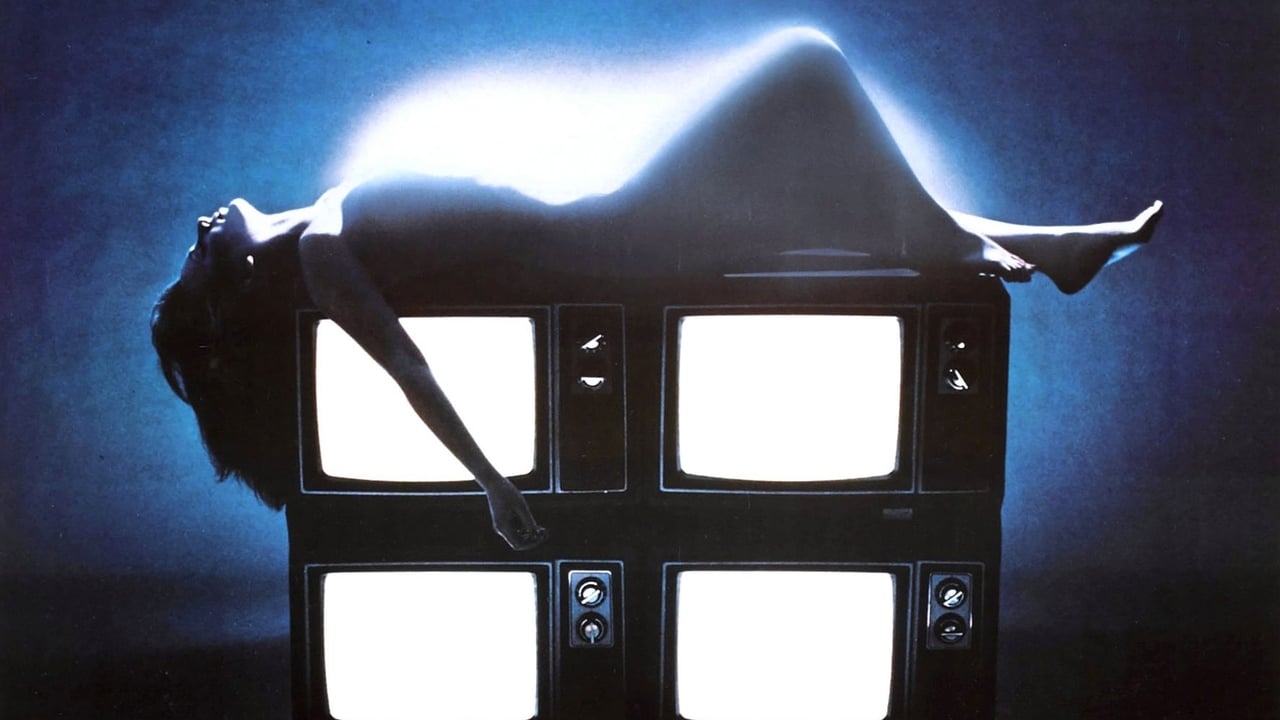

There's a cold, calculating gleam behind the promise of perfection, a digital ghost lurking just beneath the surface of manufactured beauty. Michael Crichton's 1981 sci-fi thriller Looker tapped into this unease long before deepfakes and algorithmic advertising became our daily reality. Forget jump scares; this is the slow-burn dread of technological overreach, wrapped in the glossy, detached aesthetic of early 80s corporate ambition. It captures a specific kind of paranoia, one that felt futuristic then but feels unnervingly familiar now.

The Scalpel and the Screen

We enter this world through the eyes of Dr. Larry Roberts (Albert Finney), a successful Beverly Hills plastic surgeon whose meticulously crafted world starts to fray when his model patients begin dying under mysterious circumstances. These aren't just any models; they're women seeking impossibly precise, mathematically defined 'perfection' – measurements provided, chillingly, by a shadowy tech corporation called Digital Matrix, run by the impeccably suave and utterly ruthless John Reston (James Coburn, radiating effortless menace). Roberts, initially baffled, soon finds himself pulled into a conspiracy involving subliminal advertising, corporate espionage, and technology far beyond mere surgical enhancement. Finney, an actor of considerable weight known for dramas like Murder on the Orient Express, brings a relatable, grounded confusion to Roberts, making him an effective everyman caught in a high-tech nightmare.

Pixel Perfect Terror

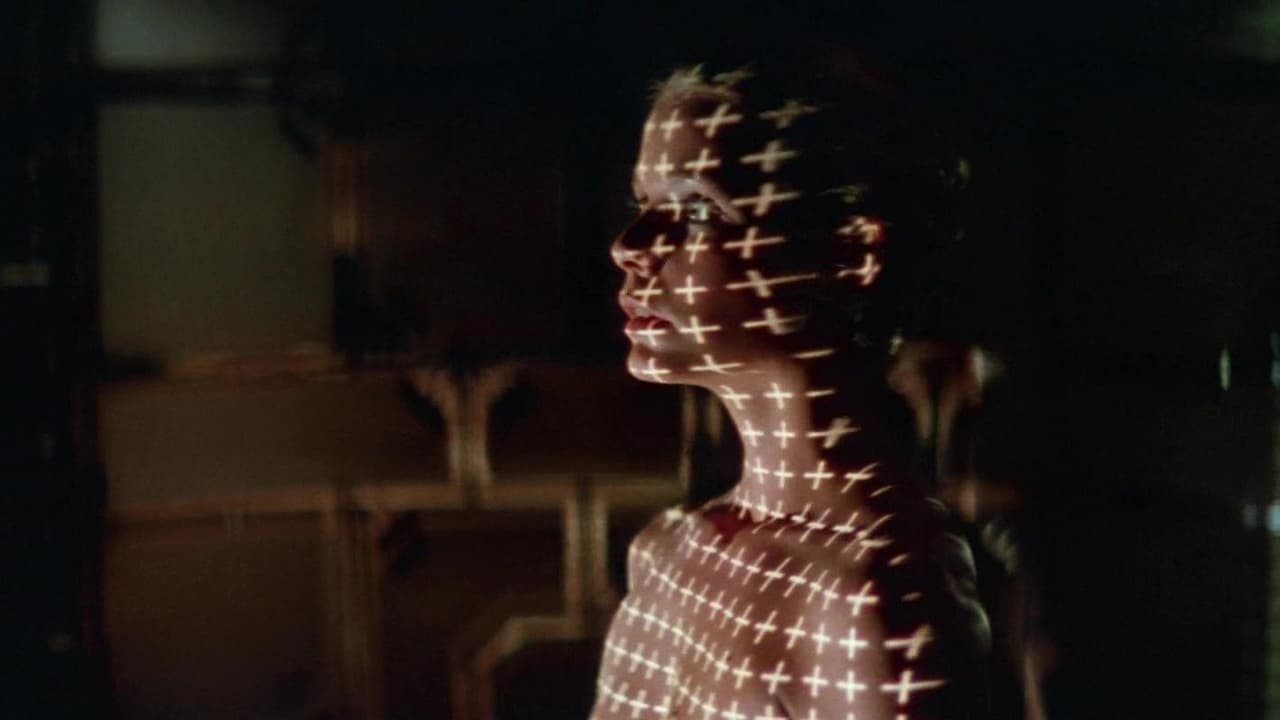

Looker is perhaps most famous, or infamous depending on your perspective, for its groundbreaking use of computer-generated imagery. Digital Matrix isn't just selling products; they're creating perfectly digitized versions of models for commercials, capable of hypnotic influence. The film features the first realistically shaded 3D CGI human character – a digital double of Cindy (Susan Dey, miles away from her Partridge Family persona). Created by the pioneering tech firm Information International, Inc. (Triple-I), this sequence was a painstaking technical feat in 1981. Watching it today, the effect is undeniably dated, yet it retains a strange, unsettling power. There's an emptiness in those early digital eyes, an uncanny valley quality that perfectly suits the film's themes of dehumanization. Didn't that primitive CGI feel both revolutionary and vaguely creepy back on a flickering CRT? Crichton, with his Harvard medical background and fascination with technology's dark potential (already explored in his novel The Andromeda Strain and his directorial debut Westworld), clearly saw where things were heading. He envisioned a future where images could be manipulated not just for entertainment, but for control.

Adding to the technological terror is the infamous "L.O.O.K.E.R." gun – Light Ocular-Oriented Kinetic Energetic Responsers. It doesn't kill, not directly. It fires pulses of light that induce a state of temporal suspension, making the victim lose seconds, even minutes, of time while appearing frozen to outsiders. It's a disorienting, insidious weapon, perfectly suited for a conspiracy built on unseen manipulation. The sequences where Roberts is targeted by this light pulse weapon effectively convey a sense of helplessness and paranoia – the world glitching around him, reality itself becoming unreliable.

Style Over Substance, But What Style!

Let's be honest, the plot mechanics sometimes feel a little thin, the character motivations occasionally murky. Looker was famously a box office disappointment, pulling in only about $3.3 million domestically against a reported $8-10 million budget (that's roughly $11 million earned against $34 million spent in today's money – a significant flop). Critics at the time often pointed to a script that didn’t quite live up to its intriguing premise. Yet, the film looks and feels distinct. The sleek, minimalist interiors of Digital Matrix, the cold precision of the technology, the sun-drenched but somehow sterile Los Angeles locations – it all contributes to an atmosphere of detached dread. Crichton directs with a cool, clinical eye, emphasizing the clean lines and reflective surfaces that hide a dark core. The score, too, adds to the unease, often favouring electronic pulses and unsettling ambiance over traditional orchestration. It's a film where the vibe is almost as important as the narrative. My own well-worn ex-rental tape certainly carried that specific mood through years of viewings.

The chase sequences, particularly one involving Roberts navigating a complex set during a commercial shoot while dodging assassins and the L.O.O.K.E.R. effect, are genuinely tense. There's a palpable sense of vulnerability, of being outmatched by forces you barely understand. It's this feeling, more than any specific plot twist, that lingers.

Legacy of the Look

Decades later, Looker feels remarkably prescient. Its anxieties about media manipulation, the impossible beauty standards amplified by technology, corporate surveillance, and the very nature of reality in a digitized world resonate perhaps even more strongly today. While its execution might be rooted in early 80s sensibilities (and technology), the core ideas were way ahead of the curve. It’s a fascinating snapshot of techno-paranoia just as the digital revolution was truly beginning to dawn. For fans of 80s sci-fi thrillers, it remains a compelling, if flawed, piece of the puzzle – a film whose ideas outpaced its immediate reception.

VHS Heaven Rating: 7/10

Looker earns its 7 for sheer atmospheric conviction, its chillingly predictive themes, and its status as a pioneering (if primitive) work of cinematic CGI. Finney and Coburn deliver solid performances, and Crichton's direction creates a palpable sense of high-tech dread. It loses points for a somewhat underdeveloped script and occasionally clunky pacing, preventing it from reaching classic status. However, its ambition and unsettling vision were notable for 1981 and have only gained relevance over time.

It's a film that reminds us that the screen looking back at us might see more than we think, a chilling thought solidified on grainy videotape long before the age of smart devices.