Henri, perhaps the most honest in his dishonesty, weaves justifications for his casual affairs.

It’s through the eyes of Pauline that the adults' posturing is most sharply revealed. Amanda Langlet imbues her with a quiet intelligence and an almost unnerving clarity. She listens, she processes, and her simple, direct questions often cut through the layers of rationalization the older characters construct. Her observation that adults "complicate everything" feels less like teenage naiveté and more like a profound truth exposed by the film's events. It's a performance of remarkable subtlety, especially considering Langlet was around Pauline’s age during filming; Rohmer had a knack for eliciting incredibly authentic portrayals from young actors.

A Different Kind of Rewind

Watching Pauline at the Beach today evokes a specific kind of nostalgia – not necessarily for the film itself being a ubiquitous rental, but for the era when video stores offered such diverse cinematic encounters. Tucked away perhaps in a "Foreign Films" section, it represented a different texture, a different pace. This wasn't a movie powered by explosions or synth scores, but by the rhythm of dialogue and the quiet intensity of human observation. Rohmer famously favoured extensive rehearsal, allowing his actors to inhabit the dialogue until it felt utterly spontaneous, a technique evident in the film's effortless flow. The budget was modest, shot largely on location, relying on the power of performance and the inherent drama of the situation rather than elaborate set pieces.

The film doesn't shy away from the messiness. A pivotal misunderstanding, born from Henri’s casual deceit and amplified by others' assumptions, forms the narrative crux. It’s frustrating, almost agonizingly so, to watch unfold, yet it feels undeniably true to the ways miscommunication and self-interest can poison relationships. Arielle Dombasle is captivating as Marion, embodying a certain kind of intellectualized sensuality that ultimately proves fragile. Pascal Greggory perfectly captures Pierre's wounded romanticism, making his eventual bitterness understandable, if not entirely sympathetic.

Final Thoughts on the Shore

Pauline at the Beach isn't concerned with providing easy answers or neat resolutions. It presents a slice of life, a summer microcosm where desires clash, words betray actions, and innocence navigates a landscape of adult complexities. It requires patience, an appreciation for nuance, and a willingness to engage with characters who are deeply flawed yet recognizably human. For those accustomed to the fast cuts and high stakes of mainstream 80s cinema, Rohmer's deliberate pacing and philosophical underpinnings might feel like shifting gears, but the journey is richly rewarding. It lingers, much like the memory of a summer holiday, leaving you pondering the masks people wear and the truths they choose to ignore.

Rating: 8.5/10 - This score reflects the film's masterful subtlety, its insightful exploration of human relationships, and the authentic performances Rohmer elicits. It's a near-perfect execution of its specific artistic goals, a benchmark in dialogue-driven, observational cinema. It loses a fraction perhaps only because its deliberate, talk-heavy nature won't resonate universally, but for those attuned to its frequency, it's brilliant.

Lingering Question: After the tide goes out on Pauline's summer, what wisdom does she truly take away from the adults' complicated games, and how much clarity is lost when memory smooths the edges?