### La Terrazza (1980)

The clinking of ice in glasses, the murmur of overlapping conversations under a Roman sky, the forced laughter that doesn’t quite reach the eyes – these are the first impressions offered by Ettore Scola’s La Terrazza. It isn't a party you necessarily want an invitation to, but one you can’t look away from. Released in 1980, this film feels less like a story being told and more like eavesdropping on the slow, collective sigh of a generation confronting the chasm between youthful ideals and the compromises of middle age. Watching it again, decades later, that sense of poignant observation feels sharper than ever.

A Gathering of Ghosts

The premise is deceptively simple: a group of friends, predominantly left-leaning intellectuals and artists, gather periodically on a luxurious Roman terrace. They eat, they drink, they posture, and, most importantly, they unravel. Scola, along with co-writers Age & Scarpelli (legends of Italian screenwriting), crafts a narrative mosaic. We don't follow a single plotline; instead, the film drifts, focusing vignette-style on different members of this privileged, yet profoundly unhappy, circle. The terrace itself becomes a stage for their existential crises, a gilded cage where political fervor has curdled into cynicism and creative passion has run dry.

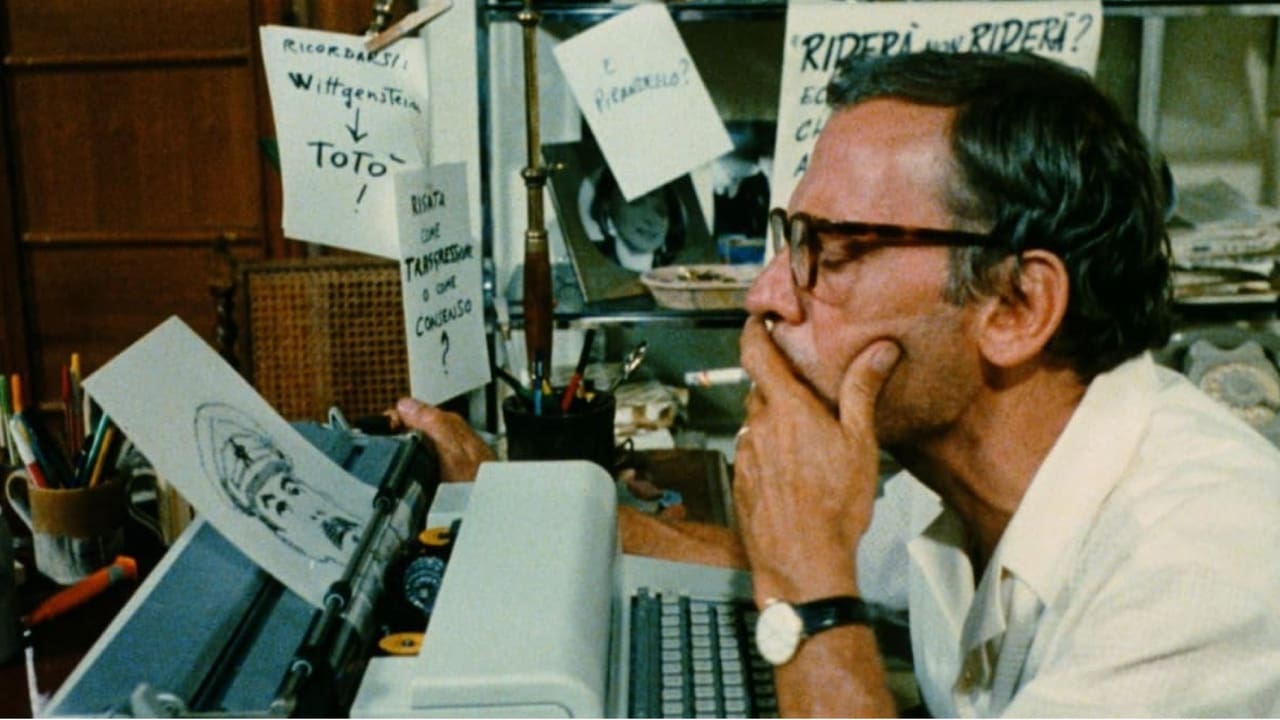

It's the faces looking out from that terrace that truly anchor the film. What an ensemble! We have Marcello Mastroianni as Luigi, a screenwriter blocked and bewildered, unable to reconcile his communist ideals with his comfortable life. There's Vittorio Gassman as Mario, a Communist Party deputy wrestling with impotence both political and personal. And Jean-Louis Trintignant portrays Enrico, a film producer whose professional anxieties mirror his decaying marriage. Each actor, already iconic figures in European cinema (think Mastroianni in 8½, Gassman in Il Sorpasso, Trintignant in The Conformist), brings a weary authenticity to their roles. They aren't just playing characters; they feel like they're embodying the very soul of Italian intellectual disillusionment at the turn of the decade.

Words as Weapons, Silence as Armor

This is a film built on talk – sharp, witty, bitter, and often devastatingly honest dialogue. The screenplay, which deservedly won Best Screenplay at the 1980 Cannes Film Festival (along with a Best Supporting Actress award for Carla Gravina), is the film's beating heart. It dissects the anxieties, hypocrisies, and regrets of these men (and the women observing them) with surgical precision. Scola, who so masterfully orchestrated complex human interactions in films like We All Loved Each Other So Much (1974) and later A Special Day (1977), allows conversations to ebb and flow naturally, sometimes overlapping into a cacophony of discontent, other times punctuated by uncomfortable silences that speak volumes.

There's a palpable sense of lives lived, of shared histories now viewed through the disappointing lens of the present. Did their youthful political fire change anything? Has their art made a difference, or just provided a comfortable living? These aren't questions asked overtly, but they hang heavy in the air, thick as the Roman humidity. It’s interesting to note that Scola and his writers were very much part of the generation and milieu they were depicting, adding another layer of self-reflection to the proceedings. It’s less a condemnation, perhaps, than a painful, public stock-taking.

Beyond the Blockbusters: A VHS Discovery

Let's be honest, La Terrazza probably wasn't the tape you grabbed on a Friday night hoping for car chases or creature features. It likely sat in the "Foreign Films" or "Drama" section of the video store, maybe with slightly intimidating cover art featuring those famous European faces looking suitably serious. Finding and renting something like this felt different – maybe a recommendation from the store clerk, maybe a curiosity sparked by a review in a newspaper discovered days later. It represented the other side of the VHS coin: the opportunity to step outside the mainstream, to engage with cinema that demanded more attention, that aimed for intellectual and emotional resonance over visceral thrills. Watching it felt like uncovering a hidden gem, a dispatch from a different world of filmmaking. My own faded memory involves finding it tucked away, deciding to take a chance, and being rewarded with something that stuck with me long after the credits rolled and the VCR whirred to a stop.

The film isn't without its challenges. Its episodic structure and deliberate pacing might test the patience of some viewers. The focus is almost entirely on the male characters' angst, although the female characters often serve as wry, perceptive observers of the unfolding melancholy. Yet, the cumulative effect is powerful. Scola doesn't offer easy answers or resolutions. He simply presents these characters, flaws and all, caught in the amber of their own discontent.

Rating: 8/10

La Terrazza earns its 8 not for pulse-pounding excitement, but for its fearless honesty, its masterful ensemble performances, and its sharp, enduring portrait of intellectual disillusionment. The writing is exceptional, capturing the specific anxieties of its time and place while touching on universal themes of aging, regret, and the compromise of ideals. It’s a demanding film, certainly, and its talkative nature and downbeat tone mean it won’t connect with everyone expecting typical 80s fare. However, for those willing to engage with its complex characters and Chekhovian atmosphere, it offers profound rewards and showcases European cinema giants working at the peak of their powers.

It leaves you pondering: What becomes of revolutionary spirit when the revolution fails to materialize, or worse, when its proponents simply get comfortable? La Terrazza doesn't shout its answers, but whispers them on the breeze drifting across that melancholic Roman rooftop.