Okay, pull up a worn armchair, maybe pour yourself something strong. We're not diving into explosions or high-school hijinks today. Instead, let's talk about a film that likely sat on a dustier shelf in the video store, perhaps in the 'Foreign' or 'Director Spotlight' section, radiating an intensity that felt worlds away from the neon glow of the main aisles: Werner Herzog's 1979 adaptation of Woyzeck. Finding this tape often felt like unearthing something raw, something potentially unsettling, and you weren't wrong.

### A Cry from the Abyss

What immediately strikes you, watching Woyzeck even now, is its suffocating sense of inevitability. Based on the fragmented, unfinished 19th-century play by Georg Büchner – itself a revolutionary piece depicting the plight of the common man – Herzog’s film plunges us directly into the tormented world of Franz Woyzeck. He’s a lowly soldier in a provincial German town, subjected to the petty cruelties of his superiors and the bizarre, dehumanizing experiments of a local doctor (who pays him pennies to subsist solely on peas, observing his physical and mental decay). This isn't a story of suspense in the traditional sense; it's a chronicle of a man’s unraveling, a slow-motion descent into a hell created by poverty, humiliation, and betrayal.

### The Herzog-Kinski Crucible

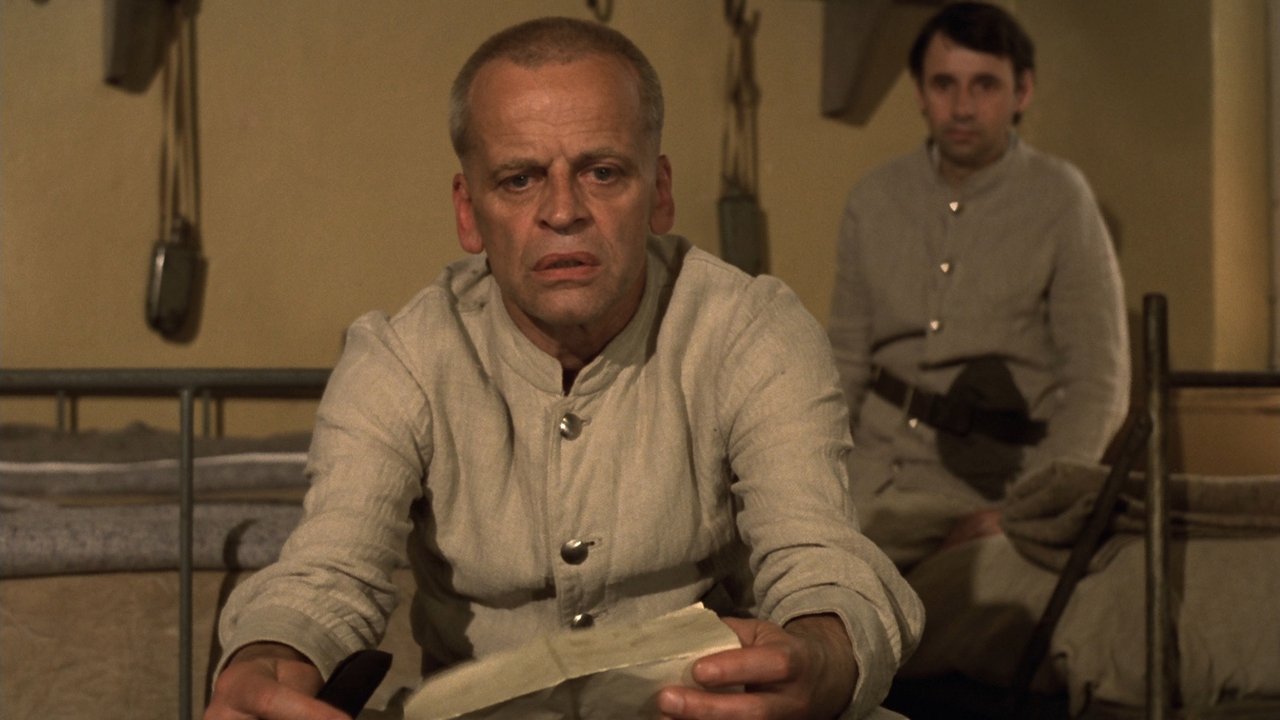

At the heart of this harrowing journey is Klaus Kinski. Fresh off the physically and emotionally draining production of Herzog's Nosferatu the Vampyre (famously, Woyzeck began shooting a mere five days after Nosferatu wrapped, utilizing the same exhausted star and crew), Kinski embodies Woyzeck with a terrifying fragility. This isn't the explosive rage we often associate with Kinski; it's an implosive performance. His Woyzeck shuffles, twitches, his eyes wide with a confusion that slowly curdles into paranoid certainty. We see the weight of the world pressing down on him, the casual disregard of the Captain (Wolfgang Reichmann, perfectly embodying pompous indifference) and the clinical cruelty of the Doctor (Willy Semmelrogge) chipping away at his sanity. Kinski makes Woyzeck's suffering palpable, a raw nerve exposed to the audience. It’s a performance that burrows under your skin, deeply uncomfortable yet utterly mesmerizing. Knowing that Herzog harnessed this intensity mere days after Kinski had endured hours in the Nosferatu makeup adds another layer to the sheer force of will captured on screen.

### Marie's Burden, Mattes' Triumph

Opposite Kinski is Eva Mattes as Marie, Woyzeck’s common-law wife and the mother of his child. Mattes delivers a performance of profound weariness and quiet desperation. Her Marie isn't simply an adulteress; she’s a woman trapped by circumstance, yearning for a splash of color (represented by the charismatic Drum Major, played with swagger by Josef Bierbichler) in her bleak existence. Her eventual betrayal of Woyzeck feels less like malice and more like a gasp for air in a suffocating environment. Mattes won Best Supporting Actress at the Cannes Film Festival for this role, and it’s easy to see why. She provides the essential human counterpoint to Woyzeck's spiraling madness. It’s a performance made even more remarkable by the fact, revealed later, that Mattes was pregnant during the demanding shoot.

### Austere Beauty, Unflinching Gaze

Herzog’s direction is as stark and deliberate as the story itself. Shot primarily in the preserved historical town of Telč in what was then Czechoslovakia, the film has a muted, earthy palette. The camera often remains static, observing scenes with an almost clinical detachment that mirrors the Doctor's experiments. Yet, within this austerity, Herzog finds moments of haunting beauty – the mist rolling over the landscape, the stark compositions that isolate Woyzeck against the uncaring world. The production was famously achieved on a shoestring budget (reportedly under $500,000) and shot with incredible speed – some accounts say 18 days with editing completed in just four. This sense of urgency, born perhaps of necessity, translates into the film’s raw, unpolished feel, perfectly complementing the source material's fragmented nature. There are no flashy effects here, just the brutal landscape and the expressive agony etched on Kinski's face.

### A Relic of Unease

Watching Woyzeck on VHS, likely on a fuzzy CRT screen, felt different from watching, say, Commando. There was no easy catharsis, no triumphant heroics. It was the kind of film you rented when you were perhaps feeling a bit more introspective, curious about the capabilities of cinema beyond pure entertainment. It’s a film that asks difficult questions: What happens when society grinds a person down? Where does responsibility lie when poverty and humiliation breed violence? Does the starkness of Woyzeck's plight still echo in the forgotten corners of our own world? It certainly wasn't feel-good viewing, but encountering it felt significant – a brush with something potent and artistically uncompromising. It stands as a testament to Herzog's unique vision and his unparalleled ability to draw performances of almost unbearable intensity from his actors, particularly the singular force that was Klaus Kinski.

---

Rating: 8.5/10

Justification: While undeniably bleak and demanding, Woyzeck is a masterful piece of filmmaking. Herzog's direction is precise and atmospheric, capturing the essence of Büchner's work with stark power. Kinski delivers one of his most harrowing and controlled performances, perfectly complemented by Eva Mattes' award-winning turn. The film’s low-budget origins and rapid production only add to its raw, urgent energy. It loses a point and a half simply because its unrelenting despair makes it a difficult, rather than enjoyable, watch, limiting its appeal for casual viewing, even among seasoned cinephiles.

Final Thought: Woyzeck remains a chilling, unforgettable experience – a stark portrayal of dehumanization that lingers long after the tape hiss fades, reminding us of the darkness that can gather when empathy fails.