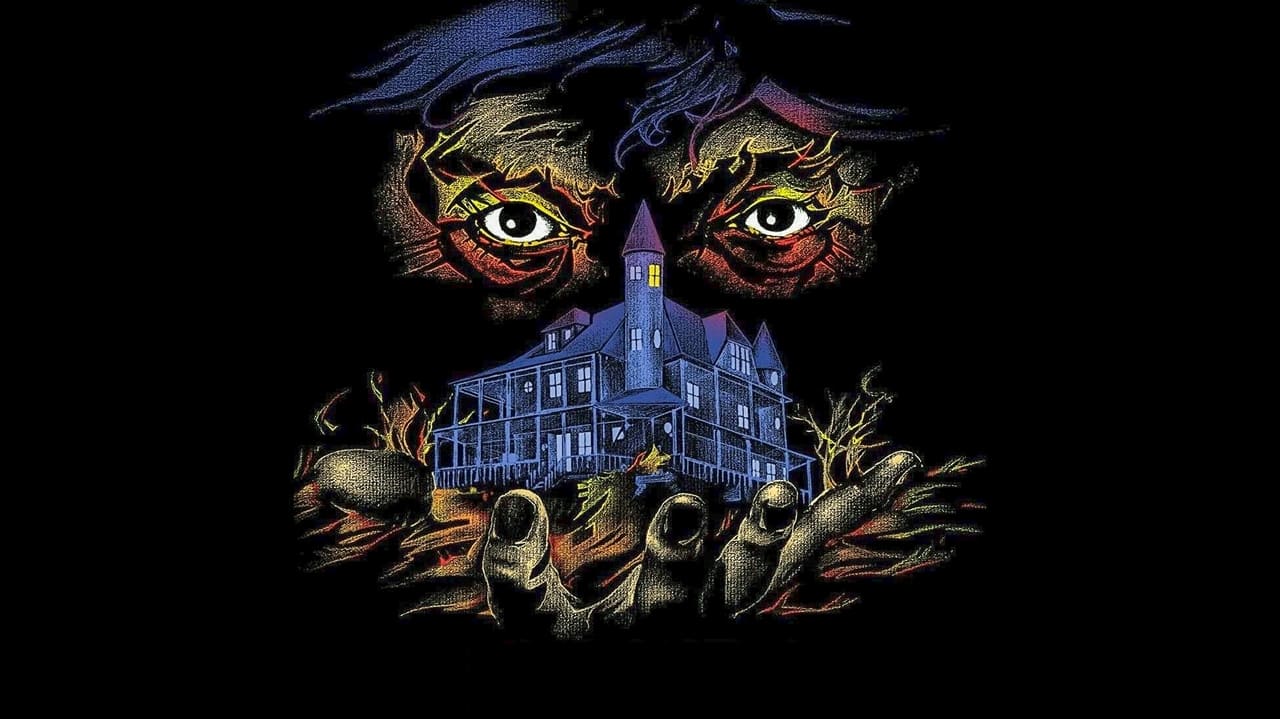

The very title whispers a primal warning, doesn't it? Don't Go in the House. It's less an invitation, more a stark command echoing from a scratched, rented cassette case, promising something genuinely unpleasant lurking behind a nondescript door. Released in 1979 but truly finding its grimy soul on countless worn-out VHS tapes throughout the early 80s, this film isn't about jump scares. It’s about the slow, suffocating descent into madness, fire, and the echoing trauma of abuse. It’s the kind of movie that leaves a greasy residue on your mind long after the tracking lines fade.

A House of Horrors, Both Real and Imagined

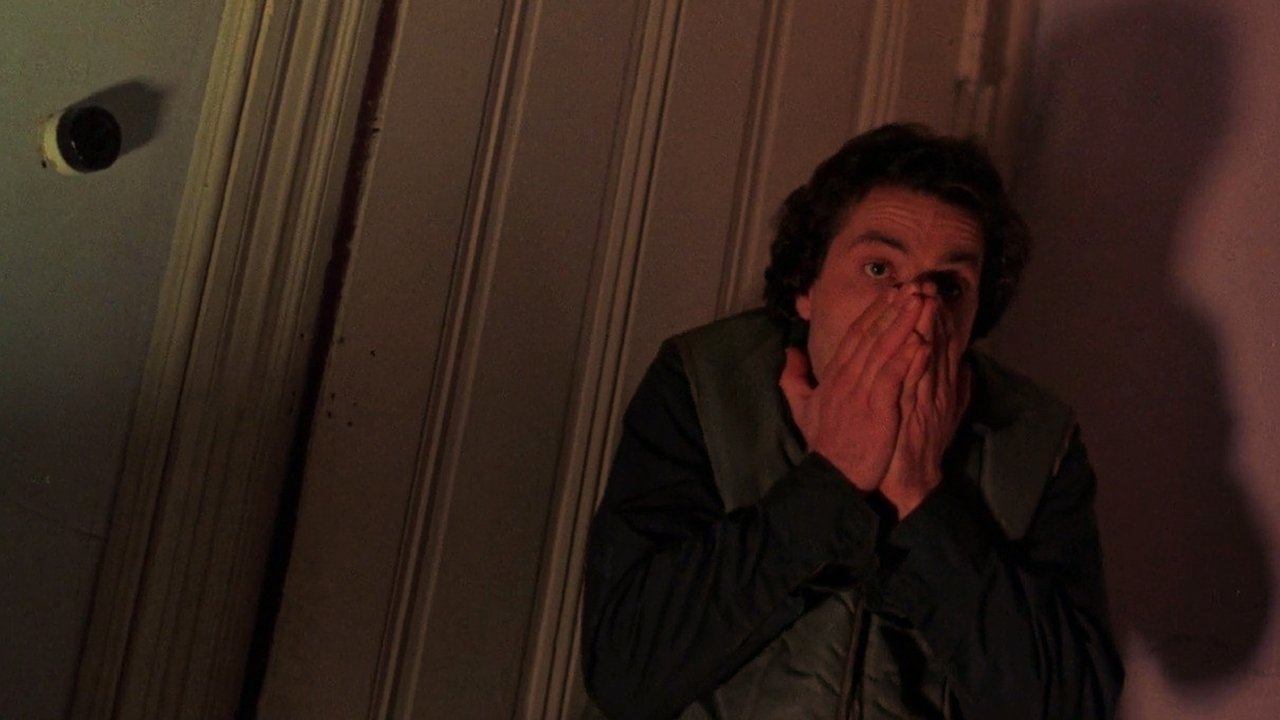

Our guide into the darkness is Donald 'Donny' Kohler, brought to unnerving life by Dan Grimaldi in a performance that chills long before his memorable turn as Patsy Parisi on The Sopranos. Donny works a thankless job at an incinerator plant, surrounded by fire, returning each night to a gothic, decaying house dominated by his cruel, abusive mother. When she finally dies, the years of torment don't just evaporate; they curdle. Donny snaps, and the voices in his head, echoes of his mother's abuse, start demanding retribution... using the very element that defined his childhood suffering: fire.

The film doesn't shy away from its grim premise. Donny, believing he can burn the "evil" out of women, begins luring them back to his home. What follows cemented Don't Go in the House's reputation, particularly landing it squarely on the infamous UK "Video Nasties" list. The scenes where Donny, clad in a disturbingly makeshift flame-retardant suit, unleashes his fury with a flamethrower in a specially constructed steel room are genuinely harrowing.

Forged in Fire: The Practical Horrors

Forget CGI polish; this is raw, practical effects horror that feels dangerously real. Director Joseph Ellison, who also co-wrote the screenplay (reportedly inspired by a horrifyingly true news story), pushed the boundaries for the meager budget (estimated around $150,000, which even in '79 was peanuts). There are stories, dark legends perhaps, surrounding the filming of these sequences. Grimaldi himself wore an asbestos-lined suit – a detail that screams of a bygone, less safety-conscious era of filmmaking. The first actress subjected to the flame room, Johanna Brushay, was apparently terrified during the filming, adding a layer of uncomfortable verisimilitude to her character's plight. Ellison captured a raw, terrifying spectacle that relies on the inherent fear of fire, not elaborate trickery. Doesn't that primal fear still hit hard, even knowing it's 'just a movie'?

Adding to the oppressive atmosphere is the location itself. Much of the film was shot inside the imposing Strauss Mansion in Atlantic Highlands, New Jersey – a place already steeped in local lore and ghost stories. You can feel the history, the decay, the sheer weight of the past pressing down on Donny, amplifying his isolation and descent. The house isn't just a setting; it's practically a character, a mausoleum holding decades of pain.

Beyond the Flames: A Damaged Psyche

While undeniably an exploitation film, Don't Go in the House reaches for something slightly deeper than mere shock value. Grimaldi's performance is key here. He portrays Donny not as a monstrous caricature, but as a profoundly broken man-child, haunted by auditory hallucinations and trapped in a cycle of trauma. His fumbling attempts at normalcy outside the house contrast sharply with the methodical horror within, making his eventual breakdown feel disturbingly inevitable. It shares DNA with other bleak character studies of the era, like William Lustig's Maniac (1980), focusing intensely on the disturbed psychology of its killer.

The score by Richard Einhorn (Shock Waves, Deadly Eyes) complements the visuals perfectly, weaving a tapestry of dread and melancholy that underscores Donny's warped reality. It’s not bombastic; it’s insidious, creeping under your skin alongside the film's grimy visuals and claustrophobic interiors. This wasn't a slick Hollywood production; it feels raw, almost documentary-like in its depiction of squalor and mental collapse, a hallmark of many 70s horror cult classics discovered on home video.

Lingering Embers

Don't Go in the House is not an easy watch. It's bleak, it's nasty, and its low-budget origins are apparent in the sometimes uneven pacing and supporting performances. Yet, its power to disturb remains potent. It taps into fundamental fears – abuse, isolation, madness, and the terrifying destructive power of fire. Finding this on a dusty video store shelf felt like unearthing forbidden knowledge, something truly transgressive that wasn't meant for polite company. My own taped-off-late-night-TV copy, complete with static bursts, felt like contraband.

It may lack the iconic status of some of its contemporaries, but for those who stumbled upon it during the golden age of VHS, its grim atmosphere and genuinely shocking sequences left a scar. It’s a reminder of a time when horror felt truly dangerous and unpredictable.

Rating: 6/10

Justification: The film scores points for its genuinely unsettling atmosphere, Dan Grimaldi's committed central performance, and the raw, unforgettable horror of its practical fire effects, which remain disturbing even today. Its place as a notorious "Video Nasty" adds to its cult legacy. However, it loses points for uneven pacing, some weaker supporting elements typical of its low budget, and its ultimately repetitive structure in the second half. It's grimly effective but undeniably rough around the edges.

Final Thought: More than just an exploitation flick, Don't Go in the House is a grimy, disturbing plunge into psychological hell, powered by practical effects horror that feels perilously real. A bleak reminder from the VHS shelves that some doors are best left unopened.