There’s a certain kind of cold dread that settles in the pit of your stomach when watching The Abyss. It’s not just the crushing pressure of the deep ocean, thousands of feet below the surface where sunlight is a forgotten memory. It’s the pressure cooker of human fear, paranoia, and frayed nerves trapped in a tin can at the bottom of the world, facing something utterly unknown. Watching it again, decades later, that feeling hasn’t diminished; if anything, the stories surrounding its creation only amplify the palpable tension bleeding through the screen.

Down Into the Dark

When a US nuclear submarine mysteriously sinks near the Cayman Trough, a nearby civilian underwater drilling platform, the Deep Core, is commandeered by Navy SEALs to assist in a rescue and recovery mission. Led by foreman Virgil "Bud" Brigman (Ed Harris), the roughneck crew, including Bud's estranged wife and rig designer Dr. Lindsey Brigman (Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio), finds themselves working alongside the tightly wound SEAL team, commanded by Lt. Hiram Coffey (Michael Biehn). As a hurricane rages above, cutting them off, and equipment begins to fail under the immense pressure, they discover they are not alone down there. Something luminous and intelligent watches from the abyss.

Cameron's Underwater Obsession

You can’t talk about The Abyss without talking about its legendary, almost mythical production. James Cameron, already riding high from Aliens and The Terminator, pushed himself, his crew, and his actors to the absolute limit. The film wasn't shot in the ocean, but primarily in two enormous, unfinished concrete cooling tanks at the abandoned Cherokee Nuclear Power Plant in Gaffney, South Carolina. Holding 7.5 million and 2.5 million gallons respectively, these became Cameron’s controlled underwater world, filled with chlorinated water so murky that visibility was often measured in feet. Stories from the set are notorious: grueling 70-hour weeks, constant submersion, technical nightmares, oxygen deprivation, and the sheer physical and mental toll on everyone involved. It sounds less like filmmaking and more like a deep-sea survival exercise. The reported $43-47 million budget (around $100 million today) ballooned, partly due to these insane logistical challenges.

Performances Forged in Pressure

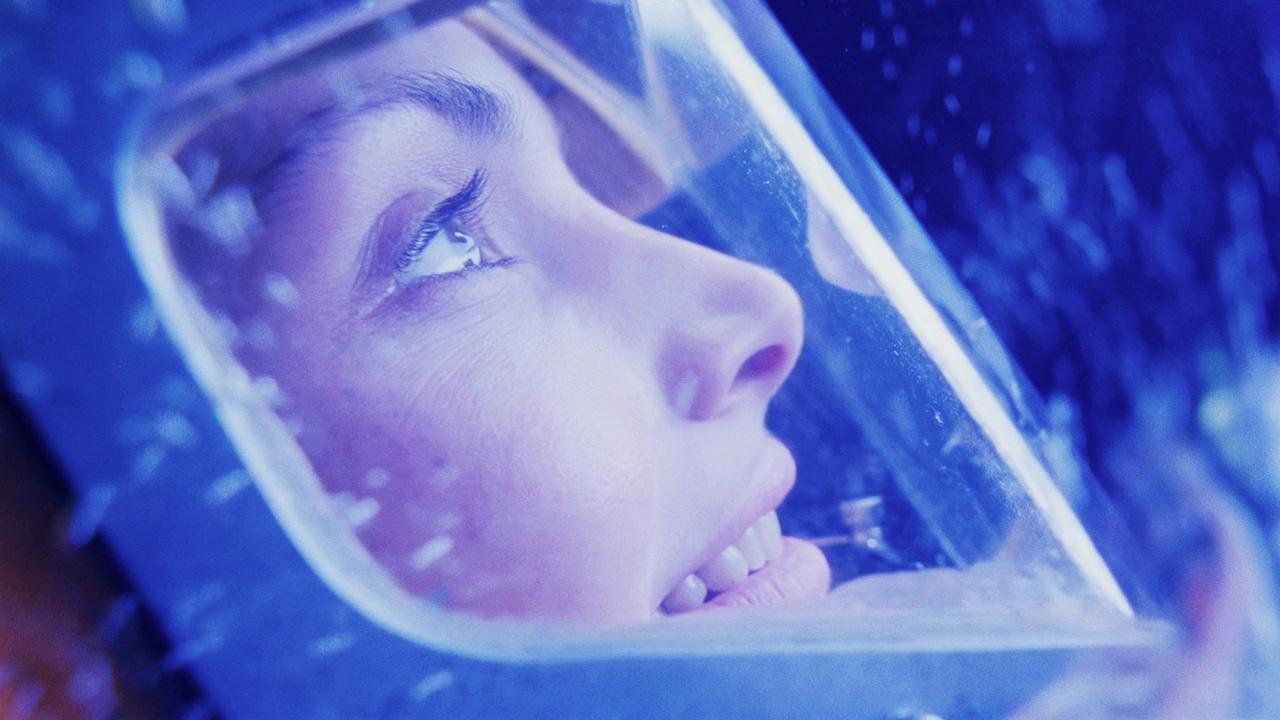

The strain is etched onto the actors' faces, and it translates into raw, authentic performances. Ed Harris as Bud is the weary heart of the film, a blue-collar guy trying to keep his crew safe and sane amidst escalating chaos. His reported near-drowning during the infamous liquid breathing sequence (a real, albeit experimental, technology using oxygenated fluorocarbon liquid) wasn't faked distress; Harris genuinely thought he was going to die and reportedly broke down weeping afterward, later allegedly punching Cameron. That intensity feels real on screen. Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio as Lindsey provides the sharp, scientific counterpoint, fiercely intelligent but equally pushed to her limits – her own on-set emotional breaking point is another well-documented piece of the film’s difficult lore. And Michael Biehn, a Cameron regular, is terrifying as Coffey, whose paranoia escalates due to High-Pressure Nervous Syndrome (HPNS), turning him into the film's human antagonist. Biehn’s performance is a chilling portrait of sanity fracturing under extreme duress, amplified by the claustrophobic, waterlogged environment. Doesn't his descent still feel unnervingly plausible?

Groundbreaking Sights, Enduring Atmosphere

For all the production hell, The Abyss delivered visuals that were simply staggering in 1989. The practical effects – the detailed submersible models, the vast Deep Core set, the eerie beauty of the Non-Terrestrial Intelligences (NTIs) – are phenomenal. They possess a weight and texture that holds up remarkably well. Alan Silvestri's score is a key component, mixing awe-inspiring, almost cathedral-like themes for the NTIs with throbbing, suspenseful cues that ratchet up the tension. And then there’s that scene: the water pseudopod. Created by ILM, this sequence, where seawater mimics Lindsey’s face, was a landmark moment in CGI history. Watching it on VHS back in the day, even through scanlines on a CRT, felt like witnessing pure movie magic, a glimpse into the future of filmmaking. Sure, CGI has evolved exponentially, but the artistry and impact of that moment remain undeniable.

The Tale of Two Endings

No discussion of The Abyss is complete without mentioning the two versions. The 1989 theatrical cut felt somewhat abrupt, hinting at a larger purpose for the NTIs but concluding rather quickly after the immediate human drama resolved. Studio pressure and runtime concerns led to significant cuts. However, the 1992 Special Edition restored nearly 30 minutes of footage, crucially including the subplot involving the NTIs' concern about humanity's self-destructive path, culminating in the threat of colossal tidal waves held back as a warning. This version deepens the film's themes, transforming it from a tense underwater thriller with sci-fi elements into a more profound, cautionary tale about humanity's place in the universe. For many fans, myself included, the Special Edition is the definitive Abyss. It feels like the story Cameron intended to tell.

Still Plumbing the Depths

The Abyss stands as a testament to James Cameron's singular vision and borderline obsessive drive. It's a film born of incredible difficulty, a technical marvel that pushed the boundaries of what was possible. The performances are raw, the atmosphere is thick with tension and wonder, and the underwater world feels both beautiful and terrifyingly hostile. While the theatrical cut might feel slightly incomplete, the Special Edition elevates it to a true sci-fi epic with a potent message. It perfectly captured that late-80s blend of Cold War paranoia and burgeoning digital wonder. Watching it today still evokes that sense of claustrophobia, that awe at the unknown lurking in the crushing blackness.

VHS Heaven Rating: 9/10 (Based on the Special Edition)

The score reflects the film's staggering technical achievements for its time, the intense performances born from real adversity, the masterful creation of atmosphere, and the enduring power of its core story, especially in its complete form. It loses a point perhaps for the pacing challenges inherent in its length and the slightly less impactful theatrical cut that many first experienced. It remains a monumental piece of 80s science fiction, a deep dive into fear, wonder, and the very pressures that define us.