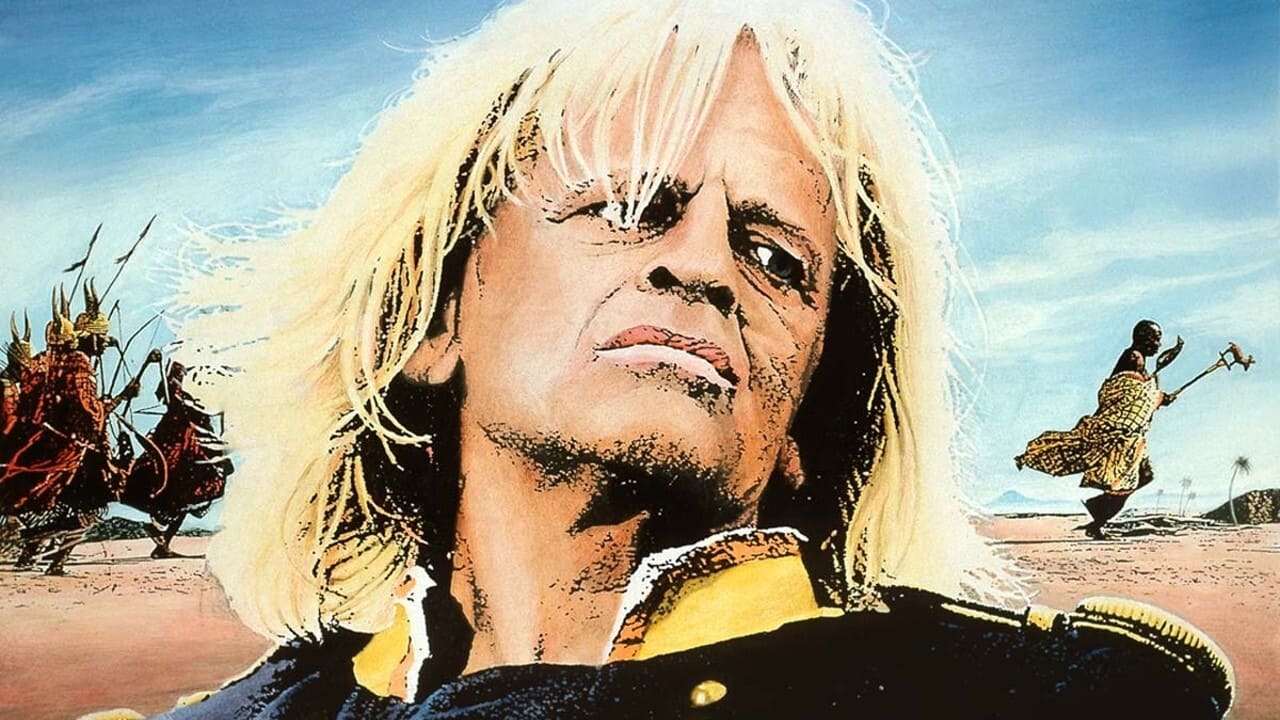

Okay, settle in, maybe dim the lights a bit. Let’s talk about a film that feels less like watching a movie and more like experiencing a fever dream captured on celluloid: Werner Herzog's Cobra Verde from 1987. There’s a certain weight that comes with pressing play on this one, isn't there? Especially knowing it represents the final, explosive collaboration between Herzog and the human tempest that was Klaus Kinski. It’s a film that doesn’t just flicker on the screen; it burns.

### A Descent into Sun-Scorched Madness

What strikes you first, perhaps, isn't the plot, but the overwhelming sensory assault. Herzog plunges us headfirst into the suffocating heat and moral decay of late 19th-century Brazil, then transports us across the Atlantic to the equally intense, complex world of the Kingdom of Dahomey in West Africa (modern-day Benin). We follow Francisco Manoel da Silva (Klaus Kinski), a feared bandit aptly nicknamed Cobra Verde, whose reputation for violence makes him useful, yet terrifying, to the plantation owners who employ him. In a move born of fear and cynical expediency, they dispatch him on what they assume is a suicide mission: sail to Africa and somehow revive the slave trade with the fearsome King Ghezo (King Ampaw).

The narrative, loosely adapted from Bruce Chatwin's novel The Viceroy of Ouidah, often feels secondary to the sheer spectacle and the oppressive atmosphere Herzog crafts. This isn't a straightforward historical drama; it’s Herzog filtering history through his unique lens of obsession, ambition, and the terrifying beauty of human folly against vast, indifferent landscapes. Remember watching this on a fuzzy CRT? The grain of the VHS tape almost seemed to merge with the dust and grit on screen, pulling you deeper into its hallucinatory world.

### The Eye of the Storm: Kinski's Final Fury

You simply cannot discuss Cobra Verde without confronting the supernova at its center: Klaus Kinski. As Francisco Manoel, he is less a character and more a force of nature – arrogant, desperate, magnetic, and utterly consumed by his own myth. His eyes, blazing with a terrifying intensity, seem to bore right through the screen. This wasn't just acting; it felt like watching Kinski channel something primal, volatile, perhaps even dangerous. Does his performance capture the desperation of a man cornered by his past and flung into an impossible future? Absolutely.

Of course, the legendary friction between Herzog and Kinski reached its zenith during this production, and knowing those stories inevitably colours the viewing experience. It’s almost impossible not to see the real-life chaos bleeding onto the screen. Filming in Ghana was plagued with difficulties; permits vanished, local chiefs demanded escalating payments, and Kinski, according to Herzog, unleashed tirades of abuse that terrorized the cast and crew. In a now-infamous incident, Kinski’s explosive rage led him to fire the original cinematographer, Thomas Mauch (who shot classics like Aguirre, the Wrath of God), forcing Herzog to hastily bring in Viktor Růžička mid-production. Herzog himself described the filming as existing under "a constant state of Kinski's terror." It's a testament to Herzog's almost insane perseverance that a coherent film emerged at all. Does this knowledge distract, or does it add a layer of disturbing authenticity to the madness depicted?

### Spectacle and Shadow

Herzog, ever the master of capturing stunning, often unsettling imagery, fills the screen with unforgettable moments. The sight of Da Silva training an army composed entirely of Dahomey women is striking, almost surreal. The vast landscapes, the intricate rituals, the sheer number of extras Herzog somehow marshalled – it all contributes to a sense of epic scale, achieved not with CGI, but with boots-on-the-ground logistical nightmares. Think about that scene where Kinski seems dwarfed by hundreds, possibly thousands, of Ghanaian extras during a ceremonial sequence – there's an authenticity there, a feeling of being truly present in a different time and place, that digital effects rarely replicate.

Yet, the film wrestles with difficult themes. It depicts the brutality of the slave trade and colonialism, but its perspective can feel ambiguous, almost observational rather than condemning. Da Silva is an exploiter, yet he's also portrayed as an outcast, a pawn thrust into circumstances beyond his control. The film doesn't offer easy answers or moral clarity. It presents a world steeped in violence and exploitation, leaving the viewer to grapple with the ugliness on display. What does it truly say about power, colonialism, or the individual's capacity for both creation and destruction?

### The End of an Era on Tape

Watching Cobra Verde today, especially if you first encountered it on a well-worn VHS tape perhaps rented from a store's slightly intimidating 'World Cinema' section, feels like unearthing a potent artifact. It’s raw, challenging, and undeniably flawed. The narrative sometimes stumbles, overshadowed by the visual grandeur and the sheer force of Kinski’s personality (and notoriety). It doesn't quite reach the sublime heights of Aguirre (1972) or the operatic ambition of Fitzcarraldo (1982), Herzog's earlier masterpieces with Kinski. Yet, as the final chapter in one of cinema's most fascinating and fraught director-actor relationships, it possesses a unique, almost tragic power.

Rating: 7/10

Justification: Cobra Verde is a visually stunning and atmospherically dense film, anchored by another unforgettable, if characteristically volcanic, performance from Klaus Kinski. Werner Herzog's ambition and eye for breathtaking imagery are undeniable. However, the narrative feels less focused than his best work, occasionally getting lost in the spectacle and the infamous behind-the-scenes turmoil which, while fascinating trivia, sometimes overshadows the story itself. The thematic exploration of colonialism and madness is potent but lacks the sharp clarity of earlier Herzog/Kinski collaborations. It earns a 7 for its sheer audacity, visual power, and its significant place as the turbulent conclusion to a legendary cinematic partnership, even if it doesn't quite reach masterpiece status.

Final Thought: What lingers most after the credits roll isn't necessarily the story, but the searing image of Kinski, a solitary figure raging against the waves on a desolate beach – a fitting epitaph, perhaps, for both the character and the explosive collaboration that defined an era of filmmaking.