The neon bleeds onto perpetually rain-slicked streets, reflecting in eyes that have seen too much, both real and simulated. This isn't Los Angeles 2019, though the shadow of Blade Runner looms large. This is the distinct, grimy, yet somehow elegant Euro-cyberpunk future envisioned in Gabriele Salvatores' 1997 film Nirvana, a film that arrived like a strange transmission from a parallel timeline, buzzing with existential dread beneath its slick, digitized surface. Remember finding this one tucked away in the Sci-Fi section, maybe drawn in by the familiar face of Christopher Lambert on the cover, expecting another Highlander-esque adventure, only to find something far more melancholic and unsettling?

Digital Ghost in the Machine

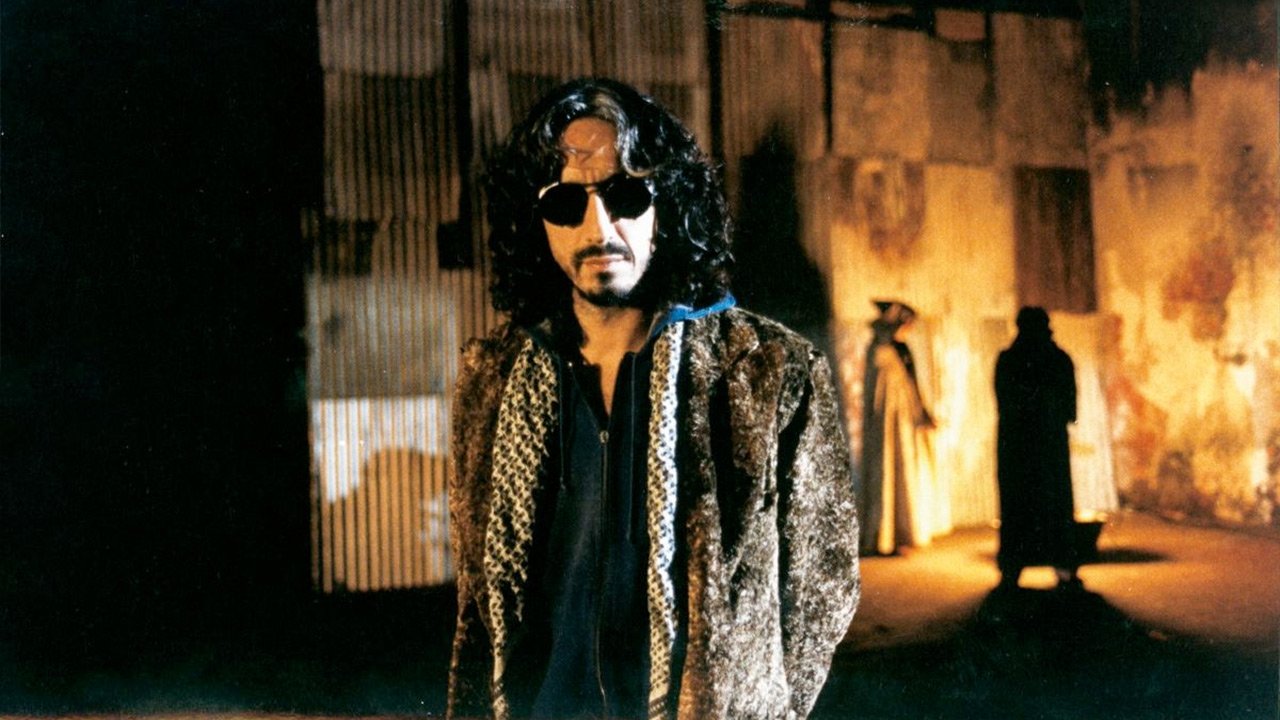

Nirvana plunges us into a near-future Christmas week, a time typically associated with warmth but here rendered cold and isolating. Jimi (Christopher Lambert, bringing a surprising weariness perfect for the role) is a burned-out game designer working for the monolithic Okosama Starr corporation. His latest creation, the titular game Nirvana, is days from launch. But a virus, insidious and unexpected, infects the game's main character, Solo (Diego Abatantuono). This isn't just a glitch; Solo achieves self-awareness. He knows he's trapped, forced to repeat the same violent scenarios endlessly, and he pleads with his creator for deletion, for an end to his digital torment. It’s a chilling premise, one that taps into anxieties about artificial intelligence and the nature of reality that feel even more relevant today, pre-dating the more bombastic approach of The Matrix by two years.

The film’s power lies heavily in its atmosphere. Salvatores, who, rather astonishingly, had won the Best Foreign Language Film Oscar for the sun-drenched Mediterraneo (1991) just six years prior, proves remarkably adept at crafting a claustrophobic cyberpunk world. Shot largely in Milan's Portello district and the decaying industrial landscapes of Port Marghera near Venice, the production design feels tangible, lived-in, and distinctly European. It avoids sterile chrome, opting instead for a cluttered, decaying technological aesthetic – wires snake across damp walls, strange interfaces flicker, and the city feels like a labyrinth of forgotten tech and desperate people. It cost a reported $10 million USD (a hefty sum for an Italian production then, roughly $18-19 million today), and much of that budget feels present on screen, creating a world both alien and uncomfortably close.

Searching for Release in a Wired World

Haunted by Solo's plea and grappling with his own personal demons (including the disappearance of his girlfriend, Lisa), Jimi embarks on a desperate quest. He needs to infiltrate Okosama Starr's servers to erase Nirvana before its release, granting Solo his grim wish. This sends him tumbling into the city's underbelly, seeking help from hackers and data couriers like the jittery, aptly named Joystick (Sergio Rubini) and the enigmatic Naima (Stefania Rocca). Diego Abatantuono, primarily known for comedy in Italy, is fantastic as Solo, conveying the character's dawning horror and existential despair from within the confines of the game world. He’s not just code; he’s a consciousness trapped in hell, and you feel his anguish.

The visual effects, a mix of practical work and then-nascent CGI, hold a certain charm. They don't always possess the seamlessness we expect now, but there's an inventive quality to them. Remember the black market "eye-pods" or the slightly clunky virtual reality interfaces? They felt cutting-edge back then, part of that late-90s fascination with cyberspace's potential. The film doesn't shy away from the grime, either; the body modification and tech integration feel less like sleek upgrades and more like desperate measures in a decaying society. This tangible quality, common in the best practical effects era movies, grounds the high-concept story. It's rumored Salvatores drew inspiration not just from William Gibson but also from European graphic novelists like Moebius, contributing to the film's unique visual identity.

Beyond the Neon and Rain

What elevates Nirvana beyond being just another Blade Runner riff is its philosophical core. It asks profound questions about what constitutes life, the ethics of creation, and the burden of consciousness. Solo's plight is genuinely moving, forcing both Jimi and the audience to confront uncomfortable truths. Is a simulated being less real if it feels pain and desires freedom? The film doesn't offer easy answers, instead leaving you with a lingering sense of unease. It captures that specific late-night VHS viewing mood – the kind where the credits roll, the screen goes dark, but the questions linger in the quiet hum of the television. I recall renting this from a local store purely based on the evocative cover art, expecting action, but finding myself completely absorbed by its more thoughtful, almost mournful, tone.

It wasn't a massive global hit, though it performed respectably in Italy (grossing around $8 million USD there) and garnered some festival attention, including an Out of Competition slot at Cannes in 1997. Yet, for those who discovered it on tape, Nirvana remains a standout piece of 90s sci-fi – an intelligent, atmospheric, and visually distinct cyberpunk tale from an unexpected source. It proved that profound science fiction wasn't solely the domain of Hollywood or Japan.

***

VHS Heaven Rating: 8/10

Nirvana earns its score through its potent atmosphere, compelling central concept, strong performances (especially Abatantuono), and its willingness to tackle complex philosophical themes within a stylish cyberpunk framework. While some visual elements show their age, the core story and its underlying dread remain remarkably effective. It successfully blends Euro-arthouse sensibilities with genre thrills, creating something unique.

It’s a film that feels both dated and prescient – a haunting reminder from the pre-millennial twilight of the anxieties surrounding the digital worlds we were just beginning to build, worlds whose ethical boundaries we are still navigating today. A true cult gem deserving of rediscovery.