The perpetual rain slicks the streets of Los Angeles, 2019, reflecting neon signs hawking off-world colonies and synthesized snakes. Even through the flickering static of a well-worn VHS tape, the oppressive weight of that future felt chillingly real, didn't it? Blade Runner wasn't just another sci-fi flick filling the shelves at the video store; it was an experience, a descent into a future so beautifully rendered yet so profoundly melancholic, it seeped into your bones long after the credits rolled and the VCR clicked off.

### Tears in Rain-Soaked Noir

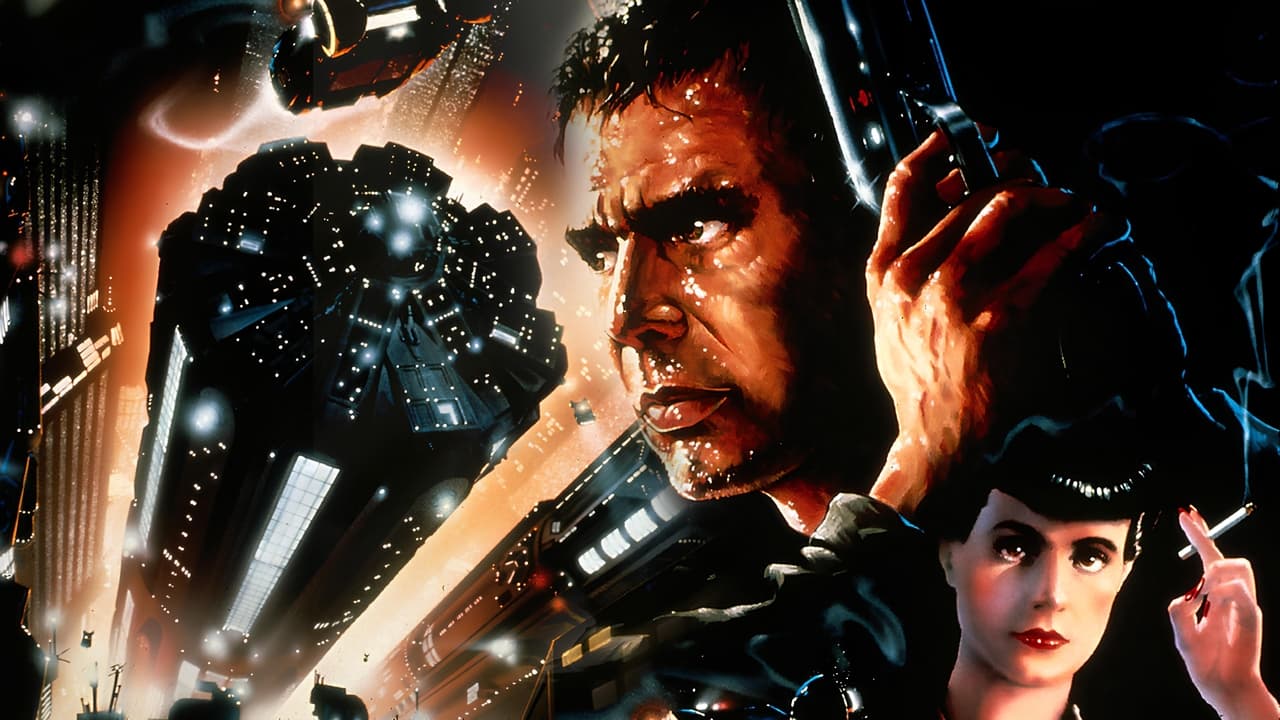

Forget hyperspace dogfights and laser shootouts. Ridley Scott, hot off the suffocating terror of Alien (1979), delivered something entirely different here: a brooding, atmospheric detective story wrapped in the skin of science fiction. This is pure future-noir. We have Rick Deckard (Harrison Ford, channeling a weariness far removed from Han Solo's swagger), the burned-out Blade Runner tasked with 'retiring' rogue Replicants – androids virtually indistinguishable from humans. We have the enigmatic Rachael (Sean Young), a Replicant who believes she's human, embodying the classic femme fatale archetype shrouded in synthesized memories. And looming over it all is the Tyrell Corporation, a monolithic entity playing God from its pyramid headquarters, a chilling premonition of corporate power run rampant. Scott masterfully uses shadow, smoke, and that relentless rain to create a claustrophobic, decaying world that feels both futuristic and strangely ancient.

### More Human Than Human

While Deckard hunts, the hunted steal the show. The Nexus-6 Replicants – sophisticated, strong, but cursed with a four-year lifespan – aren't just malfunctioning machines. They're beings desperate for more life, grappling with implanted memories and burgeoning emotions. Their quest is primal, tragic, and deeply unsettling. Rutger Hauer delivers an all-time iconic performance as Roy Batty, the leader of the fugitive Replicants. He’s menacing, intelligent, poetic, and ultimately, heartbreakingly human in his final moments. That famous "Tears in Rain" monologue? Legend has it Hauer himself significantly altered and shortened the scripted lines on the day of shooting, condensing pages of dialogue into that haunting, unforgettable epitaph delivered with visceral power. It's a moment that elevates the film beyond genre trappings into philosophical territory, forcing us to question what truly defines life and consciousness. Doesn't Batty's raw desire for existence feel more genuine than the cold indifference of many humans in this world?

### Building a Future We Still Recognize

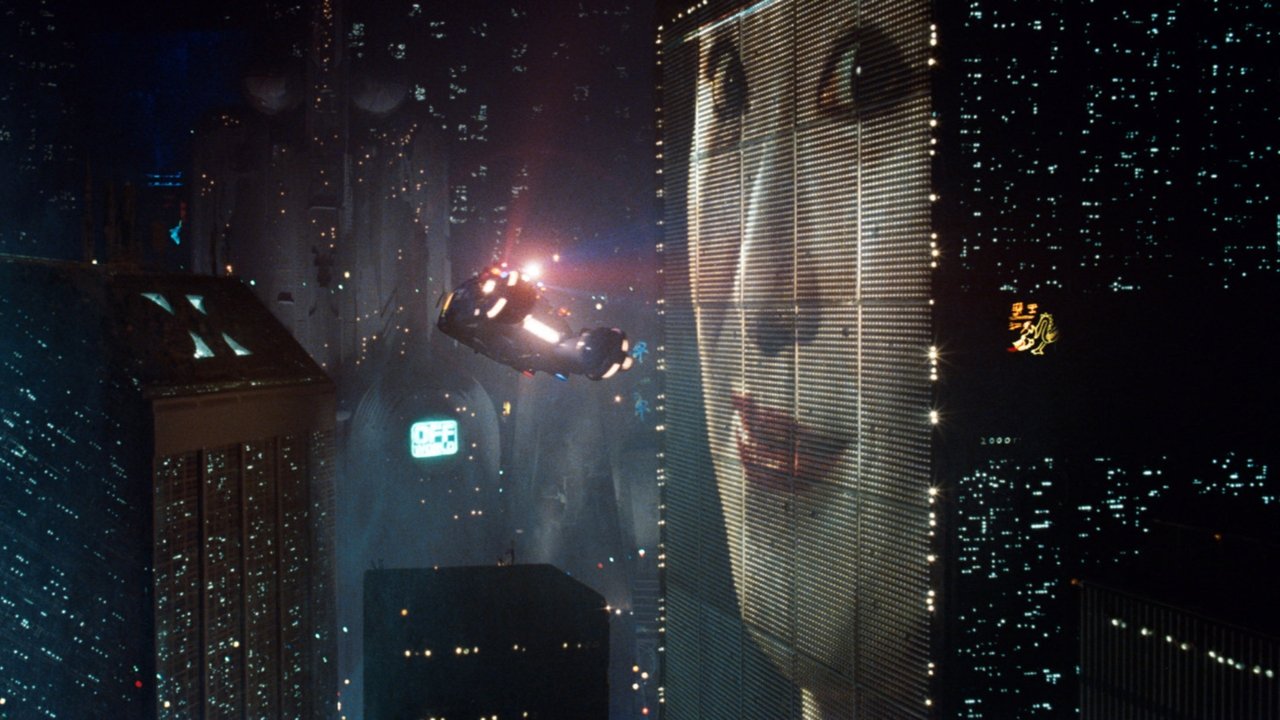

The look of Blade Runner is legendary, and rightly so. Its influence on dystopian visuals in cinema is immeasurable. This wasn't achieved with sleek CGI, but through meticulous practical effects, stunning matte paintings, and incredibly detailed miniatures that gave the city a tangible, gritty reality. Visionary "visual futurist" Syd Mead contributed heavily to the design, blending architectural styles and layering technology onto urban decay. You can almost smell the street food, feel the damp chill. Combined with Vangelis's haunting electronic score – a synth-laden soundscape of melancholy and wonder – the atmosphere is total immersion. The production itself was notoriously difficult; tales of Ridley Scott's demanding perfectionism, long night shoots under artificial rain, and friction with Harrison Ford (who reportedly found the process grueling) are well-documented. Yet, perhaps that very tension bled onto the screen, contributing to the film's weary, existential mood. Budgeted at around $28 million, its initial box office return of roughly $33 million domestically was considered a disappointment, proving audiences in 1982 perhaps weren't quite ready for its bleak vision.

### The Ambiguity Machine

Watching Blade Runner on VHS often meant encountering one specific version – perhaps the original theatrical cut with its studio-imposed voiceover and happier ending, or maybe, if you were lucky later on, stumbling across the Director's Cut (1992) which restored Scott's darker, more ambiguous vision (and famously added the unicorn dream sequence). This ambiguity, particularly regarding Deckard's own nature – human or Replicant? – became part of the film's mystique. The grainy NTSC picture, the slightly muffled sound, somehow enhanced the noir feel, the sense that you were peering into a murky, uncertain future. It wasn't just a movie; it felt like a transmission from a possible tomorrow, leaving you with more questions than answers, especially late at night with only the hum of the VCR for company. It’s a testament to the source material, Philip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, which similarly plumbed the depths of identity and empathy.

---

Rating: 9.5/10

This score reflects Blade Runner's status as a near-perfect execution of atmospheric sci-fi noir. Its groundbreaking visuals remain influential, Vangelis's score is iconic, the performances (especially Hauer's) are unforgettable, and its philosophical questions about humanity, memory, and artificial life resonate deeper with each passing year. While the pacing might test some modern viewers, and the initial theatrical cut had its flaws, the film's power, particularly in its later, more definitive cuts, is undeniable. It achieves a level of thematic depth and visual poetry rarely seen in the genre.

Blade Runner wasn't just a product of the 80s; it transcended its era. It’s a film that rewards repeat viewings, revealing new layers with each journey back into its rain-soaked streets. It remains a haunting masterpiece, a dark mirror reflecting our own anxieties about technology, identity, and the fleeting nature of existence itself. A true gem from the VHS era that still feels chillingly relevant.