There's a particular kind of dread that doesn't creep on shadowed feet, but rather bursts forth, wild-eyed and clumsy, from the undergrowth. It’s the feeling evoked by Don't Go in the Woods (1981), a film less meticulously crafted horror machine and more like a barely contained explosion in a backwoods exploitation factory. Watching it feels like unearthing a forbidden object, a grainy NTSC nightmare smuggled out of some forgotten corner of the video store, promising transgression but delivering something far stranger.

A Wrong Turn in the Wilderness

The premise is archetypal slasher fodder: four backpackers (Jack McClelland, Mary Gail Artz, James P. Hayden, Angie Brown) venture into the Utah mountains for what should be an idyllic escape. Predictably, their trip curdles into terror as they stumble into the domain of a hulking, feral mountain man armed with a crude spear/machete hybrid and an indiscriminate lust for slaughter. What sets Don't Go in the Woods apart isn't narrative ingenuity – far from it – but its sheer, almost hallucinatory commitment to relentless, nonsensical violence perpetrated by a killer who looks less like a terrifying monster and more like a disoriented lumberjack who wandered off set.

Director James Bryan, working with a budget rumored to be as low as $10,000-$20,000 (a pittance even in 1981, maybe $30-$60k today), essentially took his cast and crew – largely composed of friends, students, and locals – into the actual Utah wilderness and staged a series of increasingly bizarre murder vignettes. The film unfolds less like a story and more like a highlight reel of mayhem, loosely connected by scenes of our protagonists wandering aimlessly, delivering dialogue with the wooden conviction of a high school play performed under duress.

Chaos Captured on Camera

Forget carefully constructed suspense; Don't Go in the Woods operates on a principle of chaotic accumulation. People wander into frame, get dispatched in messy, often baffling ways, and then we cut back to our main group, largely oblivious. The editing is abrupt, the pacing lurches unpredictably, and the infamous sound design – a result of the film being shot largely silent and dubbed in post-production – lends everything an uncanny, disconnected quality. Footsteps crunch too loudly, screams echo unnaturally, and the ambient noise often feels completely detached from the visuals, adding another layer to the film's surreal texture.

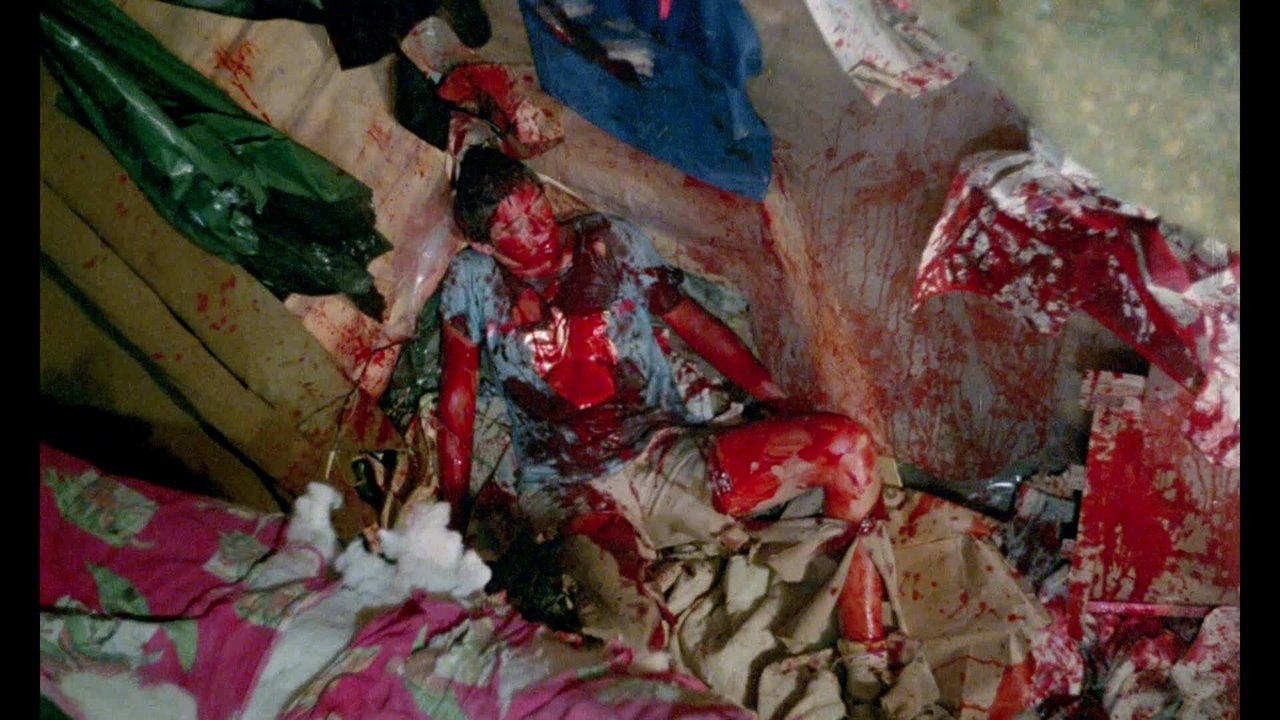

The practical effects are, charitably, rudimentary. Gallons of bright red stage blood are splashed with abandon, limbs are hacked with unconvincing thuds, and the gore feels less visceral horror and more messy performance art. Yet, there's an undeniable, grubby charm to its very cheapness. This wasn't polished Hollywood horror; this felt like something genuinely dangerous could have happened during filming. Stories abound of the guerilla nature of the shoot – battling weather, improvising scenes, and generally embracing the chaos. It’s this palpable sense of barely controlled filmmaking that gives the movie its weird energy. Remember that infamous wheelchair scene? Utterly gratuitous, logically nonsensical, yet somehow unforgettable in its brazen absurdity. Doesn't that moment perfectly encapsulate the film's bizarre appeal?

Accidental Artistry?

The performances are uniformly amateurish, but this somehow works in the film's favor. The line readings are stilted, the reactions often bafflingly inappropriate, yet it contributes to the overall dreamlike (or nightmare-like) quality. These don't feel like actors playing characters; they feel like real people awkwardly thrust into a terrifying, nonsensical situation, unsure of how to react – which, perhaps unintentionally, mirrors how an audience member might feel watching it. There’s a strange authenticity born from the lack of polish.

Perhaps the most famous aspect of Don't Go in the Woods is its inclusion on the UK's notorious "Video Nasties" list in the early 80s. Alongside genuinely disturbing films like Cannibal Holocaust (1980) and The Evil Dead (1981), its presence feels almost comical. While undeniably violent and crude, it lacks the mean-spirited nihilism or graphic intensity of many others on the list. Its banning likely had more to do with its lurid, effective poster art and title than its actual content, inadvertently cementing its cult status. It became forbidden fruit, whispered about in playgrounds and sought after by collectors drawn to its reputation. Finding this tape on a shelf felt like discovering contraband.

Legacy of the Low Budget

Don't Go in the Woods isn't a "good" film by any conventional metric. The acting is wooden, the script is threadbare, the direction is haphazard, and the effects are laughable. Yet... it endures. It's a prime example of the "so bad it's good" phenomenon, but even that feels slightly insufficient. It possesses a unique, almost outsider-art quality. It’s a testament to the drive to simply make a movie, regardless of resources or technical finesse. It captures a specific moment in low-budget, regional horror filmmaking that feels utterly alien to today's slick productions. For VHS hunters and connoisseurs of cinematic oddities, it remains a fascinating, often hilarious, and strangely compelling artifact.

Rating: 3/10

This score isn't for technical merit or storytelling prowess, which are minimal. It's a rating that acknowledges its historical notoriety as a Video Nasty, its status as a beloved "so bad it's good" cult classic, and the sheer, unhinged, accidental entertainment value derived from its profound ineptitude. It’s a train wreck you can’t look away from, rendered in glorious, grainy VHS fuzz.

Final Thought: In the pantheon of backwoods slashers, Don't Go in the Woods stands alone – not as a peak, but as a bizarre, blood-soaked gully, fascinating precisely because of how rough and uneven it is. It’s a mandatory watch for anyone exploring the weirdest corners of 80s horror video rentals.